Art as engagement: creative ideation in the fight to save the planet

In conversation with Christina Battle, Ron Benner, and Shelley Niro on how art is changing our relationship to the environment, and mobilizing communities to care, grow, and solve together.

As of this summer, Ron Benner’s garden installation As the Crow Flies, on the grounds of Museum London will officially turn 16 years old. The work is part of a series that combines gardening, installation and mounted photographic panels, while exploring the history and economy of food cultures. It is a flourishing visualization of his research depicting sites due south of London, Ontario along the meridian of longitude 81.14. In spite of a global pandemic and impending climate catastrophe, Ron’s dedicated audience patiently awaits for the garden to be installed, planted, and thoroughly watered.

“They were waiting to see if I was going to show up – and there I was. I have all the plants ready and I’m working away and these people were so happy that I was there,” Benner remarks.“For these times especially, it’s been quite humbling seeing just how people needed me. I knew that people liked my gardens, but I didn’t realize how really important it was to them until now,” and how important it is - not just for a human audience, but for the toads and birds that return to their comfortable home year after year.

“They were waiting to see if I was going to show up – and there I was. I have all the plants ready and I’m working away and these people were so happy that I was there,” Benner remarks.“For these times especially, it’s been quite humbling seeing just how people needed me. I knew that people liked my gardens, but I didn’t realize how really important it was to them until now,” and how important it is - not just for a human audience, but for the toads and birds that return to their comfortable home year after year.

Art may seem to lack in potential, if one considers the breadth of capable disciplines poised to engage with the environment and problematize degradation. However, contemporary meanderings have proven that the arts cannot be reduced to mere aestheticism. Today and right now, the boundaries of art continue to broaden, creating new opportunities within creation and methodology. As a result of this shift, environmentally-engaged works have diversified conversations in a way that does not neatly conform to medium or movement.

Art might not be the method that communities will employ to solve complex environmental issue, but it can offer genuine considerations on how we transform our approach. In order to address issues like climate change, loss of biodiversity, and food sovereignty - an interdisciplinary perspective is the only way forward. For the casual consumer, art exists in object-forms like painting and sculpture, but beyond such parameters are socially-engaged, evanescent works that have yet to make their way into public purview – past the art-world boundaries into the real world. For years, many Canadian artists have been addressing environmental challenges through their own practices.

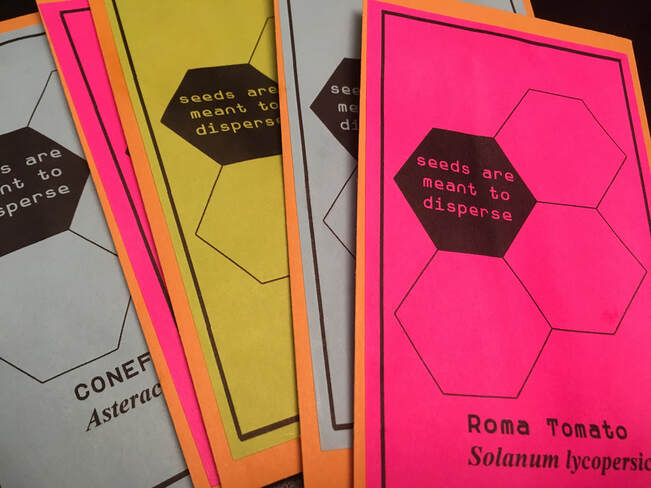

Multi-faceted media artist and curator Christina Battle continues to garden and share seeds as a non-committal and increasingly passionate way to engage with the world. In 2015, her practice of sharing seeds and exploring economies of exchange became a formal artwork—moving outside of her daily life and into the scope of intentional criticality. Battle’s practice can only be described as multi-disciplinary, centering heavily on topics of disaster and environmentalism.

“For me, growing plants and having the opportunity to watch plants grow, changes the way that I think about time and space and my own sense of busyness and my own speed in the world,” Battle says. “I think that all of that is important in shifting a framework in thinking about a worldview.”

For Shelley Niro, award-winning artist and filmmaker, her memories of the outdoors have been a driving factor since she was a child; “a lot of the work that I do comes back to remembering what it was like to be outside and feeling the air and having bugs bite you– it’s like you’re participating with the world.” It is in this way that Niro adeptly underscores the power inherent in nature, a force that inspires us to work for and with the earth.

