A Community of Trees

Curated by: Emmy Meredith

Curatorial Advisors: Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan

Online Launch: March 1, 2024

Curatorial Advisors: Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan

Online Launch: March 1, 2024

A Community of Trees is a project that we hope can inspire a greater feeling of connection to others and to nature.

The desire behind this exhibition is to highlight the beauty and significance of trees and how this can be displayed through various art forms and mediums. Though it is not widespread knowledge, trees have the ability to communicate with each other through a variety of means. Their elaborate root systems contain fungi which can send messages to nearby connected trees to warn of dangers or other predators. Just as humans function best when working together as a collective and a community, trees are best able to thrive when they are a part of a forest, connected to other trees. Through this exhibition we hope to display works that highlight the versatility of trees and how they are an important and essential part of the ecosystem.

The desire behind this exhibition is to highlight the beauty and significance of trees and how this can be displayed through various art forms and mediums. Though it is not widespread knowledge, trees have the ability to communicate with each other through a variety of means. Their elaborate root systems contain fungi which can send messages to nearby connected trees to warn of dangers or other predators. Just as humans function best when working together as a collective and a community, trees are best able to thrive when they are a part of a forest, connected to other trees. Through this exhibition we hope to display works that highlight the versatility of trees and how they are an important and essential part of the ecosystem.

Tree of Peace: Community ProjectFrom the plaque at the base of the Tree of Peace:

On July 11th, 1991, a group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, gathered in solidarity at the London Peace Garden. They planted a White Pine Tree, one year after the Quebec Police, SQ, had fired upon Kanien'keha:ka women, men, and children at Kanehsata:ke, Quebec. The Mohawk people were attempting to protect their sacred land from the municipality of Oka development. The standoff lasted 78 days. The Great White Pine commemorates Peace, Power, and Righteousness amongst all people. It is a symbol of the Kaianera'ko:wa, the Great Law of Peace. Below the Tree are buried the weapons of war. Dan and Mary Lou Smoke were responsible for organizing this community project, which centered on the planting of the Tree of Peace.

|

Maria Awaraji

Leafy Situation started off as a combination between a photograph of my grandmother and a mosaic mandala.

I was inspired by how much nature is a cycle which nurtures our living.

I was inspired by how much nature is a cycle which nurtures our living.

Leafy Situation, 2021

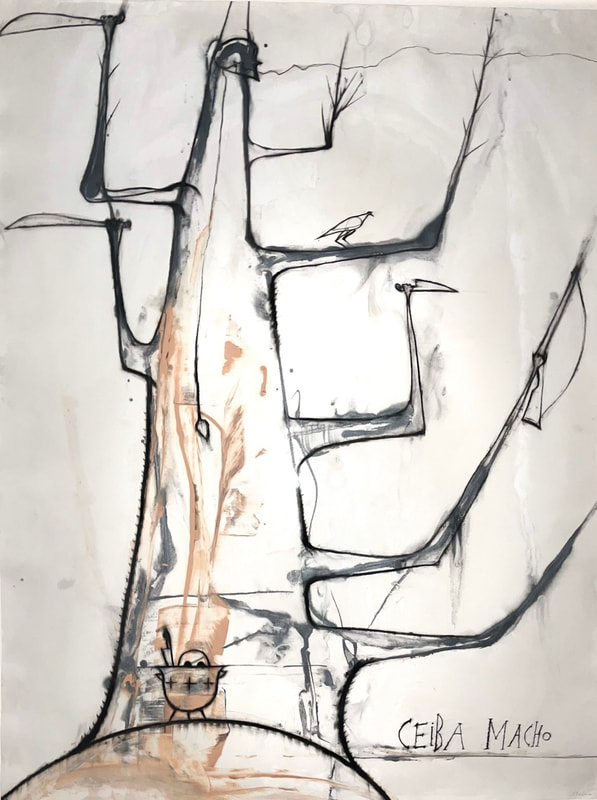

José Bedia

Collection of Dr. Carlyle Farrell / Interpretation by Dr. Carlyle Farrel

José Bedia (b. 1959) is a leading contemporary Cuban artist currently based in Miami. Described as a transcultural pilgrim (1) Bedia’s practice is rooted in his quest to better understand the spiritual beliefs of the peoples of Central Africa and the Indigenous Americas. An initiate of Palo Monte – a syncretic religion which combines the religious practices of the Kongo in Central Africa with the tenets of Roman Catholicism, Bedia’s work relies heavily on the iconic elements associated with this religion. In Cuban Spanish the word “Palo” refers to segments of wood while “Monte” refers to the forest. Ceiba, on the other hand, is a word derived from the Taino language and refers to a boat. The Ceiba was traditionally carved by these indigenous peoples to create dugout canoes which allowed them to traverse the waterways connecting the various islands of the Caribbean. The Ceiba is native to the Americas and West Africa and is regarded as sacred. The Mayans, for example, believed that four Ceibas held the universe together while the Tikunas of the Amazon believe that the Ceiba is the tree of life and that the Amazon River was created when a giant Ceiba fell to the ground.In Cuba, the Ceiba is believed to have magical powers and should never be cut down.

In the piece Ceiba Macho Bedia depicts a tree which is “armed” as if to protect itself from the evils of colonialism and oppression. In this work Bedia emphasizes the sacred nature of this tree by incorporating, at its base, an nganga. In the Palo Monte religion the nganga is a sacred vessel and is formally received by initiates who have completed the final level of their religious training. The three crosses on the nganga suggest that the vessel is blessed or baptized adding to its religious significance. Included in the nganga are a skull and knife – the latter, perhaps, a nod to Sarabanda the spirit guide associated with objects made of metal. Interestingly, in this work Bedia also incorporates a bird resting peacefully on the tree’s upper branches. Perhaps not to be interpreted literally, the bird may well represent the spirits of our ancestors who have gone before.

In the piece Ceiba Macho Bedia depicts a tree which is “armed” as if to protect itself from the evils of colonialism and oppression. In this work Bedia emphasizes the sacred nature of this tree by incorporating, at its base, an nganga. In the Palo Monte religion the nganga is a sacred vessel and is formally received by initiates who have completed the final level of their religious training. The three crosses on the nganga suggest that the vessel is blessed or baptized adding to its religious significance. Included in the nganga are a skull and knife – the latter, perhaps, a nod to Sarabanda the spirit guide associated with objects made of metal. Interestingly, in this work Bedia also incorporates a bird resting peacefully on the tree’s upper branches. Perhaps not to be interpreted literally, the bird may well represent the spirits of our ancestors who have gone before.

|

|

(1) Bettelheim J and Berlo J (2011). Transcultural Pilgrim: Three Decades of Work by José Bedia. Fowler Museum at UCLA.

Ceiba Macho, 1997

José Bedia (Havana, Cuba 1959 - ) was included in the Embassy Cultural House(ECH) exhibitions, Siting Resistance, in the summer/fall of 1990 held at the ECH, the Forest City Gallery(FCG), the Cross Cultural Learner Centre and the London Regional Art Gallery(Museum London). The ECH organized an artist residency for Bedia, his family and the Cuban artist Magdalena Campos Pons who travelled from Havana, Cuba to London, Ontario. Both artists were also invited to the Banff Centre for the Arts, Alberta in 1990 through the ECH’s initiative.

A solo exhibition of Bedia’s work was shown at the FCG and he was commissioned to paint a mural, The Sunnyside, on the facade wall of the Embassy Hotel. Campos Pons' solo exhibition was shown in the ECH and she was commissioned to do a room installation in the Embassy Hotel. Bedia's work was included in the exhibition Okanata, A Space/ WorkScene Gallery, Toronto in 1991 in solidarity with the Mohawks of Kanesatake (Oka Crisis). His work is in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario and private collections in Canada.

A solo exhibition of Bedia’s work was shown at the FCG and he was commissioned to paint a mural, The Sunnyside, on the facade wall of the Embassy Hotel. Campos Pons' solo exhibition was shown in the ECH and she was commissioned to do a room installation in the Embassy Hotel. Bedia's work was included in the exhibition Okanata, A Space/ WorkScene Gallery, Toronto in 1991 in solidarity with the Mohawks of Kanesatake (Oka Crisis). His work is in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario and private collections in Canada.

