Year of Glass

The year 2022 was declared by UNESCO as the Year of Glass. In a publication marking the occasion, artists, glass scientists, and engineers write that it is possible to call our special moment in time as the Age of Glass.[1] We are where we are because of glass. Because of lenses that reveal both the microscopic biological world and telescopic universes beyond ours. Because glass can be made into sinewy fibres to power a global, digital network, and because glass can have a protective transparency allowing us to access the world through our television, computer, and phone screens.

As UNESCO celebrates the past, present, and future of glass, this project by the Embassy Cultural House is as an attempt to think of glass as medium and language. Like the spoken word, artisanal glass works too require human breath to manifest. But glass is also an antithetical material. It is both “medium and barrier.”[2] It is visibly invisible. As lenses, windowpanes, and digital screens, by allowing light to travel through it, glass makes visible another world. And by preventing air from entering and corrupting the spaces that it encases, glass can create the illusion of crystalized time. This project is a tribute to the stories that the unique malleability and materiality of glass makes possible to tell.

[1] Alicia Durán and John M. Parker, eds., Welcome to the Glass Age: Celebrating the United Nations International Year of Glass 2022 (Madrid: CSIC, 2022), 13.

[2] Armstrong, Isobel, Victorian Glassworlds: Glass Culture and the Imagination 1830-1880 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 11.

As UNESCO celebrates the past, present, and future of glass, this project by the Embassy Cultural House is as an attempt to think of glass as medium and language. Like the spoken word, artisanal glass works too require human breath to manifest. But glass is also an antithetical material. It is both “medium and barrier.”[2] It is visibly invisible. As lenses, windowpanes, and digital screens, by allowing light to travel through it, glass makes visible another world. And by preventing air from entering and corrupting the spaces that it encases, glass can create the illusion of crystalized time. This project is a tribute to the stories that the unique malleability and materiality of glass makes possible to tell.

[1] Alicia Durán and John M. Parker, eds., Welcome to the Glass Age: Celebrating the United Nations International Year of Glass 2022 (Madrid: CSIC, 2022), 13.

[2] Armstrong, Isobel, Victorian Glassworlds: Glass Culture and the Imagination 1830-1880 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 11.

