A Garden of Resistance: Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan in Oaxaca, Mexico

with Marnie Fleming

Marnie Fleming, May, 2021

The Embassy Cultural House in London, Ontario, continues as a vibrant virtual space that provides artists with the tools to develop new methods of creative intervention. At the root of the cultural practice of the founders Jamelie Hassan and Ron Benner are the values of social change, community, and freedom of expression. They are activist artists, or provocateurs, who look at space as a social space, as a cultural space, and as a political space.

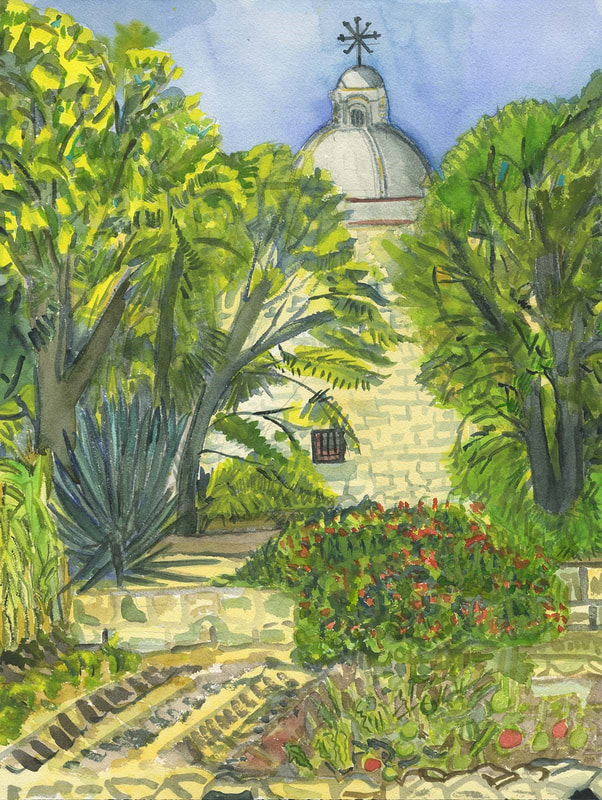

In looking over their 2013 exhibition of watercolours, The World is a Garden, shown at La Biblioteca Andrés Henestrosa in Oaxaca, Mexico, it is useful to position their watercolours in the context of not only the libraries and cultural exchanges, but also the very place of production: Oaxaca’s Jardin Etnobotánico.

Oaxacan artists, indeed, many Mexican artists, are also widely known for a long tradition of socially conscious art production. The vortex of such energy emanated from the fiery defender of all things Oaxacan, Francisco Toledo (1940-2019). Toledo vigorously defended Oaxaca’s cultural identity and much like Jamelie and Ron in London Ontario, he was a cultural force who championed indigenous peoples; aggressively campaigned for the 43 disappeared student teachers from Ayotzinapa; fought against genetically modified plants (especially corn) and was a singular impetus behind the city’s historical preservation. Indeed, many of the cultural institutions in Oaxaca are a direct result of Toledo’s activism, philanthropy, and ability to ignite the imagination, such as: the Instituto de arte Graphicas de Oaxaca,, and MACO Oaxaca Museum of Contemporary Art, Centro de Artes de San Augustin and of course, the Jardin Etnobotanico de Oaxaca.