|

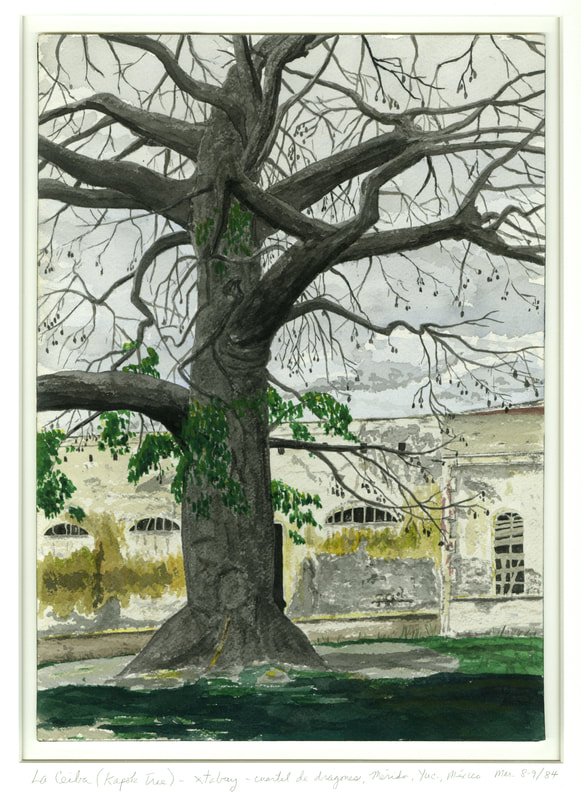

Ceiba (Silk Cotton Tree or Kapok), Merida, Yucatan, Mexico, 1984

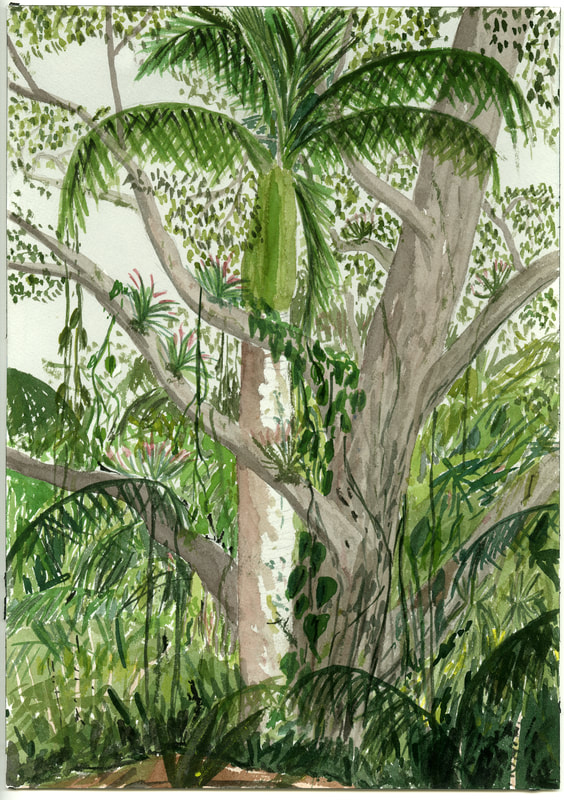

Caoba (Mahogany) and Royal Palm, Pinar del Rio, Cuba, 1988

|

Ron Benner“London, Ontario’s earliest artists were associated with its garrison and were officers trained in topographical rendering and watercolour painting. Young cadets in the British Army were required to develop an ability in drawing and painting landscape sketches because this training heightened an officer’s capacity to assess objectively the terrain before him. Some officers, such as Colonel Sir Richard Airey, Captain John Herbert Caddy, Deputy Inspector-General George Russell Dartnell and Captain Edmund Gilling Hallerwell, were quite proficient artists and spent leisurely hours outdoors sketching London and its environs. “ So wrote Tom Smart in the 1990 publication The Collection—London, Canada.

There is no mention of the cultural production of the Indigenous inhabitants of southwestern Ontario despite an occupancy of at least 10,000 years. The British military had occupied the London area in 1796 with the expedition of Lord Simcoe. By the end of the 1800's photography would replace the sketch or watercolour as the tool of prominence in the strategic analysis of the landscape. Watercolours as Evidence (Testimonials - to testify) Exhibit A: Colima Volcano, Colima, Mexico, 1977 In 1977, one year before Edward Said published Orientalism I made a journey with Jamelie Hassan and her son Tariq throughout Mexico. Jamelie, for as long as I can remember, always did watercolours which at the time I found to be extremely conservative and in fact I was quite openly disdainful...I considered my own production using photography to be very “avant-garde” (those in the arts who create or apply new or experimental ideas and techniques) without understanding the connection to the historical military meaning of the term. (Vanguard : the troops moving at the front of an army). At one point we were on the outskirts of Colima in south west-central Mexico and Jamelie was doing another watercolour. Noticing my ‘bad attitude’ she said to me : “If you think this is so easy why don’t you try doing one” and she tossed me a brush and watercolour paper. Rather than risk being considered a non-macho hombre I spent the next 30 minutes doing a watercolour - which I have brought with me to Saskatoon and offer it as evidence - Exhibit A of my own arrogance. It is in the collection of Jamelie Hassan. Excerpt from a presentation by Ron Benner from the Conference & Exhibition: The Humanities, Visual Culture and Testimony at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatatoon, October 2008, and subsequently published in a special issue of West Coast Line 64: Orientalism & Ephemera, guest edited by Jamelie Hassan, SFU, Vancouver, BC, 2010. Trees—December 2023 Although my work usually involves photography in conjunction with plants - both living plants (ie gardens) and dried materials, I have also completed over 200 landscapes in watercolour since I did my first watercolour in 1977. Most recently in August 2023, Jamelie and I completed a series of watercolours in Newfoundland. Trees have always been an important part of my work both photographically and in my watercolours. I have painted maple, oak, beech, pine and spruce in Canada. Banyans in Spain and Kenya. Jacarandas in Mexico. Here are three watercolours of trees that are native to Mexico which have an economic value but also have a mythological/cultural value: Cuban Royal Palm, Mahogany (Caoba), Silk Cotton (Ceiba) and Montezuma Cypress (Ahuehuete). |

Ahuehuete (Montezuma Cypress), Santa Maria del Tule, Oaxaca, Mexico, 1992

Marlene CreatesMy greatest aspirations are presently constituted by the six acres of old-growth boreal forest that I inhabit, and I’m slowly tuning my body and my reflexes to its details. I’m coming to know this habitat by engaging with it in various ways: corporally, emotionally, intellectually, instinctively, linguistically, and in astonishment.

These photographs are based on becoming familiar with a patch of old-growth boreal forest as a result of living with and among these trees for many years — a familiarity not just from looking but also through direct encounters using all my senses. I’m interested in the particularity of each tree—its “thisness”—and the circumstances that bring me to discern certain trees amongst the thousands in this forest. Even when I’m being my most attentive, there are still many trees I have not yet noticed enough to remember as individuals. Between 2007–2015, I photographed my hand using black-and-white film on 81 trees that came to my attention. But what I should say is my attention came to them. In 2018, I started re-photographing my hand using colour digital photographs on the same trees after an eleven-year interval, i.e. the ones from 2007 in 2018; the ones from 2008 in 2019 . . . and continuing until 2026, if all goes well. In the eleven years between photographs, changes can be seen in the trees themselves, the surrounding vegetation, and my aging hand. In three cases (so far), the trees on which I originally photographed my hand have been blown down in wind storms and hurricanes. In those instances, I photograph my hand in the empty spaces. |

Larch, Spruce, Fir, Birch, Hand, Blast Hole Pond Road,

Newfoundland 2007–ongoing |

Marlene Creates (pronounced "Kreets") is an environmental artist whose hybrid processes include memory mapping, photography, video, poetry, installation, scientific and vernacular knowledge, and site-specific multidisciplinary collaborative guided walks in the six acres (2.4 hectares) of old-growth boreal forest where she lives, at the edge of the 920-acre (372 hectares) Blast Hole Pond Conservation Area, which she helped establish in the town of Portugal Cove on the island of Newfoundland / Ktaqmkuk, Canada. For more information, please visit Marlene’s website.

|

Grandmother IV, 2001-2010

Grandmothers VI, 2001-2010

|

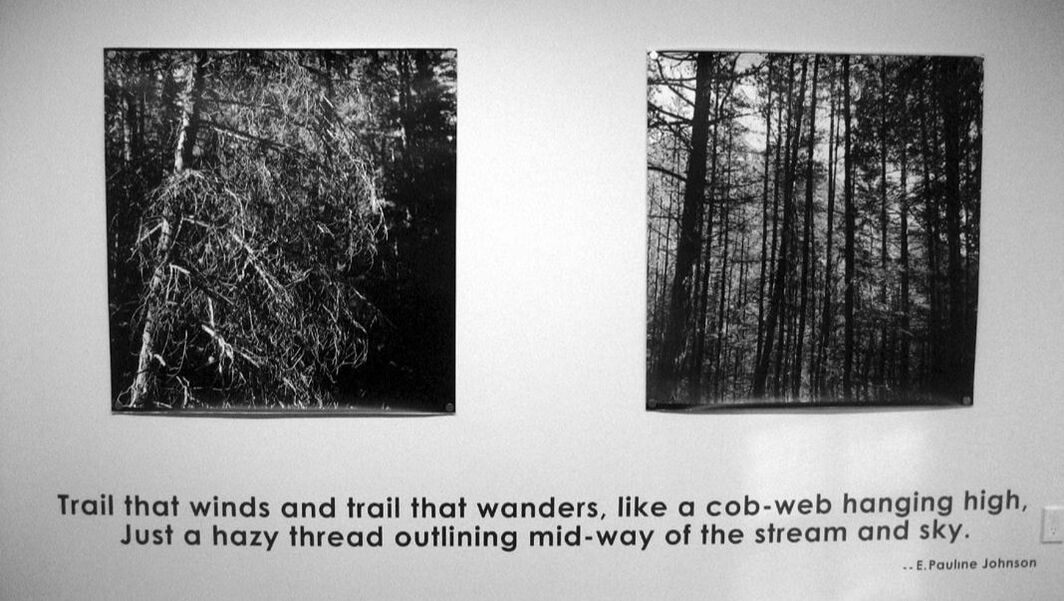

Patricia DeadmanOver the years, my work has remained consistent in its use of land as a metaphor for culture and the baggage we tend to carry with us in our daily lives. The Alpine Canadian Club’s A.O. Wheeler Hut in Glacier National Park, BC provided a specific place in history to interpret a century of shared colonial and mountain culture.

Constructs of self, tolerance, migration, privilege, and commodity are just a few of the threads that weave my personal narrative together, combined with the intangible sensory perception of sounds and smells. For this work, I drew inspiration from the contemporary writing of poet Jon Whyte as well as the contributions of early women trailblazers such as photographer Mary Schaffer and poet Pauline Johnson. Depending on who is telling the story, place provides a point of departure to recover, reclaim and maintain the personal balance that ultimately embodies the concept of resilience. Patricia Deadman is a lens-based visual artist, writer, and curator at the Woodland Cultural Centre. She obtained a fine arts diploma from Fanshawe College and a BFA in visual arts from the University of Windsor. She has participated in numerous artist residencies, including Banff, Alberta; Paris, France; Merida and Oaxaca, Mexico. She has exhibited since the 1980s, most recently in Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation 3, Contemporary Native North American Art from the Northeast and Southeast, Museum of Art and Design, New York, New York (2012–15), and Resilience National Billboard Exhibition, Mentoring Artists for Women's Art (MAWA), Winnipeg, Manitoba. Her works are in numerous public and private collections.