Scot Slessor

Clearly Canadian

|

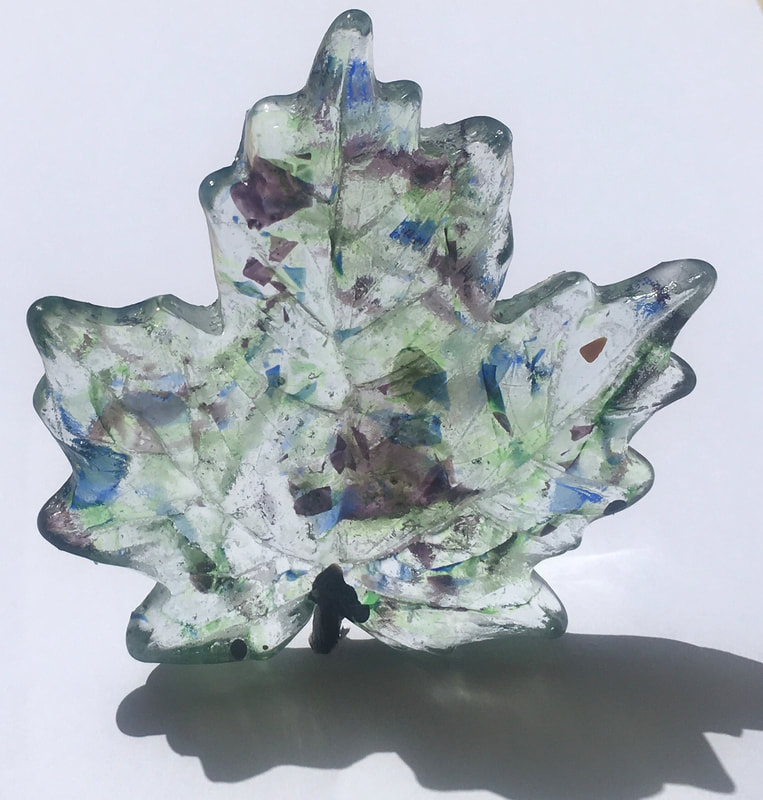

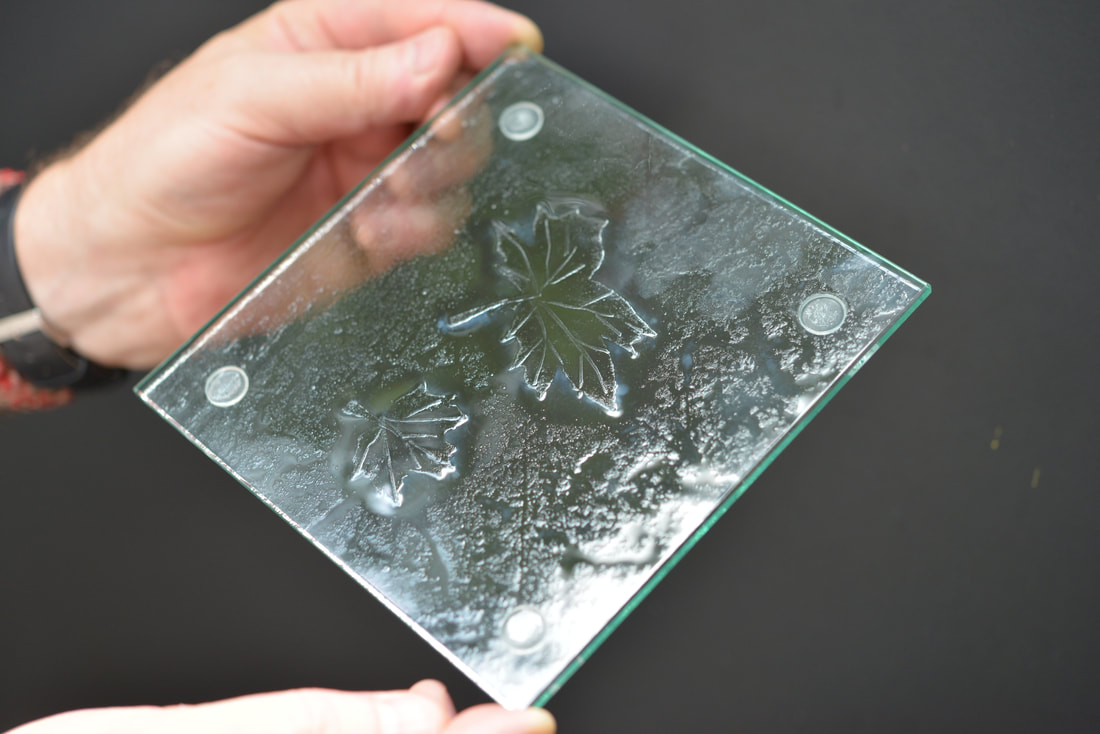

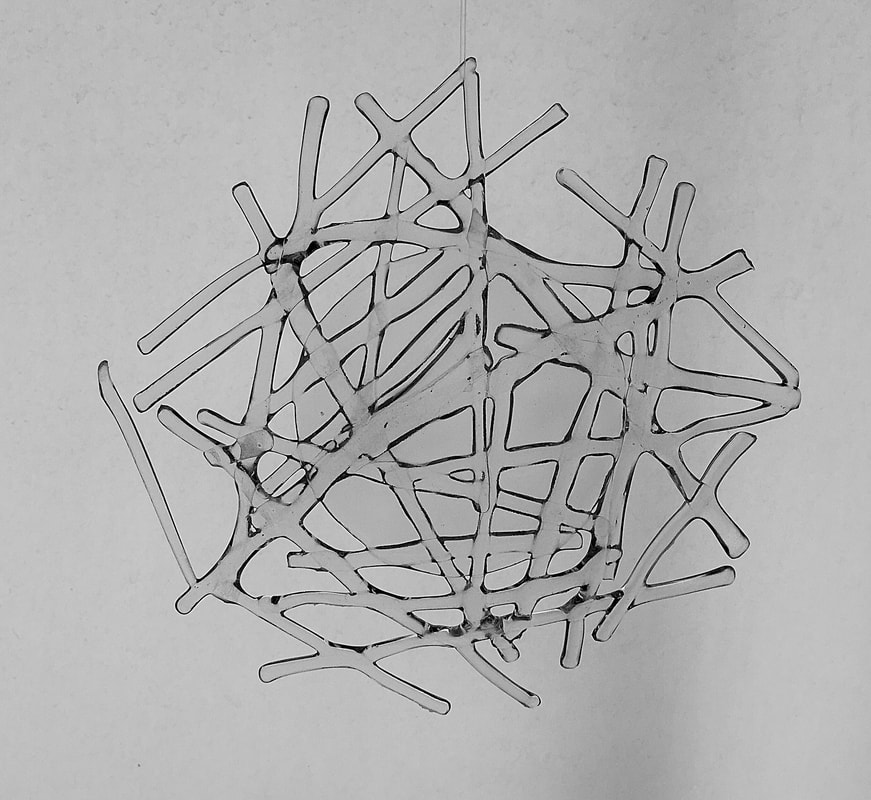

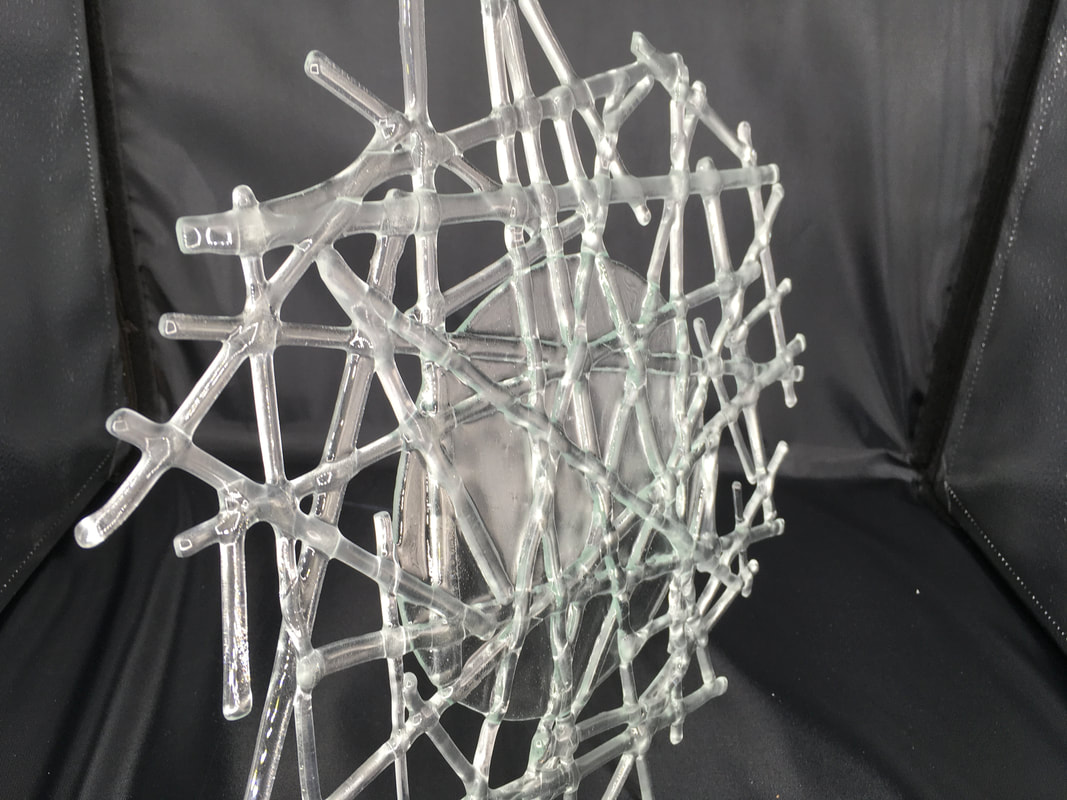

Sculptures from Scot Slessor's Clearly Canadian series. Slessor began this ongoing series in 2015.

|

As a child of the prairies, I spent many hours melting the frost on my bedroom window. Using my fingertips to melt frost between the valleys and mountains created naturally by air and slow, steady, freezing condensation. We lived outside when we were children. Winter was snow and ice with landscapes continually changing as snow fell, was ploughed, melted, and covered in another blanket.

Using clear, or white, float glass to etch maple leaves and other images brings me right back to that frosted window. I am still using heat, with the help of gravity, to shape my visual winks to the world.

Casted maple leaves allow me to replicate not only the clear frosty ice of my prairie window but also to explore the many gradations of the oceanside seasons that are now my home—reds and yellows and ocean blue and brown, when we know the water is warm, and the white of the main ingredient of glass, sand.