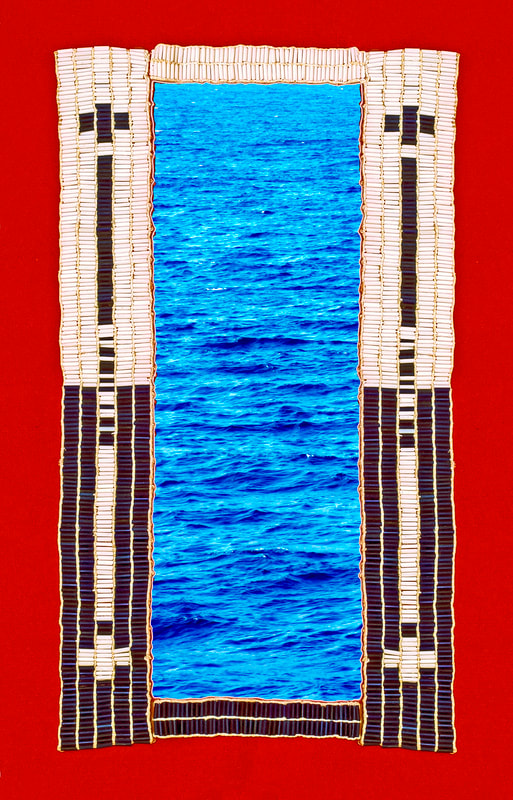

In her work, Pieta #1, a deep respect for the earth has been visualized with care, in the blue of the water and the complexity of the wampum frame set against a bright red background. In Niro’s own words, “I wanted to use that image of water as an expression of being born – since you come into the world through a body of water." The connection is obvious when it has been vocalized, spelled out, depicted - yet humans tend to forget, and continually set out to mine our collective, live-giving resources.

Whether it is through the greatly enlivened installations of Ron Benner, the intricately vital photographs of Shelley Niro, or the billboards on disaster by Christina Battle – art is being activated in many forms, in a multitude of spaces, right here in Ontario.

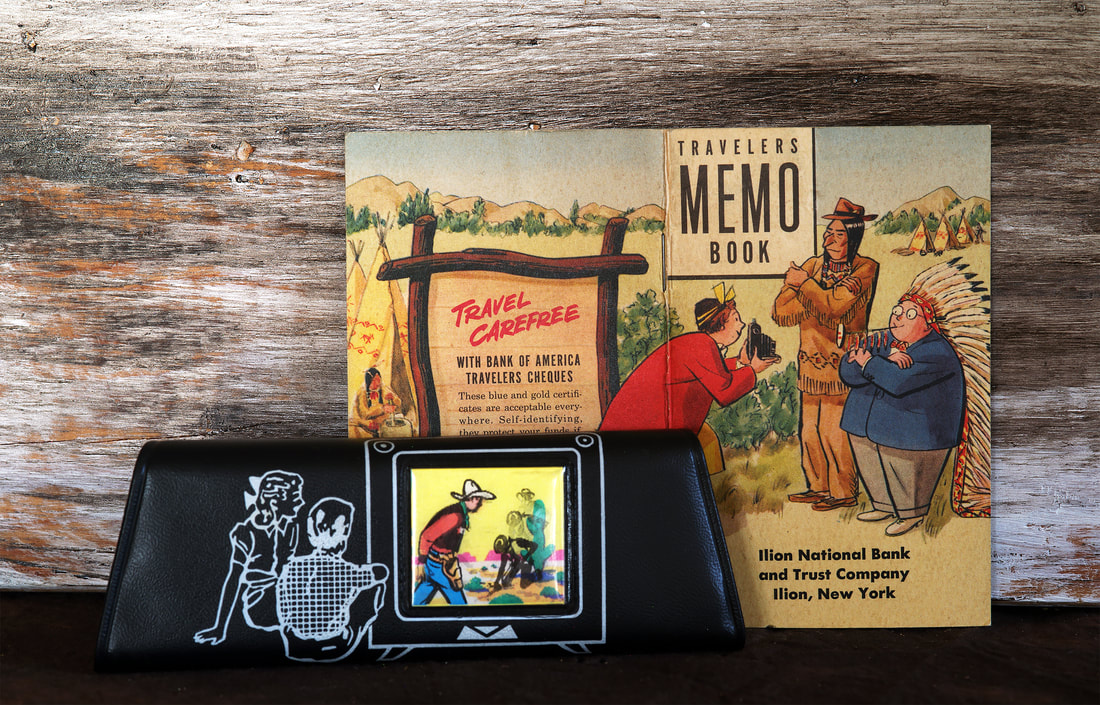

In many ways, art and direct action are not antithetical – since studying agricultural engineering in 1969, Ron Benner has been using his work to fight against industrial agriculture.