Grandmothers II & III, 2001-2010

|

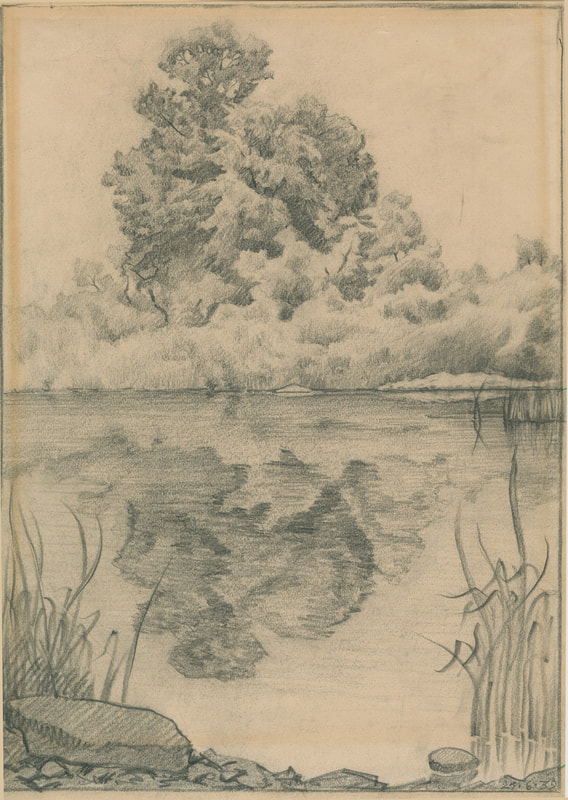

Selwyn DewdneyThe drawing, The Coves, June 25, 1939 by Selwyn Dewdney, was acquired by Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan with the assistance of Olivia Mossuto on December 18, 2023, from Gardner Galleries Auction, London, Ontario. The work was originally in the collection of Linda (Hoyle) Nicholas who had acquired the work from Irene Dewdney, Selwyn's wife. Linda Nicholas trained in Art Therapy with Irene Dewdney (1914-1999). With Dewdney and others, she founded The Ontario Art Therapy Association in 1979 and established the Post Graduate Diploma in Art Therapy at Western University in 1988. In a conversation with Irene the work was said to have been drawn at The Coves, the ox-bow lakes which were originally a part of the Antler (Thames) River. The tree in the drawing is possibly the Sycamore tree which still survives on the shore of one of the coves close to the Dewdney's former family home at 27 Erie Avenue. An Ontario Heritage Designation plaque recognizes the house and Selwyn and Irene Dewdney for their cultural contributions.

Selwyn Dewdney (1909-1979) was a Canadian writer, artist, illustrator, activist and pioneer in both Art Therapy and Anishinabek pictography. He was a close friend of Norval Morrisseau, Anishinabek artist. Dewdney was the editor of Morrisseau's book Legends Of My People. Selwyn and Irene Dewdney founded the practice of Art Therapy in Canada. In the fall of 1978, Jamelie Hassan invited Selwyn Dewdney to do a survey exhibition at the Forest City Gallery. The exhibition was coordinated by Ron Benner. Dewdney's novel Christopher Breton had just been published. He died on November 18, 1979 following heart surgery. In 1988, Paddy O'Brien curated a 3-person exhibition of the works of Clare Bice, Selwyn Dewdney and James Kemp at the London Regional Art Gallery (Museum London). His archives can be found at the D. B. Weldon Library, Western University and at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Ontario.

|

The Coves, June 25, 1939 by Selwyn Dewdney

Collection of Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan |

|

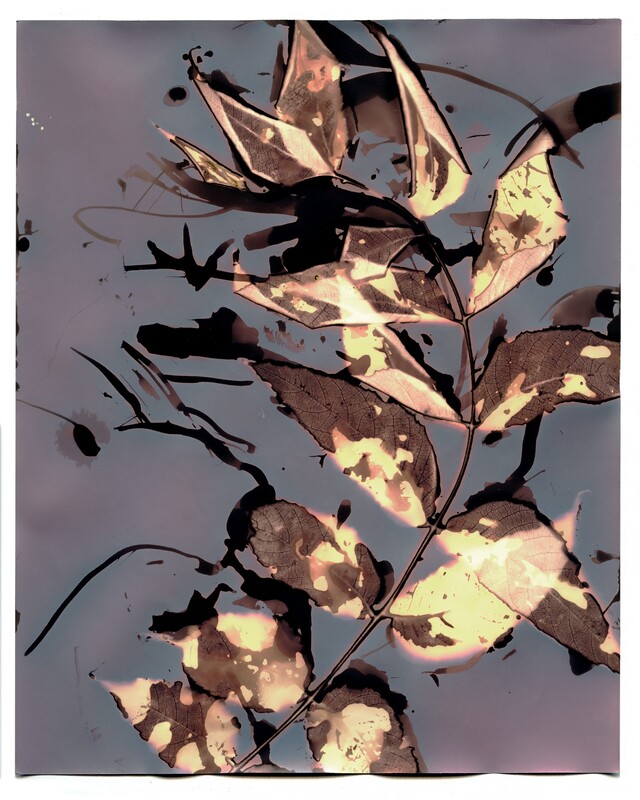

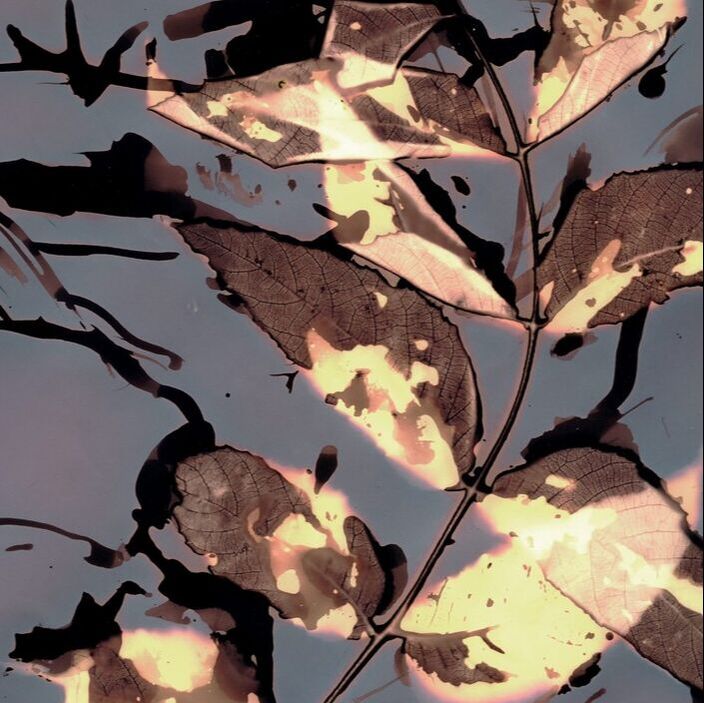

Phytogram of the Black Walnut Tree, 2023

|

Richelle ForseyIn 2021, I began collaborating with Dawn Matheson to develop How to Draw a Tree, a participatory site-specific art project bringing individuals living with mental illnesses together with trees for a year-long creative, caretaking, reciprocal engagement culminating in four immersive public sound walks on the grounds of The Arboretum, University of Guelph.

Storytelling, process-oriented, purposeful dedication to forest immersion, creativity, and experimentation, inclusive diverse collaborations, and intimate caretaking (a reciprocal one) are the driving forces behind this project. Each storyteller worked with an ad-hoc Tree Team to meet trees and build relationships, and ultimately find a tree(s) that their walks could build to or be built around. My role was to make the projects’ sound walks virtually accessible. I worked with each storyteller to bring their sound walk to life online, and created analog photo-based works of their chosen trees that celebrated the energy and characteristics of each tree species. The black walnut is a tall deciduous, shade providing, drought tolerant native species (North America) tree, with edible nutmeats and fern-like leaves composed of 15 to 25 oppositely arranged leaflets; each leaflet is serrated and may be up to 5 inches long. It is prized for its heartwood and medicinal properties, but also has a reputation for toxifying the earth within the range of its dripline with its own brand of herbicide called juglone that adversely affects many plants. However, it also supports the growth of many native species of flowers and shrubs such as Hostas, phlox, evening primrose, forsythia, St. Johnswart, Viburnum, and more. Experimenting with analog photographic processes is at the root of my practice and phytograms are made by soaking fresh leaves in washing soda and vitamin C and then laying the infused leaves on black and white photo paper and exposing them to sunlight. This process taps into the agency of the leaves (photosynthesis), activating the phenols (an ingredient in film chemistry developers) within the leaves that reveal a trace of their outlines and tissues on the emulsion of the paper. Once dry I captured the images digitally with a scanner, but the unfixed physical images will continue to develop and change over time, not unlike the trees themselves. |

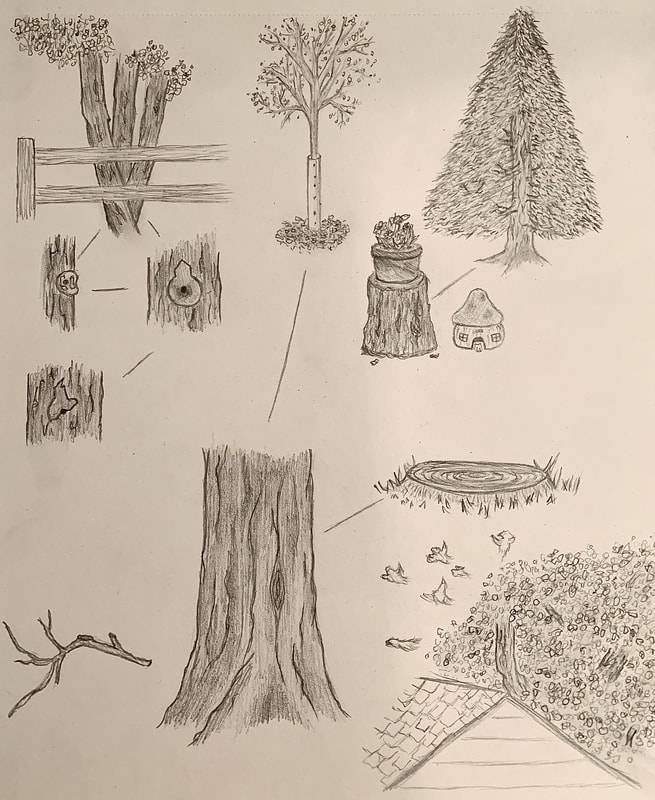

Alexis GreenDuring lockdown in 2020, I started using a small, leather sketchbook with thick pages to draw nothing but trees. I still don’t know why I choose to do this, but I know it helped me. When thinking about this new project, I knew I needed a bigger page, so I picked up a brand-new sketch book, similarly beautiful and fit for more trees, this time ones I knew personally.