Glass, like snow, ice and water can be reshaped with heat and so I continue to explore new shapes and colours. I no longer have my fingertip on the window frost but rather on the panel of computerized kiln controller.

Using clear, or white, float glass to etch maple leaves and other images brings me right back to that frosted window. I am still using heat, with the help of gravity, to shape my visual winks to the world.

Casted maple leaves allow me to replicate not only the clear frosty ice of my prairie window but also to explore the many gradations of the oceanside seasons that are now my home—reds and yellows and ocean blue and brown, when we know the water is warm, and the white of the main ingredient of glass, sand.

Glass, like snow, ice and water can be reshaped with heat and so I continue to explore new shapes and colours. I no longer have my fingertip on the window frost but rather on the panel of computerized kiln controller.

Rebecca Baird & Kenny Baird

All Magic is in the Will

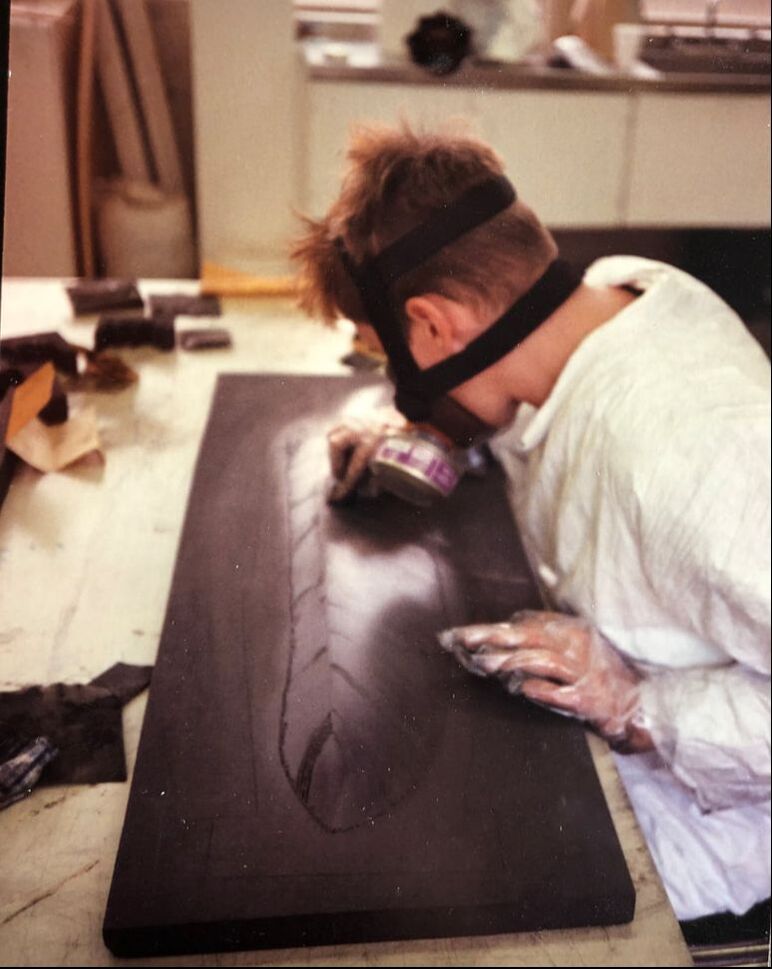

Rebecca Baird created All Magic is in the Will with her brother and collaborator Kenny Baird. Kenny carved the eagle feather design in the graphite which became the mold glass artist Alfred Engerer poured the glass to create the individual eagle feathers.