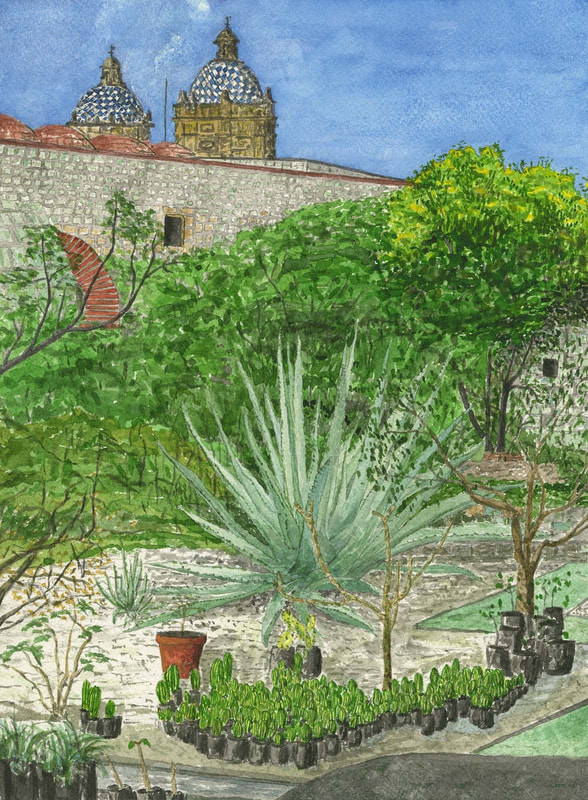

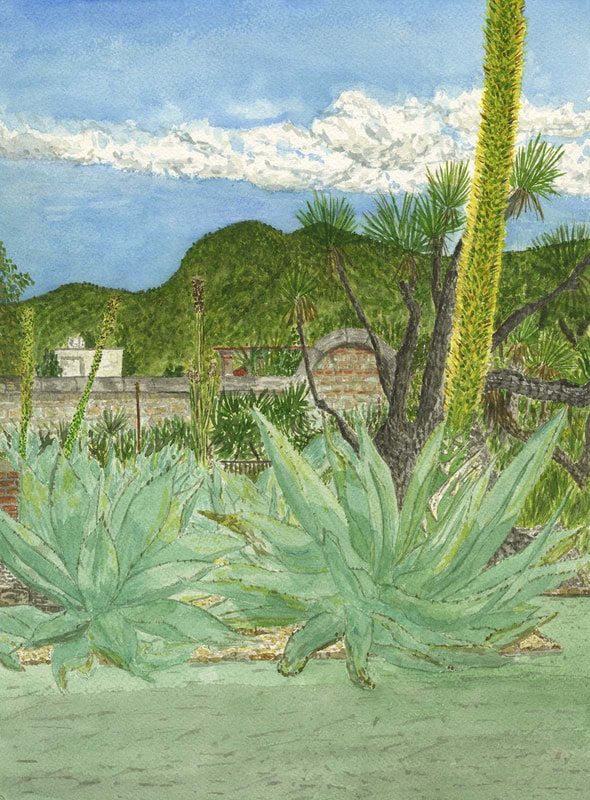

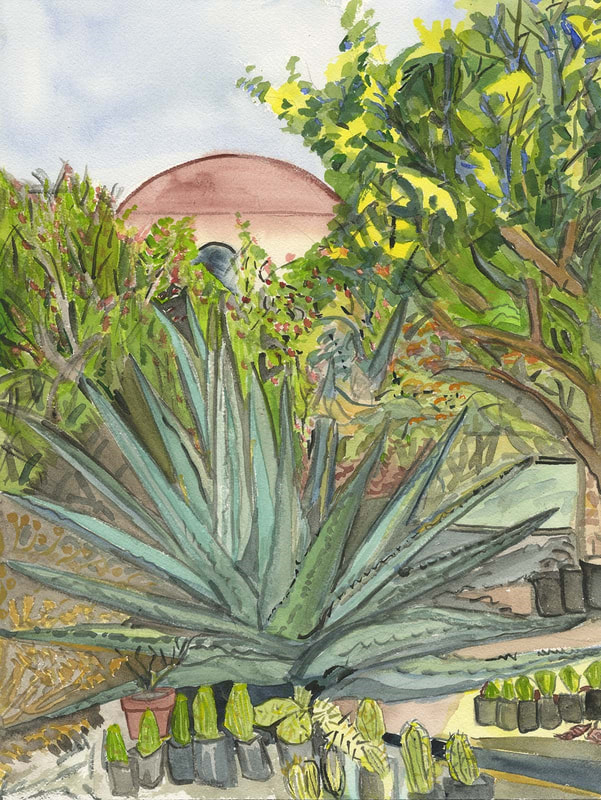

The watercolours in Jamelie’s and Ron’s The World is a Garden, are the result of a 3-month residency/fellowship at the Jardin Etnobotánico de Oaxaca. Working in this place over time, each of the artists was able to become familiar with the gardeners themselves and exchange ideas about the principals that ran parallel to their own interests, sensibilities and beliefs.

So too, in an era of global technology, the watercolour medium allowed the artists an opportunity for the “slow-study” of the garden’s structure and plantings. Being able to work for hours at a time in the garden, the London artists generated a very intimate reading of the site.