I started drawing with a singular tree in mind, one which stands at Crawford Lake and is made up of three connected trunks, adopted by my grandparents many years ago. My grandma told me she picked that one as it represented her three children. I visited Crawford Lake for the first time in ten years to get a photo for this drawing and I was reminded of other trees there for the first time in so long that I decided I couldn’t only sketch the one. While there I noticed the old trail markers I used to run ahead looking for, desperate to be the first in my family to spot the next one. New trail markers have been put up, but the old ones were left, barely hanging onto the nails now. I saw hundreds of numbered tags, nailed in the same fashion to the tree trunks, indicating the tree had been adopted just as the one I had come to see. I decided these important enough to draw as well, and I continued to draw trees from my childhood which I haven’t seen in years. The pine tree in the backyard with an open space I could climb. It was cut down one day while I wasn’t home (something about it attracting too many bugs), but my dad saved the base of the trunk for me, and I kept it in my garden for years. In the front yard I remembered a massive tree which I could barely see the top of (I was probably just too small), which was also cut down after a summer where storms had broken branches off that nearly hit the house. The last inch or so of the trunk remained and I used to go outside and sit on it with my toys. After a while, the grass overtook it and I’m sure if you visited that house today, you would never know there had been a tree at all. Another tree was planted to replace that one on the opposite side of the yard. It was small, with thin branches and we used to hang tiny easter ornaments from it in the spring. Lastly, I sketched a tree from the grandparents’ backyard. It was massive, bigger than our old one, and was surrounded by a garden of my favourite flowers, Lily of the Valley. Small, black birds would nest there, and my grandfather would take a shovel or a rake out to the driveway where he would bang it on the concrete. The noise caused hundreds of birds to vacate the tree and fly over the house and far away, it was an event I loved to watch. |

Tree Sketches, 2020

|

|

Neither from the East nor from the West, 2014

|

Jamelie HassanPresented in the outdoor exhibition exploring Guildwood Park, Scarborough, Toronto curated by SUM°, May 17 – June 14, 2014.

Installation works are dependent on many factors but the site and its context are fundamental - what one might call the hospitality of the site to embrace the idea. A ruined entry way where the historical origins of these fragments is not known has an indescribable appeal to me. Salvaging sections of a destroyed tree from my home environment to work with and juxtapose in relation to the entry way of architectural fragments at The Guild is a modest act that is a counterpoint to the actions of the Clark's salvaging of fragments of architecturally historic buildings which were being demolished in Toronto's centre to this natural site in Scarborough. Language and the politics of language are often a part of my work including the use of Arabic calligraphy and text. In neither from the east nor from the west fragments of Arabic script in mirror- like fragments are inserted into hollow sections of a Norway Maple tree. The calligraphy fragments reflect the spaces above where the tree segments are placed in context to The Guild site’s entry way of fragments. The title and Arabic calligraphy fragments are inspired by the ceiling of the dome of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul which is of the verse Nur (Light) in the Qur’an. This installation, neither from the east nor from the west is dedicated in memory of my mother, Ayshi (Shousher) Hassan (1922-2014). |

Fern Helfand“Fire is not bad, fire is a life bringer, and the syilx people have lived in harmony with the land in a reciprocal relationship since time immemorial,” says sxʷuxʷiyaʔ, the Penticton Indian Band’s project manager for the Natural Resource Department."

“Fire is a tool our people have used for thousands and thousands of years to manage our timxw [life force], our lands, our animals, our berries,” says sxʷuxʷiyaʔ. https://indiginews.com/okanagan/bc-wildfires-a-wakeup-call-to- Fire is a natural and essential part of the life cycle of the dry pine forests that surround Kelowna, BC. The Syilx people, indigenous to the Okanagan, have always lived in oneness with these forests. The difference currently of course, is the large number of people who make their homes in the path of these now uncontrolled fires. Two and a half months after Kelowna’s devastating 2023 fire, I hiked up into the surrounding hills to find an unexpected, awe-inspiring grandeur in the trees and landscape of the burnt forest. Bare and curled branches created fine line drawings, alluring and graceful, etched against the sky. The earthen colours of the tall dying trees where the fire was less intense were overlaid on the newly revealed surface of the rocky terrain. They painted a haunting yet captivatingly beautiful canvas that conveyed the intricate balance between creation and destruction, and the omnipotent power of nature. |

November 2023 November 2023

|

Lisa Hirmer

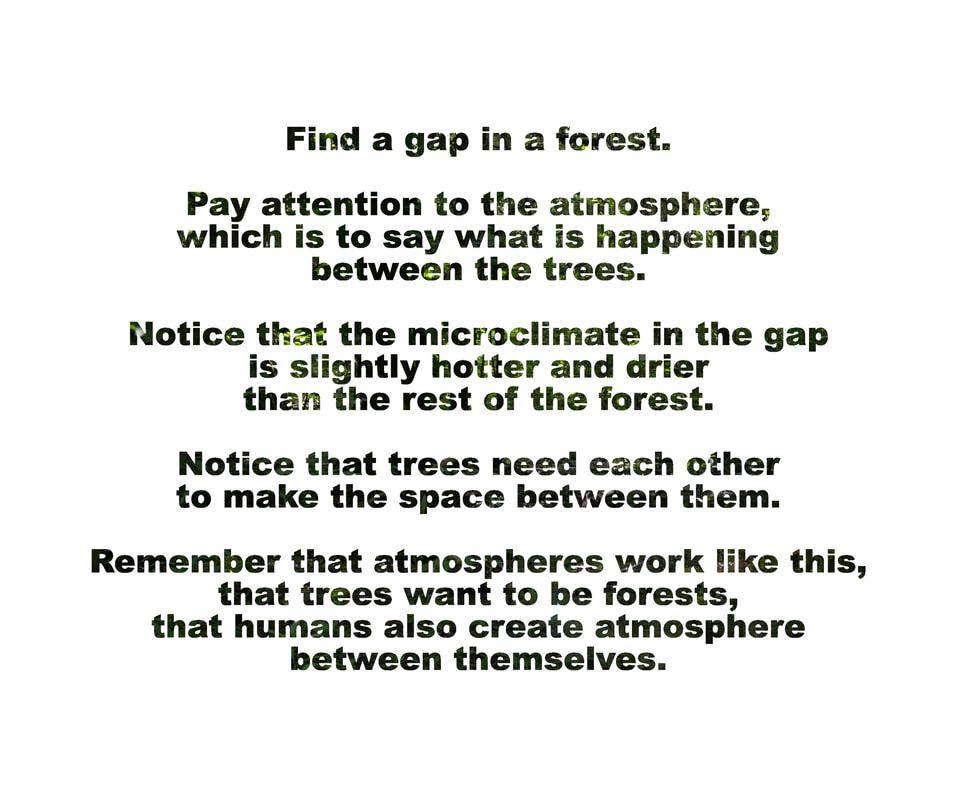

Atmosphere Score, 2020

Atmosphere Score is one of several scores about forests from Lisa Hirmer’s 2020 book Forests Not Yet Here (published by Publication Studio) about the relationship between human and arboreal bodies across different spans of time.

Penn Kemp

My poem celebrates the trees of London. An earlier version was commissioned by then mayor Joni Baechler for www.reforestlondon.ca and published in my collection, Barbaric Cultural Practice (Quattro Books).

Commemorating in Celebration Forest

|

Here’s to trees that celebrate soul!

We celebrate their verve. Here’s to tree as memory holder, tribute to our beloved’s ongoing presence. The Oak above Pond Mills hidden on a hillside of younger upstarts. The Beech behind Attawandaron where October puffball might pop. The Black Spruce and Tamarack that whisk us to clearer northern air as we walk through Sifton Bog like winds that wind along each limb. Trees we have known are trees we can meet by species. Once connected, always familiar, old friends to greet on any city street or in deep woods if we can slow down long enough to salute the Tree of Life in each. Light candelabra of Catalpa, Horse Chestnut, Pine, Balsam Fir, Juniper or Cedar cone. Sing a litany of names that belong here. Alder, Balm of Gilead, Willow galore. Glorious Maple, Butternut, sad slips of Elm, even intrusive Buckthorn now. |

Celebrate those graceful interlopers,

the Carolinians (Redbud, Tulip Tree, magnificent Magnolia) sheltering here at comfort’s edge in Snowbelt country. Here’s to lacey Walnut, Honey Locust, whose canopies carry us off to African plains: Acacia giraffes might browse or Le Douanier paint above his lion. Sycamore is our memory tree, shedding its bark like arbutus, its winter silhouette a ghostly skeleton, reminiscent of that other London’s Plane-shaded streets. Mother trees surround us, the very few left over from original forest we long paved over, old rotten stumps that settlers burnt to clear their land. Trees know their season, their reason for being. How each tree reaches out to become World Tree. We have so much to learn from not living on but with our place. We who live in this Forest City must ensure a name never replaces the reality of canopy. Long may our trees flourish for we can only prosper with our elder brothers, our mothers down the long lineage of those gone before. |

Penn Kemp has participated in Canadian cultural life for more than 50 years, writing, editing, and publishing poetry, fiction and plays. Her first book of poetry, Bearing Down, was published by Coach House, 1972. She has since published 30 books of poetry, prose and drama, 7 plays and 10 CDs of spoken word. She has edited a number of anthologies by Canadian writers since editing IS 14, the first anthology of Canadian women writers (Coach House Press, 1973). For more information, please visit Penn’s website.

Miriam Love

Family Tree

My parents planted trees for each of the kids: the big silver maple by the mailbox for Niles; Jenn’s ash, just outside her bedroom window and the center of the front shade garden; my dogwood at the back treeline by Farmer Schwartz’s field. Its growth and bloom were the clock and yardstick of my childhood. I posed in front of the tree for yearly Easter pictures documenting our growth. Some years we were full bloom and smiles; others, just about getting by.