Engerer describes the process and the photos documenting it thus:

(top right) The mold—take note of the wall thicknesses in areas where heat loss is a great concern—the stem or quill end, the area where there is a protrusion into the feather body and finally the tip of the feather. The extra thickness of the mold walls in these areas creates a reservoir of heat and aids in the retention of heat in the glass in those areas. Graphite is one of a number of materials used in moldmaking for glass as an end product. Its greatest advantage is its machining with fairly simple hand tools, drills, saws, etc.

(2nd photo on the left) Kenny carving the eagle feather shape into the graphite mold.

(2nd photo on the right) Alfred Engerer and Andrey Berezowsky(?), a partner in The Outlaw Neon and also a partner in the formation of our co-op, Geisterblitz Glass Studio, pulling the molten glass from the kiln.

(3rd photo on the left) Maintaining a clean pour, while traveling over the length of the mold, is quite the task with the cumulative weight cantilevered away from my body. That's why in one shot Andrey (?) and I both have our hands on the ladle handle. The stem or quill was cast off a blow pipe after the pouring of the main body of the feather.

(3rd photo on the right) Andrey (?) trimming and clipping the excess glass from the lip of the ladle. This is done to ensure a clean pour of the glass. The glass in the ladle when full, weighs sixteen pounds. The ladle weight is about twenty pounds.

(bottom left and right) After both the main feather body and the stem have been cast, it is necessary to torch the three areas—the stem, the inset and the end of the casting. So, in addition to an extra thickness of mold walls, the torching of those areas is assisting in heat retention while the majority of the casting is allowed to naturally cool down through contact with the mold and the atmosphere of the room. It's kind of like dodging and burning when making a photographic print.

Marnie Fleming

Who Knew?! Finding William Morris in Fredericton

|

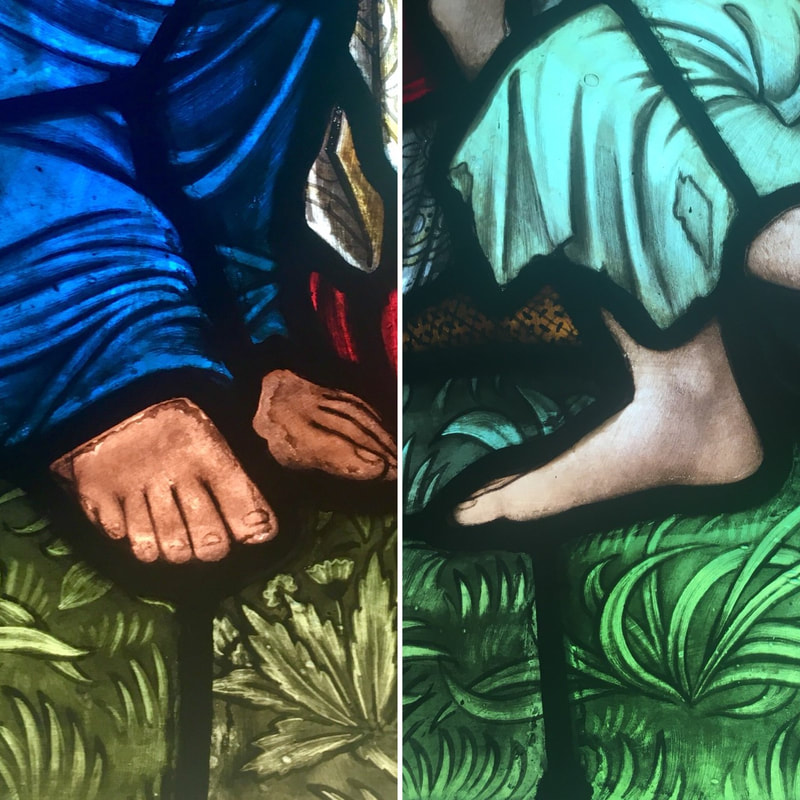

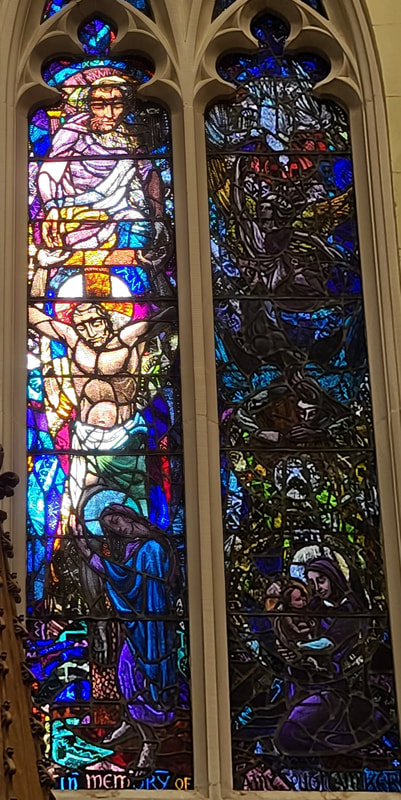

Stained glass window by William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and John Henry Dearle in Wilmot United Church, Fredericton, New Brunswick. Photographs by Marnie Fleming, 2022.

|

In June 2022, the Embassy Cultural House installed a billboard featuring artist’s projects from the exhibition, Pandemic Gardens: Resilience through Nature in Fredericton, New Brunswick. While there, our small group happened to come upon an extraordinary stained glass window in Wilmot United Church by British artists, William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and John Henry Dearle.