From their own site-related practices and installations, that include marvellous gardens and ponds, Jamelie and Ron continue to be passionate about the idea of a garden and what it takes to create a rich site for innovation and experimentation. They are entirely aware that a garden’s plantings and design are potent vehicles for contemporary investigation, for the expression of multi-layered histories, economies and the politics of food production.

Full disclosure: in 1987 – 1991, I lived at 514 Pall Mall Street in a studio/apartment, a former stable for horses, owned by Jamelie and Ron. (The bathroom and kitchen featured gorgeous Mexican tiles!) I first came to know of Oaxaca through these artists, almost 35 years ago. Today, I live 4 months of the year in this remarkable place with my husband, Colin Mooers. In 2013 we were coincidentally in Oaxaca when Ron and Jamelie were working in the Jardin Etnobotanico de Oaxaca (Ethnobotanical Garden of Oaxaca). It was a surprise for me to see them there along with another ECH member, Fern Helfand, now living in Kelowna BC. Living just a few blocks away from us was another ECH friend, and curator, Bob McKaskell. We all attended The World is a Garden exhibition at La Biblioteca Andrés Henestrosa.

What appears below is a text that I wrote in 2015 for our visitors which describes the history and developments of this exceptional garden. I hope it will provide yet another history and context for Jamelie’s and Ron’s watercolours.

Marnie Fleming, September, 2015

The state of Oaxaca, Mexico is in the narrow part of southern Mexico that bends east toward Central America. A staggering number of plants, fruits, vegetables, spices and herbs grow here and have made this place a ‘must’ for culinary explorers. Many come to this region to sample the cuisine but if you really want to understand Oaxaca’s history of rich indigenous cultures, its radical politics, its plants and food, one stop at the Ethnobotanical Garden provides it all. The plantings began in 1998 and today there are over 7,000 specimens and almost 1000 species, all native to the State of Oaxaca. As such, this world-class garden is alive not only with plant life but with remarkable human stories.

Housed in the former fields of the magnificent sixteenth-century Santo Domingo monastery, these six acres were transformed in the early 1860s into a military base. The Mexican military used the complex until 1993 when then Mexican President Carlos Salinas gave the military marching orders after being lobbied by intellectuals, activists and entrepreneurs, all interested in the prime central location. The state government promoted a range of options that included a convention centre, an upscale hotel, a McDonalds restaurant, and a parking facility.

The directors of the National Institute of Anthropology and History dreamt of a garden fashioned in the seventeenth-century European Baroque style. But it was renowned artist Francisco Toledo who threatened to stand naked under the proposed site of the Golden Arches and offer tamales in protest. He knew the pleasure that Oaxacans take in their own food, and thus, he enlisted artists to join him with placards that read, “Tamales, sí, Hamburguesas, no!” His protest was so popular that it wasn’t necessary for him to disrobe. But what he did lay bare was the need for indigenous protections and revealed the importance of the areas local food. In the end, he and the cultural community won the right to design and develop the location. El Maestro Toledo, as he is known, is not only an accomplished international artist but the founder and patron of a number of cultural institutions that have made Oaxaca the dynamic cultural centre it is today.

Toledo, working with Dr. Alejandro de Avila (trained in anthropology, botany and linguistics) and backed by the larger grassroots community, pooled creative talents and turned the space into a botanical garden, or more accurately, an ethnobotanical garden that would demonstrate diverse interactions between plants and peoples over the past several thousand years in the state of Oaxaca. Rather than simply presenting botanical specimens, this garden would display plants as integral to Oaxacan culture and history.

Dr. de Avila, the director of the garden, established an extensive database, selected plants, received donations from local communities and in some instances assisted in the rescue of mature specimens from the path of bulldozers during the Mexico-Oaxaca highway construction. After decades of neglect, the depleted soil needed to be built up again and watering issues resolved. An underground cistern and pipework now boasts the largest rainwater collection system in the State of Oaxaca.

The local Oaxacan artist Luis Zarate, who had never designed a garden before, was chosen to work with Toledo. He drew on the ancient step-fret motif to form a pattern in the soil. Composed of a turquoise mineral substance called tepate, the pattern is similar to architectural decoration found at nearby Monte Alban, the most important archeological site in the Oaxacan Valley, dating between 500 BC and AD 850. Additionally, Mr. Zarate employed narrow water rills to lead the eye from one section of the garden to the next. He incorporated views of the Santo Domingo monastery as a spectacular backdrop for the plantings, while the stone walls built during the military period set the garden apart from the exuberant pace of Oaxacan city life beyond.