“Brains are built over time, from the bottom up.”

The apple trees were Dad’s, planted two by two in the late seventies and early eighties. They grew into a mini orchard: eight trees, semi-dwarfs: Winesap, Golden Delicious, and McIntosh.

genes, experience, & synaptic pruning

Despite pruning every early spring, the trees grew tall and quickly. They, too, had on and off years, but every year they produced. The trees shaded the front yard and shielded the house from the road.

years

In my childhood, there were so many apples--apples to pick, apples to gather, apples to give away to friends, apples for crisps, barrels full of apples to take to the cider press, applesauce, applesauce, applesauce.

proteins & tangles

In the fall, Dad would peel apples in the evenings, his hands showing a slight tremor even then, and although they were tart cooking apples, those slices, offered off the tip of his paring knife, were so sweet and crunchy. We would store them in the garage and downstairs, and I loved their at-first-sweet and then tangy, rotting smell. Our freezer was packed with cider through the winter.

steal movement, memories.

By the time we had all left home, the trees were producing less, and even during the bumper years, more apples would fall to the ground. Dad would gather them into piles, and they would lay in the grass, forgotten, sticky with juice, buzzing with wasps, speckled with patches of sooty blotch and flyspeck.

Neighbours stopped in the laneway to ask if they could gather fallen apples for their crisps, for their pigs, for the deer.

& sleep.

The trees continued to grow taller, almost spindly. When the front McIntosh cracked, and a limb split off in a late summer thunderstorm, Mom and Dad could see that the tree was hollow inside. The professionals were called in, the situation assessed--that was the first apple tree to be felled.

One by one, they all came down, leaving the house. small and huddled, exposed to the road.

Family builds itself

Years after it was first planted, the roots of my brother’s silver maple caused problems for the mower—it had to go. Ash borers chewed through to its phloem of my sister’s ash. My dogwood is still in the back, standing amidst the graves of our dogs and cats: Katie, Cinders, Frank, Steve, Veronica, Bert and Ernie, Francie Lou. I phone my Dad to talk about the trees; his memories are still bright and clear.

from the bottom up.

My parents planted trees for each of the kids: the big silver maple by the mailbox for Niles; Jenn’s ash, just outside her bedroom window and the center of the front shade garden; my dogwood at the back treeline by Farmer Schwartz’s field. Its growth and bloom were the clock and yardstick of my childhood. I posed in front of the tree for yearly Easter pictures documenting our growth. Some years we were full bloom and smiles; others, just about getting by.

“Brains are built over time, from the bottom up.”

The apple trees were Dad’s, planted two by two in the late seventies and early eighties. They grew into a mini orchard: eight trees, semi-dwarfs: Winesap, Golden Delicious, and McIntosh.

genes, experience, & synaptic pruning

Despite pruning every early spring, the trees grew tall and quickly. They, too, had on and off years, but every year they produced. The trees shaded the front yard and shielded the house from the road.

years

In my childhood, there were so many apples--apples to pick, apples to gather, apples to give away to friends, apples for crisps, barrels full of apples to take to the cider press, applesauce, applesauce, applesauce.

proteins & tangles

In the fall, Dad would peel apples in the evenings, his hands showing a slight tremor even then, and although they were tart cooking apples, those slices, offered off the tip of his paring knife, were so sweet and crunchy. We would store them in the garage and downstairs, and I loved their at-first-sweet and then tangy, rotting smell. Our freezer was packed with cider through the winter.

steal movement, memories.

By the time we had all left home, the trees were producing less, and even during the bumper years, more apples would fall to the ground. Dad would gather them into piles, and they would lay in the grass, forgotten, sticky with juice, buzzing with wasps, speckled with patches of sooty blotch and flyspeck.

Neighbours stopped in the laneway to ask if they could gather fallen apples for their crisps, for their pigs, for the deer.

& sleep.

The trees continued to grow taller, almost spindly. When the front McIntosh cracked, and a limb split off in a late summer thunderstorm, Mom and Dad could see that the tree was hollow inside. The professionals were called in, the situation assessed--that was the first apple tree to be felled.

One by one, they all came down, leaving the house. small and huddled, exposed to the road.

Family builds itself

Years after it was first planted, the roots of my brother’s silver maple caused problems for the mower—it had to go. Ash borers chewed through to its phloem of my sister’s ash. My dogwood is still in the back, standing amidst the graves of our dogs and cats: Katie, Cinders, Frank, Steve, Veronica, Bert and Ernie, Francie Lou. I phone my Dad to talk about the trees; his memories are still bright and clear.

from the bottom up.

Miriam Love, a transplant from Ohio, lives and works in London, Ontario. Growing up, her mother taught her the names of all the plants, which she tried so hard not to remember and now cannot forget. She is co-founder of Antler River Rally, a grassroots environmental group that organizes monthly clean-ups of Deshkan Ziibi (Thames River).

Don McKay

Snotty Var

[He] went out in the garden where there was an abundance of balsam fir, and he brought back a strip of rind on which there were a number of myrrh bladders'. He cut open the bladders and squeezed the myrrh on the cut. Of course the bleeding stopped, and within a few days the cut had healed nicely.

—M. Hopkins, quoted in the Dictionary of Newfoundland English--

There is a balm in Gilead

and also in the boreal forest

where it sometimes goes by Balsam Fir

and sometimes Snotty Var.

Under its bark the myrrh

bulges into blister - a healing balm,

a glue, a gum to chew for exercise

and medicine.

The dance of Snotty Var goes

slow slow slow slow

slow, up to eighty years or so,

then quick. Its seedlings tarry in the shade,

dormant, acting as though being shrubs was all

they ever wanted, to fur the hillsides

so they resemble massive sleeping mammals.

Then some elders fall, thanks to

heart rot or a gale (or both),

the canopy gapes

and the little firs get growing,

thickening ring by ring and climbing

rung by rung, their needles guzzling light

[He] went out in the garden where there was an abundance of balsam fir, and he brought back a strip of rind on which there were a number of myrrh bladders'. He cut open the bladders and squeezed the myrrh on the cut. Of course the bleeding stopped, and within a few days the cut had healed nicely.

—M. Hopkins, quoted in the Dictionary of Newfoundland English--

There is a balm in Gilead

and also in the boreal forest

where it sometimes goes by Balsam Fir

and sometimes Snotty Var.

Under its bark the myrrh

bulges into blister - a healing balm,

a glue, a gum to chew for exercise

and medicine.

The dance of Snotty Var goes

slow slow slow slow

slow, up to eighty years or so,

then quick. Its seedlings tarry in the shade,

dormant, acting as though being shrubs was all

they ever wanted, to fur the hillsides

so they resemble massive sleeping mammals.

Then some elders fall, thanks to

heart rot or a gale (or both),

the canopy gapes

and the little firs get growing,

thickening ring by ring and climbing

rung by rung, their needles guzzling light

Don McKay is the multi-award-winning author of thirteen previous books of poetry, including Paradoxides; Strike/Slip, winner of the Griffin Poetry Prize; and Camber: Selected Poems, a finalist for the Griffin Poetry Prize and a Globe and Mail Notable Book of the Year. Angular Unconformity, a collection of poems, which was published by Goose Lane in 2014. McKay has taught poetry in universities across the country. He presently lives in St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Emmy MeredithI have always had a fondness for trees, and for forests in general. I can remember taking a trip with my family through the Canadian prairies and the desert-like areas in the Southwestern US and being struck by the barren landscapes. I quickly realized how much I took for granted the landscape of Southern Ontario, and its abundance of trees. These images are of trees in my front and backyard. The first is the large maple we have in front of our house. I enjoy watching its colours change with the seasons and watching the leaves fall and cover the ground in a blanket of red. The second photo I took is of a paperback maple tree in our backyard which has its bark peeling off. I find this tree fascinating, as the bark looks almost otherworldly when hit with sunlight.

|

Maple Tree, 2023

|

Paperbark Maple, 2023

|

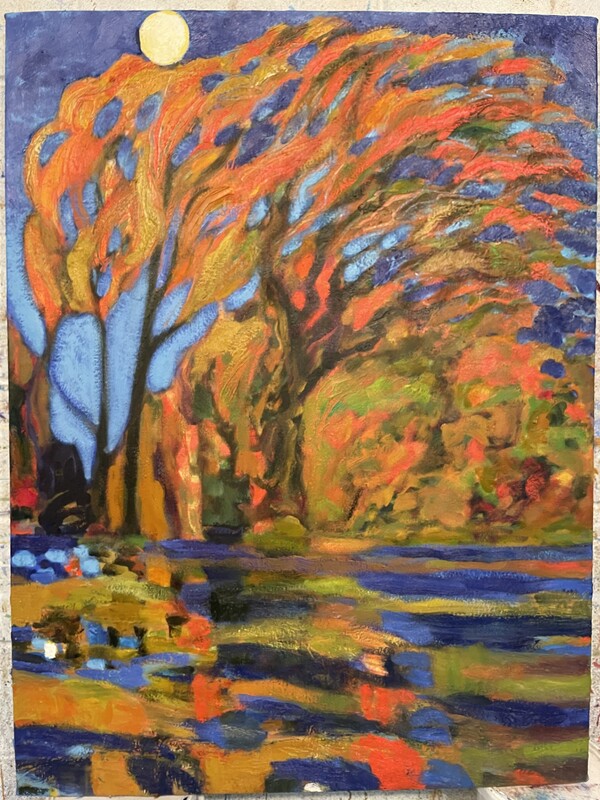

Moonrise in Autumn, 2023

Matsubara Tree, 2023

|

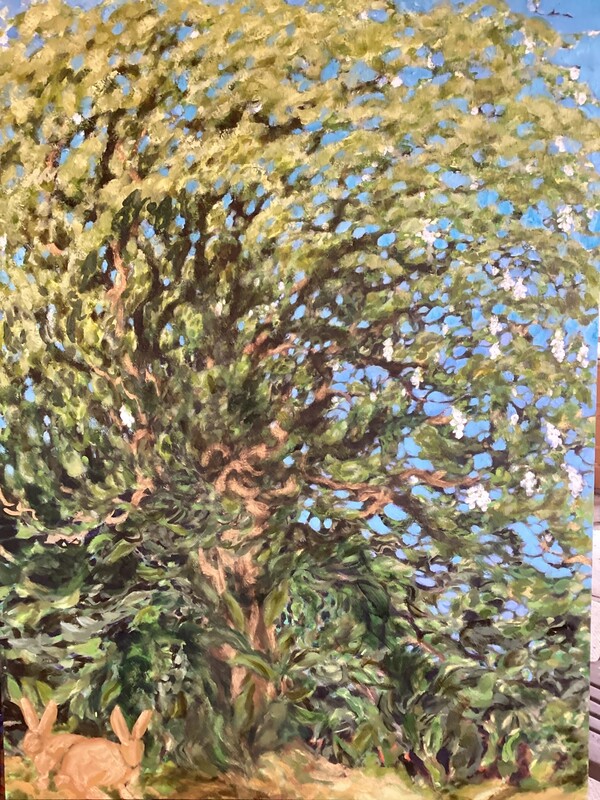

Catherine MorriseyThis [Sweet Locust in Bloom, with Bunnies] is a very old tree beside our pre-1880 house in the flood zone. It is one of a few remaining Sweet Locust Trees that stood in a row on Clarence Street when it ran down to the river. The houses are gone. The street is gone. There are a few old Sweet Locust trees that remain in a line.