For years, the Wilmot window largely went unrecognized as being a Morris & Co. gem, until 1991 when it was finally authenticated by curators of the National Gallery of Canada. The curators, in preparing for a Morris exhibition, had come to Fredericton on a hunch (tipped-off by some paperwork) that they might just find the window at the church, and they did!

William Morris (1834–1896) and his followers, reacted against Britain’s increasing industrialization, to eventually become known as the Arts and Crafts Movement. Morris exerted an immense influence on the artistic and political developments of his time by leading a campaign to bring art to the people and to better social conditions. His movement called for an end to the capitalist division of labour, as machines soon began to replace workers. For inspiration, he and his followers looked back in history for craft-based alternatives, including stained glass windows and imagery. They believed that they could lead society out of its gritty squalor by creating beautiful objects with nature-inspired themes. This philosophy was both a social and artistic movement.

While in Fredericton, we learned that The Wilmot United Church window was shipped from the UK in 1912 and installed in 1913. It was a commission financed by New Brunswick Senator, Frederick Thompson for his daughter’s wedding. At that point both Morris and Burne-Jones had died but “the firm” of Morris & Co. (1875–1940) continued making windows using designs and cartoons that the two artists had created many years before. The hallmarks of the Morris & Co. artists can be seen in this window. For Burne-Jones, his signature style of attenuated angels and a passion for storytelling can be observed at the top of the window, while the lower intertwining acanthus leaves, were a frequent motif that Morris starting using in 1872. Morris’s successor and apprentice, John Henry Dearle designed the lower part of the window depicting two acts of mercy: feeding and clothing the poor. Such scrupulous details as the bare-footed poor are indicators of his skill and innovation. Following Morris’s death, Dearle was appointed Art Director of the firm, and became its principal stained glass designer upon the death of Burne-Jones in 1898.

This window was clearly the stand-out in the Fredericton church. It follows Morris’s 1890 dictum for stained glass declaring that: “The qualities needed in the design are beauty and character of outline; exquisite, clear, precise drawing of incident… Whatever key of colour may be chosen the colour should always be clear, bright, and emphatic.” The artists’ use of various greens in the Wilmot church window, particularly in the grass and foliage, demonstrate the Arts and Crafts philosophy: that humans desperately need a connection to nature to live a truly enriching life. Such details brought us back to our own contemporary moment and how Pandemic Gardens: Resilience through Nature can also provide an alternative way of looking at an unjust world, particularly in a moment of pandemic crisis.

Jamelie Hassan

Roman mosaics

|

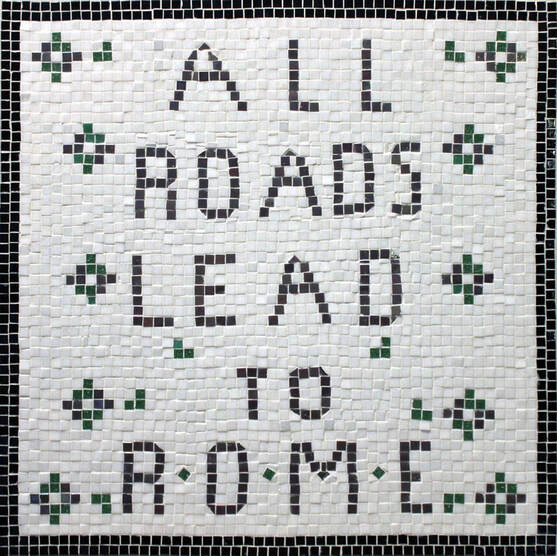

(Top left) All Roads Lead to Rome, 2022, glass mosaic tiles, (top right) mosaic in Pompeii, (bottom left) Rome ne fu pas toute en un jour (Rome was not built in a day), 2022, glass mosaic tiles, (bottom right) view of Vesuvius, photo taken by Jamelie Hassan in Februrary 2020.

|

When the COVID-19 pandemic tragically impacted the world, Ron Benner and I had travelled to Rome to rendezvous with family. With the increasingly alarming situation, our trip was cut short. But we managed, besides Rome, to visit Pompeii with its views of a smoking Mount Vesuvius. In retrospect, this trip with all its difficulties, was a catalyst for a number of mosaic works that reflect on the times I had spent in Rome and Italy. Upon our return and the initial months of the pandemic, my attention to my studio work was limited as we managed the reality of the lockdown and all the changes that were happening in our lives due to the crisis.

Over the years my research on glass mosaic tile work had taken me to many significant archaeological sites and museums in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. I had begun using glass mosaic tile as a medium in 2018 after completing a workshop with Indigenous artist Brenda Collins, who was known for her Medicine Wheel mosaic educational and cultural workshops. Having the chance to work in this medium suited me, as the work is all done in-studio and not dependent on outside technical support. I have a very direct relationship in the creation these works, though Ron often helps with the cutting of tiles and grouting the mosaic work once completed. It’s an enjoyable process. Some people see these pieces as “minor” works, while others have welcomed this shift in my practice. It’s true they are quiet artworks but I take the medium seriously. It requires focus and effort and is time-consuming but is often created in a spontaneous way without too much preliminary drawing or layout.

These mosaic works have been presented in exhibitions including: “Translations: Jamelie Hassan & Soheila Esfahani", Campbell River Art Gallery, Campbell River, BC, curated by Jenelle Pasiechnik, 2020; “GardenShip and State", Museum London, London, ON curated by Patrick Mahon and Jeff Thomas, 2021-2022; “A Roman Anthology" works gathered together by Janice Gurney, Birch Contemporary Gallery, Toronto, 2022.