“I really just wanted to be a farmer, or work with farmers. That’s what I really wanted to do. I ended up being an artist because I had a lot more freedom and all of my friends were artists,” Benner explains. “I could have been an organic farmer, but I just really wanted to critique what I was up against when I was a young student.” Being part of an inherently flawed system, means moving outside of that system and working diligently to offer up alternatives in both theory and in praxis.

Through the infinite, prototypical possibilities of art – our attention is drawn to greater, more abstract questions surrounding the health of our environment. In Christina Battle’s ongoing work, seeds are meant to disperse she manages to share the gift of growing plants while simultaneously underlining how capitalism and economic fallibility play into this process. Through the barter and trade system utilized in her work (that is sometimes more about gift economies than equal exchange), there is a similar exchange transpiring between plants and humans. “I think people are really accustomed to thinking that they’re going to buy this seed pack and then it’s going to do this thing for them – and that is really not how plants or seeds work, they don’t work within the realm of capitalism,” says Battle – an important reminder for gardeners and artists alike.

Much in the way that contemporary art has developed parameters for critical work, so have humans adopted industrial and standardized processes for engaging with nature – processes that have ultimately shaped, and even distorted, our understanding of the environment. Rampant settler-colonialism and neoliberal ideology have imbued our relationship to nature with corrosive ideas; that nature is a resource to be claimed and profited from, and that any subsequent damage is the responsibility of an individual, not the system (who has coerced and mired the individual).

Across Turtle Island (so-called Canada), we now have the opportunity to learn from surrounding Indigenous cultures to consider traditional and practical ways of engaging with the Earth, and to work with Indigenous communities to embrace long-standing perspectives that put the wellness of the earth first. Niro outlines the monumental task for settlers and Indigenous communities alike, “Although we are sensitive to different things, you have to really put yourself in a position of trying to learn about what there is to do.” If we want any sort of change - it’s going to take all of us, artists included.

Many practitioners have already taken to this task, but artists assert that there is still work to be done. “I think we have to go beyond just acknowledging indigenous frameworks and ways of being – especially when it comes to food and land,” Battle says.

Ron Benner recalls how Indigenous perspectives have ultimately influenced his own values, and the work that he continues to do, “I believe in the public ownership of our food systems, of our water systems, because they’re for everyone and they shouldn’t be owned. That relates back a lot to Indigenous peoples around the world – who don’t believe in private ownership of things that are essentially necessities for us to continue to live.”

At the intersection of culture and community, art may be one of the greatest tools for drawing attention to environmental issues. As obvious or critical as it may seem, a collective and multi-faceted approach will be required to combat something as enormous and pressing as the challenges facing our environment today – whether it be as complex as soil erosion or as banal as plastic straws.

To enact an audience to care is to hold up a mirror, and to make clear the implications on existence, on human life, – and that is ultimately what art is good at (even if that doesn’t change the state of the world in one fell swoop). As something as old and innate as cave painting, art exercises a potential that embodies the meaning of what it means to be human, and more importantly, what it means to be alive in the world today. When there is so much at stake, the collective responsibility can feel both heavy and bleak. Shelley Niro feels the weight of the future alongside many others, but continues to work diligently:

“I like to think that I’m making work not to take people away from those thoughts but to give them something to think about, and to give them something to be hopeful for.”

To see more of Ron Benner’s work: http://www.ronbenner.ca

To see more of Christina Battle’s work : http://cbattle.com

To see more of Shelley Niro’s work: http://shelleyniro.ca

This article was originally published in Terra Observer, June 5, 2020.

Re-published and amended for Embassy Cultural House, April 22, 2021.