Sweet Locust in Bloom, with Bunnies, 2023

|

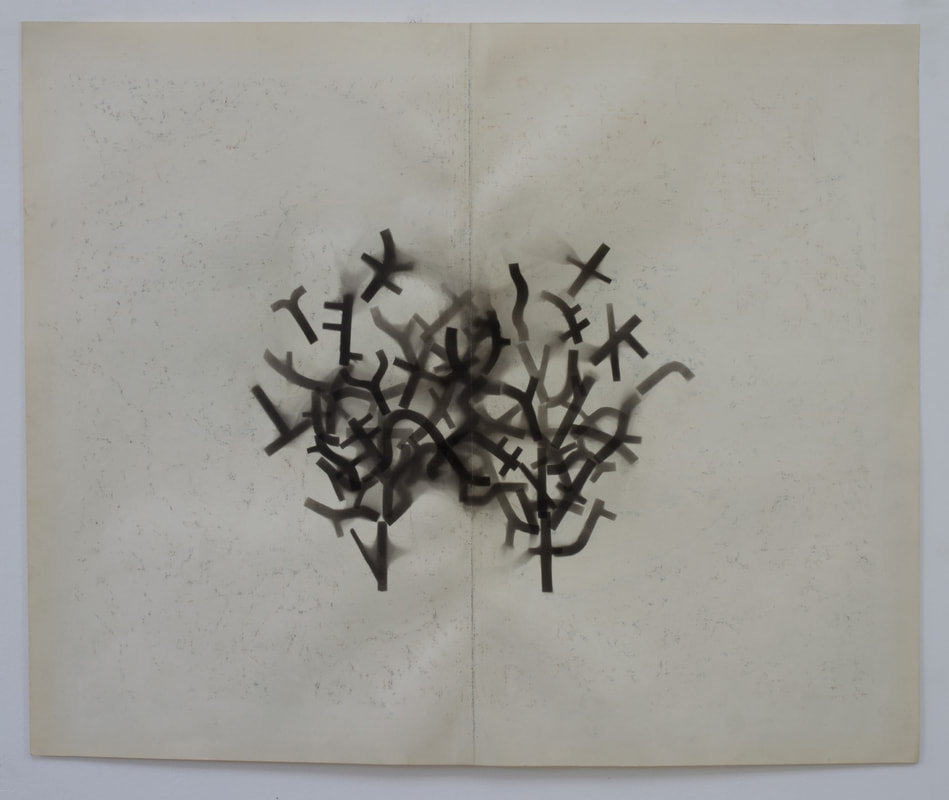

David MerrittThe work Means of Egress is the first piece to develop from an ongoing project involving the erasure of printed map plates sourced from the Mid-Century Edition of the Times Atlas of the World. The first volume of this edition was printed in my birth year, during an emergent period that the earth sciences today sometimes refer to as the Great Acceleration.

The map plate selected for the means of egress represented the Great Lakes region at the time. It is the only piece involving the addition of media on top of the inked remnants of the original maps. The entangled figures drawn on the erased surface were rendered using stencilled soot. |

Means of Egress, 2022

|

|

Curinga Plane Tree, 2023

|

Olivia MossutoThe history of a tree is not recorded to the same extent as the history of a human. For specific trees, few existing facts are known, notwithstanding extensive botanical data. For the 1000-year-old plane tree of Curinga, Italy, this is the case. What is known is that the tree was most likely planted by Basilian Monks who were cultivating different plants around the nearby hermitage of Sant’Elia. What is known with certainty is that the tree is alive and well, despite signs of aging and damage. A tree of this age has lived through the rise and fall of empires, the transit of civilizations and continuous climatic change. “The Gentle Giant” may have grown quietly, but in a certain kind of defiance to the past and present of hominin cultures that have existed in close proximity. Despite the continual, self-inflicted horrors of the human race, trees existed long before us, and will remain, long after we are gone. It should go without saying that trees do not stand still, and they do not look away.

|

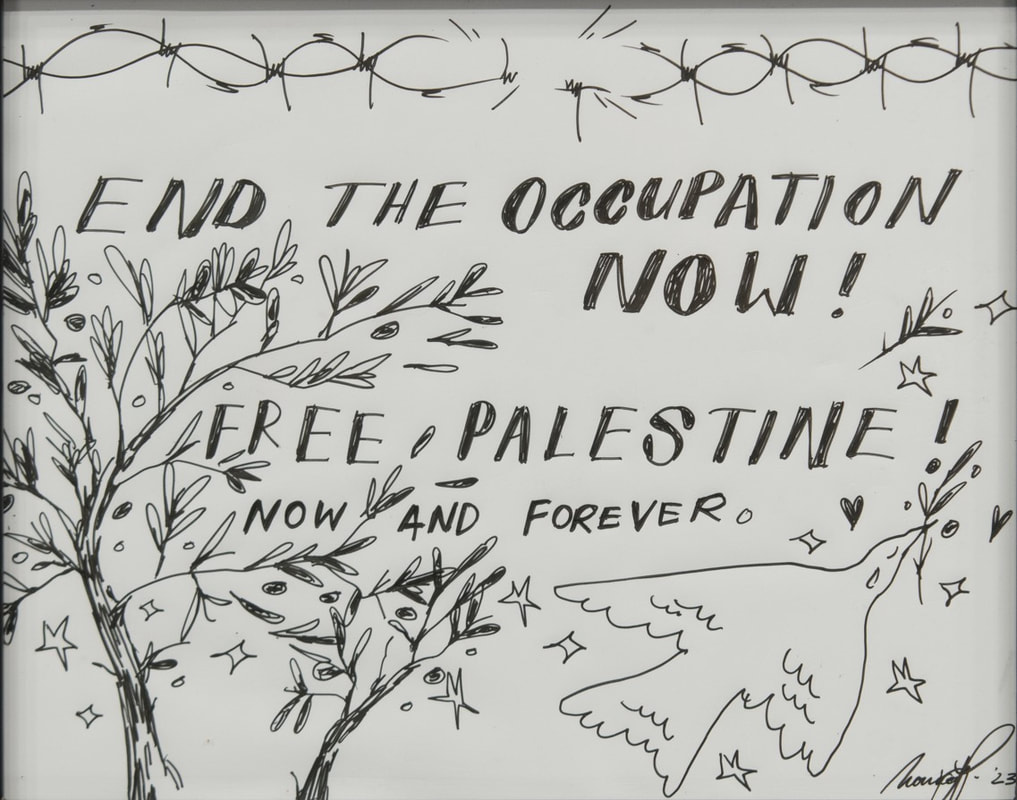

Monica JoyThis artwork includes imagery of a peace dove mid-flight with an olive branch, growing olive trees, broken barbed wire, among text which reads “END THE OCCUPATION NOW!”, “FREE PALESTINE NOW AND FOREVER”. Olive trees are native to Palestine, with great cultural and economical significance, and symbolically a representation of the national connection to the land. This work speaks to the ongoing genocidal violence occurring now in Palestine with the complicity of the Canadian government, which in turn is fueling the mass destruction of lives, land, and Palestinian heritage. Imagine a future within our lifetime in which Palestine is free, without existing under the occupation of Israel. This future is possible with the collective effort to take meaningful action against settler colonial violence globally. The artist fee for this artworks presence in this exhibition will be donated to the fundraiser Emergency Appeal for Palestinian Refugee Family which aims to assist a Gazan family seeking refuge in Canada. Contributions to this fundraiser will go directly to legal and travel costs. See more via: https://gofund.me/73c40417

|

Free Palestine Now and Forever, 2023

|

Monica Joy is an interdisciplinary queer artist and settler uses intricate line and thoughtful imagery to convey artwork which resonates with the significance of being alive. Their work ranges in media from ceramics and installation, to drawing and painting. Proceeding the Bealart Specialization program, Monica has been a resident artist of Good Sport Gallery & Studio since 2020.

|

Great Horned Owl, 2023

Cucumber Tree, 2024

|

Judith RodgerFor many years we have been observing great horned owls nesting from February to April in a hole in a venerable tree in Gibbon’s Park in London, Ontario. The symbiotic relationship between owls and trees is important for the ecosystem.