Designed to incorporate the social history of Oaxaca, the Ethnobotanical Garden begins by introducing plants that over millennia have figured in Oaxaca’s cuisine and traditional medicine. Squash plants are planted with varieties of amaranth, chili peppers, beans and corn. Oaxaca was, in fact, the first site of corn domestication and today 65 varieties are grown in Mexico, while Oaxaca alone accounts for more than half, at 37 varieties. Other spicy collections of plants yielding buds, leaves, shoots, tendrils, stems and flowers make Oaxaca the food-lover’s paradise it is today.

More than two dozen species of bursera trees with their exfoliating bark and aromatic resin used for incense can be found here, along with the pochote tree, its trunk covered in sharp, stubby thorns. The superstars are to be found among the cactus, agave, cycad and palm. Together they create an imaginative ensemble of the hairy, waxy, prickly, and pony-tailed varieties: outlandish characters in a quirky but wonderful stage set.

In the agave zone there are more varieties of this plant in Mexico than anywhere else in the world and most of these are to be found in Oaxaca. Indeed, the fibers of the leaf (known as ixtle) are durable and versatile, used for the making of rope, sandals and scrub pads for cleaning pots. While some agaves are world-famous for alcoholic beverages such as tequila and mescal, even their thorns are used as needles for basketry. What’s more, parts of the leaf can be taken orally as a tincture to treat constipation and relief from excessive gas. Similarly, the Opuntia cactus, commonly known in Spanish-Mexican markets as nopales, have paddles that can be eaten raw or cooked in soups, salsas, stews and salads. So too, the fruit of the cactus is a refreshing snack eaten raw or used as a popular ingredient in candy, drinks, jams, and ice cream.

An insect that feeds off the juices of cacti is the cochineal, a tiny soft-bodied, flat, oval-shaped bug. It appears as white cottony flecks on cactus paddles and if you squish one, it oozes a crimson carminic acid. This colorant had many uses in pre-Hispanic Oaxaca, but it wasn’t until the eighteenth century that the tiny bug became Mexico’s second most valuable export after silver. It can be said that Oaxaca, post-Conquest, was founded on the cultivation of cochineal; its crimson coveted throughout Europe for oil paints, tapestries, dyes of clerical robes and cosmetics.

There is no shortage of levity and whimsy built into the design of the garden. For instance, its artistic founders placed a rather large, upright cactus along a path leading to the monastery’s arched window, as if to “give the finger” to the Spanish colonizers. Nearby, double rows of upright cacti look like fluted organ pipes reaching almost 6 meters high. Celebrated muralist Diego Rivera once used the Stenocereus thurberi as a fence, while many rural farmers in Oaxaca continue to use them for this purpose, too. Seen here in the garden, the organ pipe cacti are mirrored back to visitors in a pool that emphasizes their colossal size.

Creating a visual language that challenges not just the senses but embodies the very essence of Oaxacan history and culture is surely an extraordinary feat. The talented artist/designers, as well as the devoted gardeners who daily nourish the garden, have successfully demonstrated that this garden is linked to networks of historical and social relations. Indeed, it is their collective work that has encouraged a shift in how we view the natural world—not as something apart and unchanging but always in dynamic interaction with human stories.