All Roads Lead to Rome is the most recent work of these mosaic panels which have involved reflections on Rome and various texts which are common expressions and parables. According to the Cambridge Dictionary the idiom is said to mean that “all methods of doing something will achieve the same result in the end."

Also of significance is this proverb's origins which “may relate to the Roman monument known as the Milliarium Aureum, or Golden Milestone, erected by Emperor Caesar Augustus in the central forum of ancient Rome. All distances were measured from this point, and it was regarded as the site from which all principal roads diverged" (Quoted from the Centre for Italian Studies for the exhibit All Roads Lead to Rome, 2011).

Rome Ne Fu Pas Faites Toute Ene Un Jour (Rome was not built in a day), this parable reflects the original language which was in medieval French, circa 1190. It's meaning is that patience is needed to create and that one can not rush a task to do it properly.

Ron Benner

As the Crow Flies

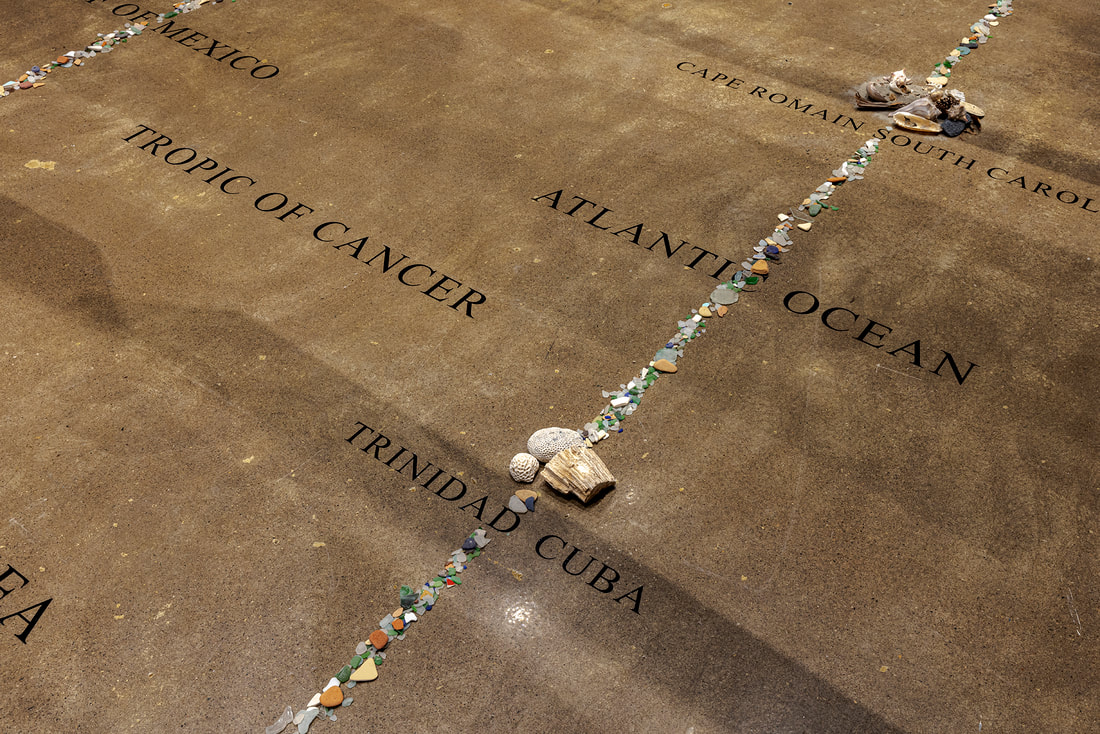

As the Crow Flies, 1984-1991, mixed media photographic installation. Photo credit: Tony Hafkenscheid. From the exhibition GardenShip and State, Museum London, 2021.

As The Crow Flies (1984-1991) is a mixed media photographic installation in the collection of the McIntosh Gallery, Western University, London, Ontario. The work documents what is due south of London and Toronto, Ontario, where large bodies of water are encountered. The two lines of longitude on the floor are represented by ‘cultural deposits' collected from the shoreline of Lake Erie by the artist and friends over a period of 8 years. The deposits consist of glass, ceramic and metal sherds which over the years were smoothed by the action of the waves against the sand of the shoreline. These deposits have gradually disappeared with the advent of plastic and aluminum containers. Nowadays, one is hard-pressed to find any beach glass at all.