In 2023, the female owl moved to a new nest in a very old willow tree quite close to the tree that, after being used by the owls for about twenty years, developed a hole at the bottom of the cavity. I was amazed by how much better disguised the owl was in her new nest, rendering her more difficult for predators such as eagles, hawks and foxes to see. After the eggs hatch, the owlets begin to grow larger so that the mother owl gets higher and more visible in the nest. Eventually she leaves the nest during the day to the gradually maturing owlets, who perform for spectators. Meanwhile, throughout these months, the male discreetly stands guard in nearby spruce trees. This year two owlets hatched, grew in size and eventually flew away from the nest after entertaining hundreds of visitors and photographers from near and far. This photo is of a Cucumber tree (magnolia acuminata) that we planted as a three-foot stick in our front yard over twenty years ago. It is the only native magnolia tree and is quite rare in our area.

|

Roland Schubert

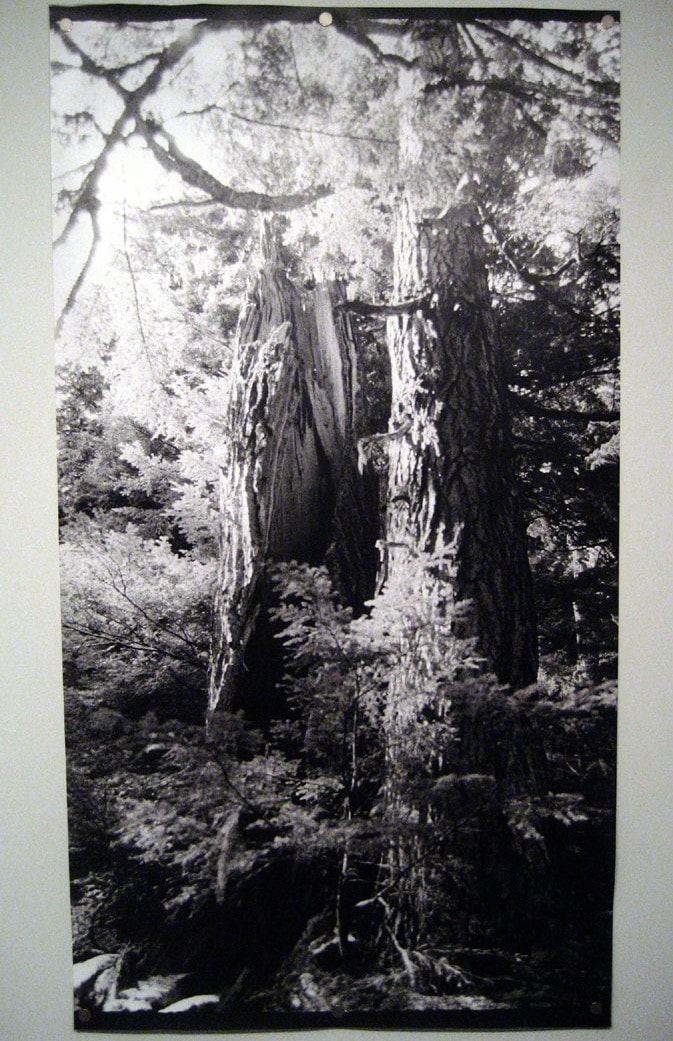

Bowen Island was clearcut in the late 19th to early 20th century but has since regrown and has, in part, been designated a provincial park.

The photograph was taken during a 2021 visit to the island to visit my son and his family.

If I suddenly disappear without a trace check Bowen Island, B.C.

The photograph was taken during a 2021 visit to the island to visit my son and his family.

If I suddenly disappear without a trace check Bowen Island, B.C.

Bowen Island, 2021

Ashley SnookA Body Within a Body Within a Body explores the concept of animality through an emphasis on ongoingness, kinship, and interconnectivity with and upon our earth - Terra. Within a dark space, the videos are projected on walls adjacent to each other, while subtle scents of pine, eucalyptus and cypress linger within the air to immerse the audience within the space. The scents helped visitors metaphorically consume nature by intaking the smell of natural oils—a sort of intake of animality. The poetic text paired with the videos collectively correlate to expressions of selfhood—that being of my own animality and connections to the more-than-human world. These scenes are personal moments of me exploring what grounds my animality: interactions with cows, seeing hair float in my bathwater, exploring forests and observing the trees, performances with soil, the various textures of my skin, observing chickens, my pet companion pups, and running in sand and snow. The trio of videos recenters the concept of animality at the forefront by exploring interconnectivity amongst species via the acknowledgement that everything, everyone is made of matter. By doing so, the videos collectively resposition the human experience closer to animality.