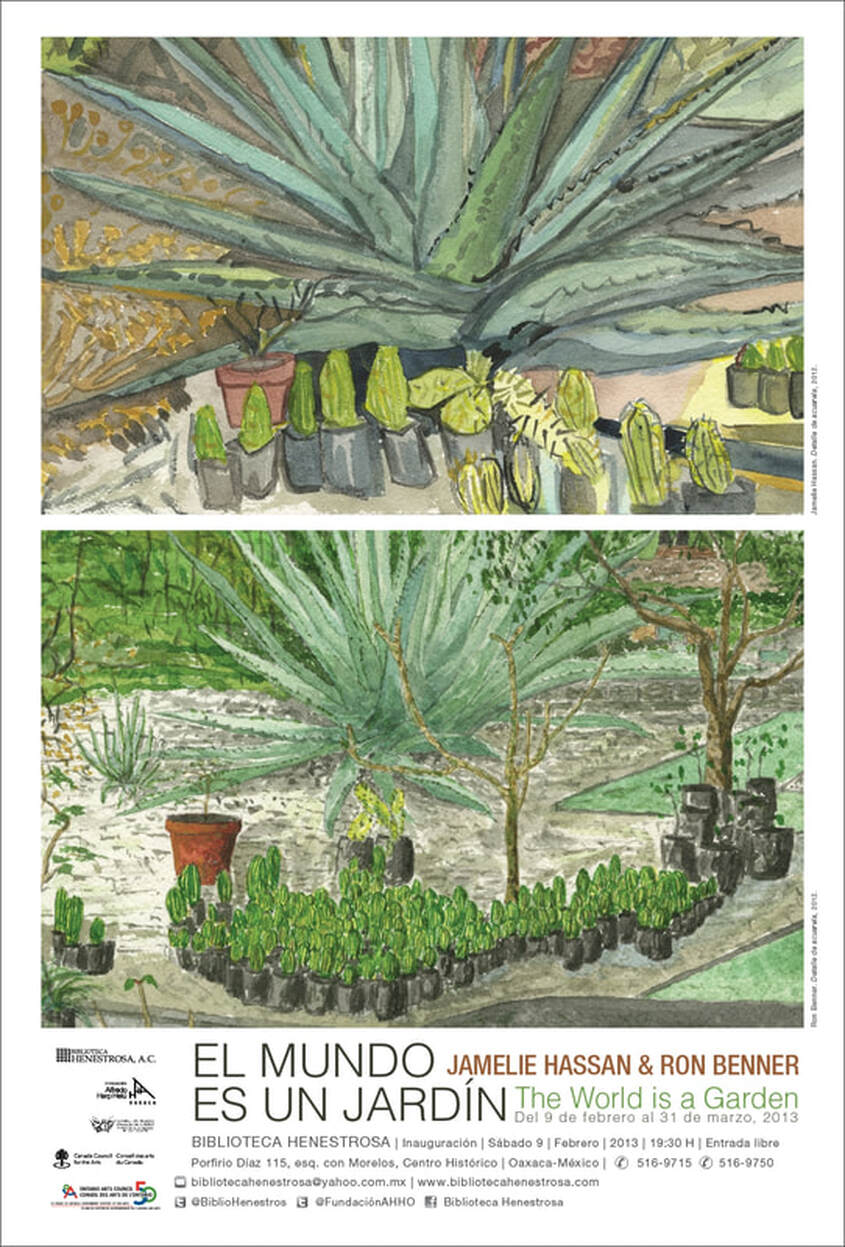

The World is a Garden: Jamelie Hassan & Ron Benner

La Biblioteca Andrés Henestrosa, Oaxaca

February 2013

This exhibition The World is a Garden: Jamelie Hassan & Ron Benner is the first exhibition to feature these two Canadian artists together. Jamelie Hassan and Ron Benner have lived, worked and organized exhibitions and projects together for over three decades. Both have created works that are often large scale mixed media and site-specific installations. Many of their works have addressed concerns which involve research in archives and libraries and address narratives that have been silenced.

Ron Benner has for many years addressed the conditions of industrial food production and the circulation of economic plants whose origins are from the Americas, in particular the movement of maize. His installation works involve photographic blow-ups combined with gardens that he creates in various public sites. These installations ask the viewer to critically examine the way colonialism continues to impact on diverse cultures and results in on-going injustices.

Jamelie Hassan has worked with various texts and languages which involve research in libraries and archives. Combining diverse materials and methods, her installations often involve keeping a notebook, watercolour painting or other works on paper, as well as photography, film works and ceramic. In some circumstances her work has directly overlapped and responded to some of the issues in Ron Benner’s work and vice a versa, reflecting the dialogical and creative context that is a large aspect of their relationship.

In this two person exhibition The World is a Garden: Jamelie Hassan & Ron Benner the artists are presenting both newly created works and some earlier works that reflect their concerns and respond to the site of the library, as well as the city of Oaxaca and the cultures of Mexico. Both artists have travelled and worked in Mexico since the mid - 1970s and the cultures of Mexico have always been an important inspiration. In 1976 and 1977 Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan made their first visits to the state of Oaxaca. Later, in 1992 the artists spent three months doing research in Oaxaca. It was at this time that Jamelie Hassan and Ron Benner first met Freddy Aguilar, formerly the librarian at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Oaxaca. In 2011, three students from Oaxaca visited London, Ontario and met Ron Benner at the site of the artist’s Museum London garden installation. The visitors agreed to deliver a copy of Benner’s publication, Ron Benner: Gardens of a Colonial Present to Freddy Aguilar for the library in Oaxaca.