Wyn Geleynse

An Imaginary Situation With Truthful Behaviour and Glass Tree House

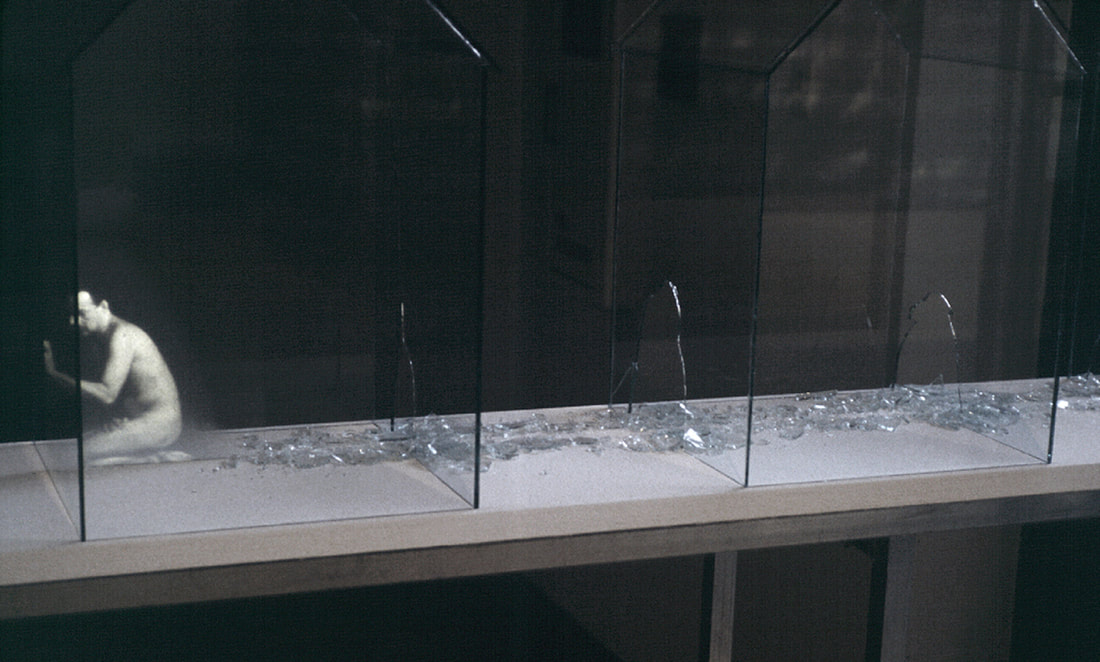

(Top) An Imaginary Situation With Truthful Behaviour, 1998, nine glass houses approximately 18" x 12" x 12" each, and 16mm looped film projection. (Above) A detail from An Imaginary Situation With Truthful Behaviour. From the exhibition Northern Noises.

Photos courtesy: Wyn Geleynse.

Photos courtesy: Wyn Geleynse.

|

(Left) Glass Tree House, 2020, 18" x 9" x 9". Glass, wood, silicone, modelling paste.

|

In the mid 1980s, I started to play with rear-projecting 16mm film loops onto ground glass, and did a number of pieces using a constructed glass house with a rear-projection inside, onto the glass sheet that I would selectively grind in order to intercept the image that I wanted to have appear. These early pieces dealt with domestic images of interpersonal relationships and economics.

In late 1987 or early 1988, I was asked to do a work for the 1988 Winter Olympics for an exhibition called Northern Noises in Calgary, AB. The resultant piece is the one illustrated above, entitled An Imaginary Situation With Truthful Behavior. It consisted of nine glass houses approximately 18” x 12” x 12” aligned in a row. Three of the houses were outside of the NOVA Chemicals building and six were inside, parallel to the employees entrance. Projected into the first house outside on the first day of the exhibition is a naked man, on his knees scratching furiously on the inside wall facing the rest of the houses, mimicking the path the employees would take entering the building. Every three days he would break through the wall into the next house, leaving a trail of broken glass through the tunnel of holes he created, until the end of the exhibition trapping him in the last house. Since then, I have created a number of iterations of my glass house icons, including sculptural diaristic installations housing multiple objects or simple structures inside these transparent containers, and various types of tree houses, the last as illustrated here. |