A Body Within a Body Within a Body, 2022

|

|

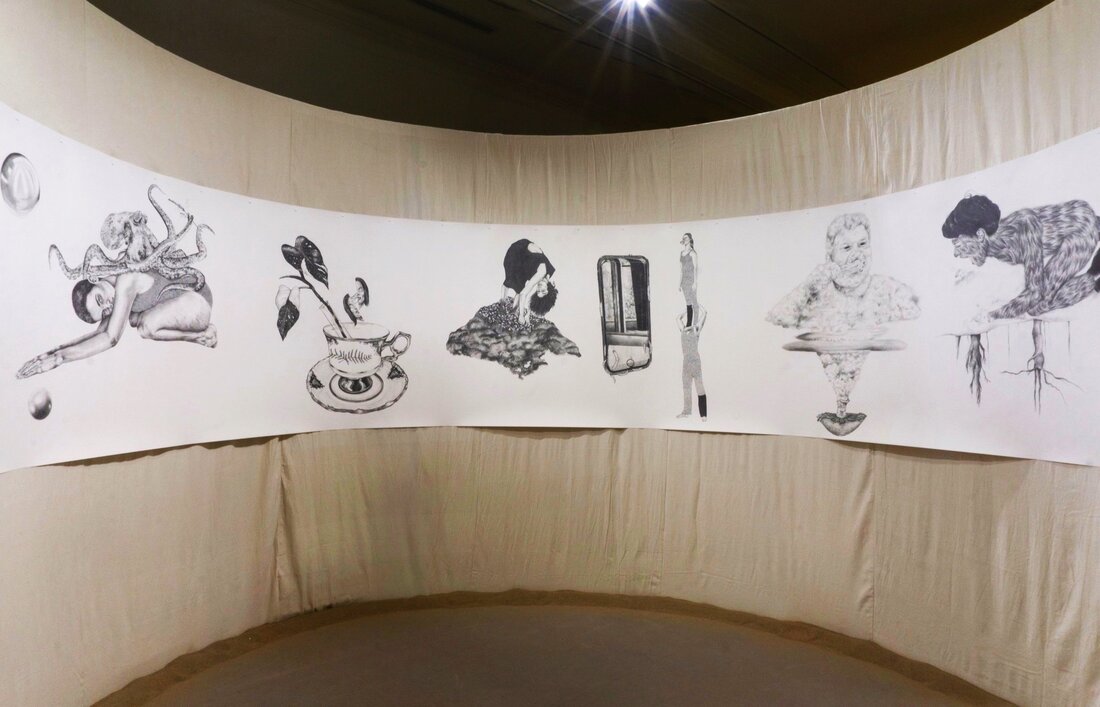

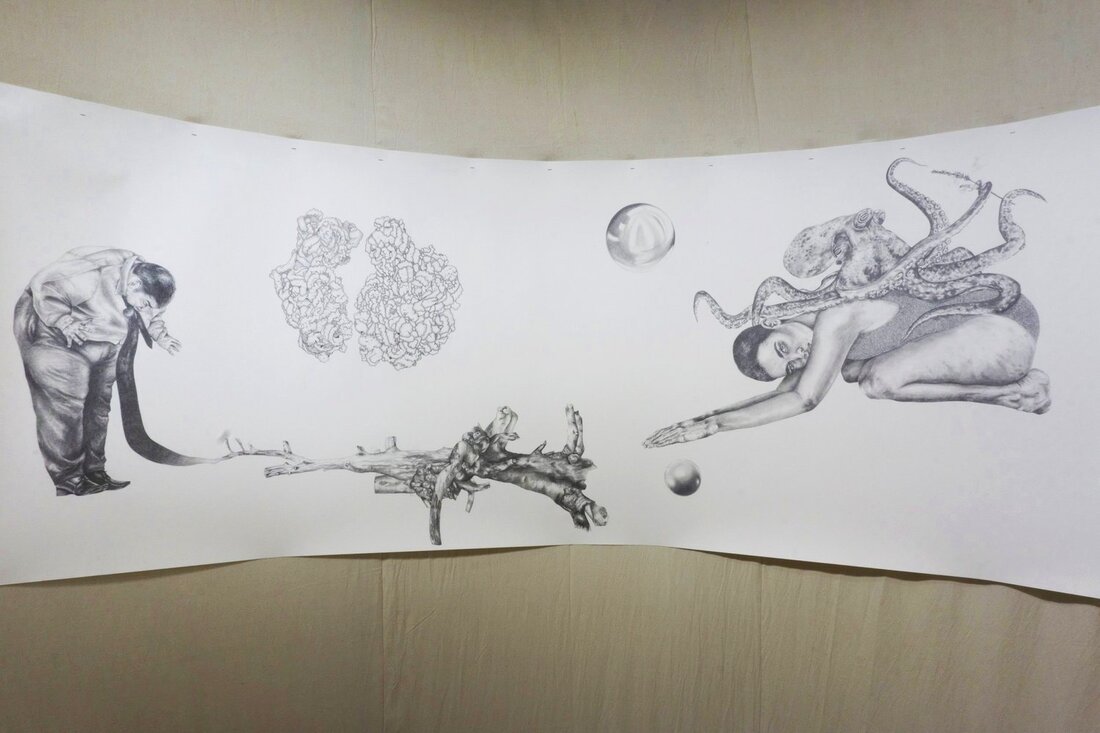

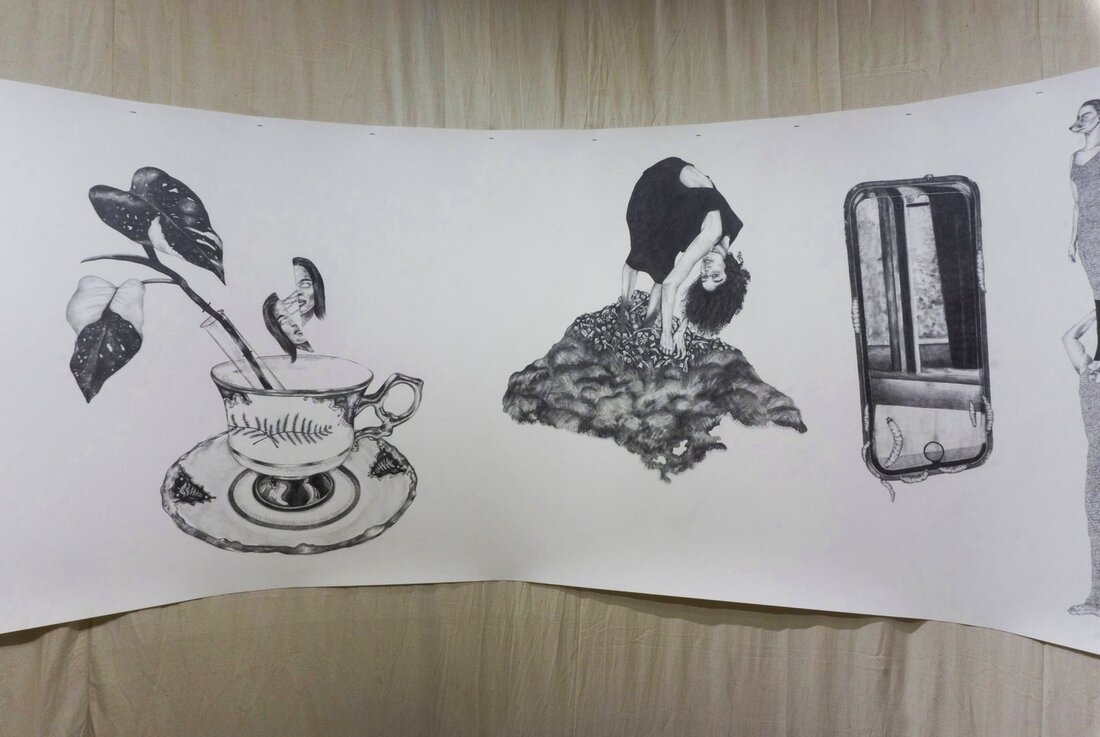

This large scale drawing addresses themes of the Chthulucene (a place in time where we are living and dying together in multispecies alliances), compost, reworlding, and concerns for the Anthropocene. The drawing seen in the photos is fastened on to a large rounded floating wall to immerse viewers within the work. As an homage to the video installation work A Body Within a Body Within a Body, over forty wax skull sculptures surrounds the gallery space—wax skulls of human, bear, and beaver all sitting on decaying rhubarb leaves harvested from my mother’s garden. The drawing demonstrates aspects of my methodology as while I create, I am in a constant practice of learning and unlearning through day-to-day observations, experiences, and worldly contributions. The drawing consists of imagery such as: a cloud person “overindulging” in a chicken wing, an office worker transitioning into a tree, wax worms consuming and digesting a plastic phone case, an indestructible micro-animal accompanied by composting insects, animals turning into compost, and other strange juxtapositions and figurative arrangements. The exterior of the drawing’s structure has a reflective mylar that distorts its surroundings, especially when viewers come close to the work. this allows for an abstracted visual experience, and perhaps, metaphorically, a distortion of self, suggesting a perspective-shift. Its purpose is to encourage viewers to imagine themselves differently, shape-shifting amongst the wax skulls and rhubarb leaves that surround the drawing space--which are themselves changing and decaying in the temporal process of decomposing and reworlding.

|

Chthulucene Dream-Land: States of Reality, 2022

|

Over Time, 2023

|

Heather (Von) SteinhagenMy time during digital mentorship with the Weather Collection allowed me to explore the connection between ancestry, personal practice, and our roles as land caretakers. The Weather Collection series, which emerged from a long-term research partnership between artist Lisa Hirmer and ULethbridge Art Gallery, aimed to create a sense of possibility in response to the climate crisis.

Throughout the mentorship in the spring and summer of 2023, I was able to stay curious and open to the guidance of the land. I engaged with my fellow artists in the mentorship, led by Lisa, who coordinated online talks with Smudge Studio and Jimmy Elwood. Through this process and personal meditations, I discovered my concept of quiet memories or blood/memories, which refers to memories passed down from one generation to the next, a term coined by Kiowa author N. Scott Momaday. During the mentorship, I revealed my private practice of bending trees. From this, Lisa introduced me to Trail Markers. For me, the sculpted trees marked trails I had used over decades and held special meanings. Though I had always kept this practice private, I felt compelled to investigate it further once I learned about trail markers. I remember when I discovered that my drawing doodles resembled petroglyphs, and it was a significant time when I saw the petroglyphs in Alberta. I also remembered my natural impulse to put herbs like cloves and sweet grass into the Kokum Dolls I sew, which I now know is medicine. These experiences made me contemplate the idea of blood memories and how our survival depends on our collaboration with the planet and all her elements. These private practices reflect a lineage to my ancestors, an unspoken bond to rituals and traditions. To reflect on my journey, I created this interactive digital story that captured the essence of how quiet memories surface when we wander. The ghost character in the story often represents myself in my work, and the background videos feature my most recent tree arch. The drawings reflect on nature and how nature and humans are interconnected and informed by each other. This mentorship allowed me to give in to my impulses to investigate and listen closely to the guidance of the land. I thought about how the birds know where to fly and how the bear cubs follow their mother carefully. This internal compass ignites when we are quiet, listen, and compassionate, and we know how to care for the land. It reminds us to rebuild our bond with nature and unite as a community to restore nature's natural abundance. I realized the importance of rewilding over the careful rewiring from nature that we meticulously created as a society. When we are quiet, we are always guided and wise over time. Overall, the mentorship has enriched my perspective on storytelling, blood/memories, and the significance of a sustainable future through collaborative action across species. Through slow, internal, creative investigation, I hope to continue exploring these themes and inspire others to connect with the land. |

Heather (Von) Steinhagen is based in Whitehorse, Yukon. Her passion for supporting creative innovation and soulful connections drives her career and art practice. She has roots from Cowessess First Nation (mother, Sparvier, Cree) and Germany (father, Steinhagen, 2nd generation German Canadian). Heather has a Visual Arts Diploma (Vancouver Island University, BC) and a Bachelor of Fine Arts, majoring in Community Arts Education (Concordia University, QC). She has worked as an Arts Administrator for the Yukon Arts Centre, Government of Yukon Tourism and Culture, and is the former Executive Director for the Yukon Arts Society. Heather is the Content Developer for the Canadian Crafts Federation and maintains a busy artistic practice. For more information, please visit Heather’s website.

Diana TamblynReconnecting With the “Forest City”

I grew up in London in the tree-lined streets of Old North, just a few blocks away from Gibbons Park. Some of my earliest and fondest childhood memories are of the weeping willows in the park - their branches just touching the water of the river, climbing the grand old tree by the swing set, swimming in the community pool, walking the dog, catching tadpoles, and just observing the change of seasons. Always exciting was seeing just how high the river would flood across the park in the Spring. So it’s not surprising that when I think of London, I think of trees. I moved away from London to go to school, and then to work. When I decided to move back home with my family 18 years later, we bought a house in Old North. I still love the grand trees of the area. As part of moving back home, I sought to reconnect with the city. I decided to do a “Tree Series” of ink drawings based on trees in my neighbourhood, and also favourite trees that Londoners nominated to the ReForest London. Londoners wrote in about trees that were important to them and why, and then the organization mapped these trees out on an online map. The exercise really forced me to see and appreciate my surroundings. It’s easy to walk without really seeing and observing, especially if the area is familiar to you. I found that one of the City’s favourite trees was just around the block from my house. To fully appreciate it - you have to stop, stand and look up, something that I had never done before. It’s a Hackberry tree and apparently one of the oldest trees in the city. When you stop and look up at it, it’s hard to deny its incredible beauty, and almost perfect shape. It’s a marvel that was in my own backyard that I had never really “seen” before. I drew it many times over, as well as other trees that were on the ReForest London map in my pen and ink style. This was back in 2010 and all of these years later, I think thanks to this drawing project, I try to remember to stop and look while on my walks and just take in the beauty of my surroundings, the magnolias in the spring, the leaves turning in the fall, newly fallen snow on a quiet morning. And I’m still drawing trees. 950 Colborne Hackberry, 2011

|

200 Collip Circle, 2011

300 Mt Pleasant, 2011

Bur Oak, 2011

|

Larry Towell

Fairy Creek Old-Growth Logging Protests & How Nature Saved Me From Covid

I’d been unable to travel for nearly two years due to covid, but in November 2021, I packed a suitcase for the Fairy Creek anti-logging protest camps in British Columbia. I’d be outside all of the time, so I felt safe. In the end, nature saved me during the pandemic by visiting some of those who were trying to save nature.

Since the spring of 2021, when blockades began, the RCMP had arrested more than 1,100 persons in the largest nonviolent, direct-action campaign in Canadian history. The dissent was being directed against old growth logging. Campaigners used their bodies with arms locked inside of “sleeping dragons” encased in cement and often buried, to close roads to logging trucks before police “extracted” them, which often took four hours or more. The blockaders included environmental activists and some First Nation members against logging company Teal-Jones. They also see current logging practises, including clear cutting, as non-sustainable and a contributing factor to global warming including the flooding that immediately followed my visit.

I’d been unable to travel for nearly two years due to covid, but in November 2021, I packed a suitcase for the Fairy Creek anti-logging protest camps in British Columbia. I’d be outside all of the time, so I felt safe. In the end, nature saved me during the pandemic by visiting some of those who were trying to save nature.

Since the spring of 2021, when blockades began, the RCMP had arrested more than 1,100 persons in the largest nonviolent, direct-action campaign in Canadian history. The dissent was being directed against old growth logging. Campaigners used their bodies with arms locked inside of “sleeping dragons” encased in cement and often buried, to close roads to logging trucks before police “extracted” them, which often took four hours or more. The blockaders included environmental activists and some First Nation members against logging company Teal-Jones. They also see current logging practises, including clear cutting, as non-sustainable and a contributing factor to global warming including the flooding that immediately followed my visit.

Red Dress Memorial for Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women on Clearcutting, 2021

Clearcutting, 2021

Further Reading and Viewing

|

|