Around the same time, Jamelie Hassan began an email correspondence with Ana Paula Fuentes, former Director of Museum of Textiles of Oaxaca. During a return visit to Oaxaca in 2012, after a 20 year absence, the artists did a series of watercolour paintings on site in the Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca. These watercolours as well as photographic and mixed media works by Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan will be presented. Among the works included, are their early notebooks and drawings from their first travels to Mexico. The title of the exhibition is from a text by Ibn Khaldun, (1332-1406) Arab traveller, scholar, diplomat and author of “Al Muqaddimah”, a seminal history of philosophy. The title pays tribute to Ibn Khaldun’s life and work. The line reads “The world is a garden whose walls are the state”.

Ron Benner: Based in his hometown of London, Ontario, Ron Benner is a visual artist, activist, gardener, curator and adjunct professor in the Visual Arts Department, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario. Co-founder with Hassan of the Embassy Cultural House (1983 - 1990) he was the former artist director of the Forest City Gallery, an artist-run centre in London, Ontario established in 1973. His photographic garden installations have been installed across Canada and in Seville, Spain (1992) and Salamanca, Spain (2003). The recipient of numerous awards Benner’s works are in public collections, including the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, the McIntosh Gallery, The University of Western Ontario, Museum London, London, Ontario and the Casa de Las Americas, Havana, Cuba. His most recent installation is presently on exhibit in Bread and Butter at the Jackman Humanities Institute, The University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada until June 2013.

Jamelie Hassan: Based in her hometown of London, Ontario, Jamelie Hassan is a visual artist and is also active as a lecturer, writer and independent curator. Hassan has coordinated numerous international programs and is active in artist-run centres in Canada and was a founding member of the Forest City Gallery, London (1973) and Embassy Cultural House (1983-1990). Her works are in numerous public collections, including the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, the Art Gallery of Ontario,Toronto, the McIntosh Gallery, The University of Western Ontario, Museum London, London, Ontario and the Morris & Helen Belkin Art Gallery, the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia. In 2001, she was awarded the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts, the Chalmers Art Fellowship (2006) and recently completed a four month artist in residence at La Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, France (2012). A survey exhibition, Jamelie Hassan: At the Far Edge of Words which has been touring Canada is presently on exhibit at Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa, Canada until March 2013.

Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan extend their thanks to Freddy Aguilar, Director, La Biblioteca Andrés Henestrosa, Oaxaca; Alejandro de Ávila, Director, Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca, Mexico; Ana Paula Fuentes, former director of Museo Textil de Oaxaca; and to Diego Sanchez and the other dedicated guides and workers at the Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca and in London, Ontario, thanks to Colour by Schubert, Marie-France Arismendi, Mireya Folch-Serra and Anthea Black for their assistance.

Ron Benner gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Ontario Arts Council in the presentation of his work in this exhibition.

Jamelie Hassan gratefully acknowledges the Canada Council for the Arts and the La Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, France for their support of her work presented in this exhibition.

Acknowledgments by Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan, May 2021

The Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca is located within a UNESCO world heritage site which includes the garden with a large selection of plants from the state of Oaxaca, a propagation centre, as well as a library of books on plants and gardens. The propagation garden is a significant resource, supplying seedlings for gardens and parks throughout the state of Oaxaca.

Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan extend their thanks to Alejandro de Ávila, Director, Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca, Mexico; Freddy Aguilar, Director, La Biblioteca Andrés Henestrosa, Oaxaca; Ana Paula Fuentes, artist and former director of Museo Textil de Oaxaca; and to Diego Sanchez and the other dedicated guides and workers at the Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca. The artists also acknowledge their thanks to the following individuals for their dedicated work on this feature on the Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca: Tariq Gordon, Kuwait/Canada for his website design and technical skills, and in Canada, Roland Schubert for photographic support and Marnie Fleming for her inspired writing on this series of watercolours and sharing her reflections and connections to the culture of Oaxaca, Mexico. ◊

Banner image: detail of watercolour by Ron Benner