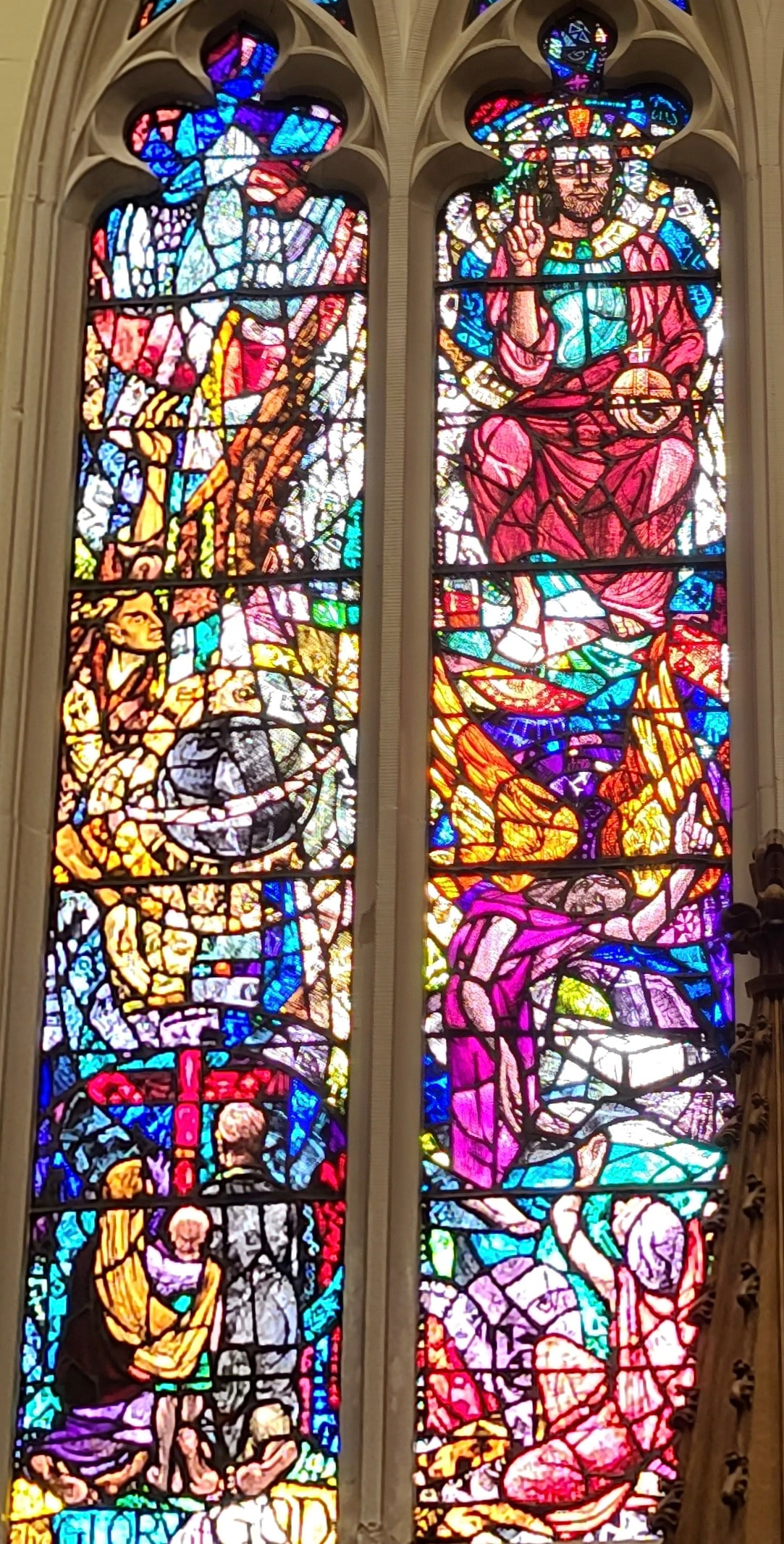

Yvonne Williams’s Priscilla and The Great Christian Festivals

Text by Iraboty Kazi

Photographs by Iraboty Kazi and Anahí González. Project by Iraboty Kazi and C. Cody Barteet.

A leader, educator, and one of the first women to establish her own career in the male-dominated practice of twentieth-century Canadian stained glass, Yvonne Williams (1901-1997) forged a distinct and influential style that contributed to the development of modern stained glass in North America. She produced over 400 stained glass windows across the country and mentored numerous successful stained-glass artists.

An important element of her work that deserves more research is her depiction of people of colour in her windows, including The Great Christian Festivals at Christ's Church Cathedral, Hamilton, St. Michael at Holy Trinity, Welland, Priscilla at St. John the Evangelist, London, and the Call of Peter and Andrew at St Jude’s, Oakville. Some windows, like the lower panel of the Priscilla and Her Majesty's Royal Chapel of the Mohawks in Brantford, include indigenous figures in relation to the subject, location, or patronage. For example, the Inuit figure opening a box in the lower panel of the Priscilla window references the work of the Women’s Auxiliary of the Missionary Society of the Anglican Church of Canada who knitted, quilted, and made garments for the missions in the Northwest Territories and India. However, in windows, such as Christ's Church Cathedral, Hamilton, ON, she deliberately chose to portray religious figures as racialized people. Needless to say, this is a departure from the historically inaccurate but typical portrayal of Jesus and the Holy family as Caucasian. Her childhood in the multicultural Trinidad and her later interest in African sculpture may have played a role in her desire to depict people of colour in her works. While it is difficult to ascertain her motivations, it adds another layer of complexity and sets her apart from others in her field.

Throughout her illustrious career, she brought attention to stained glass as a medium for expressing the ideas of contemporary society. Williams’ work ranges from figurative and representational subjects for religious sites (the Resurrection window in St. Michael’s and All Angels, Toronto) to more abstract environmental-based works for secular and private buildings (St. Bernard’s Hospital, Toronto).{1} Regardless of the subject or the location, Williams maintained her high standards and experimented with abstract designs and colours.

An important element of her work that deserves more research is her depiction of people of colour in her windows, including The Great Christian Festivals at Christ's Church Cathedral, Hamilton, St. Michael at Holy Trinity, Welland, Priscilla at St. John the Evangelist, London, and the Call of Peter and Andrew at St Jude’s, Oakville. Some windows, like the lower panel of the Priscilla and Her Majesty's Royal Chapel of the Mohawks in Brantford, include indigenous figures in relation to the subject, location, or patronage. For example, the Inuit figure opening a box in the lower panel of the Priscilla window references the work of the Women’s Auxiliary of the Missionary Society of the Anglican Church of Canada who knitted, quilted, and made garments for the missions in the Northwest Territories and India. However, in windows, such as Christ's Church Cathedral, Hamilton, ON, she deliberately chose to portray religious figures as racialized people. Needless to say, this is a departure from the historically inaccurate but typical portrayal of Jesus and the Holy family as Caucasian. Her childhood in the multicultural Trinidad and her later interest in African sculpture may have played a role in her desire to depict people of colour in her works. While it is difficult to ascertain her motivations, it adds another layer of complexity and sets her apart from others in her field.

Throughout her illustrious career, she brought attention to stained glass as a medium for expressing the ideas of contemporary society. Williams’ work ranges from figurative and representational subjects for religious sites (the Resurrection window in St. Michael’s and All Angels, Toronto) to more abstract environmental-based works for secular and private buildings (St. Bernard’s Hospital, Toronto).{1} Regardless of the subject or the location, Williams maintained her high standards and experimented with abstract designs and colours.

|

(Above) Yvonne Williams, Priscilla, 1974, stained glass window, St. John the Evangelist, London, Ontario. Photograph: Anahí González

The Great Christian Festivals (1954) The four-panel window depicting the Nativity, the Crucifixion, Easter, and Pentecost is located in the chancel, on the left side of the altar. This is the last window to be added to the church and it stands out from the others due to its difference in style and composition. Moreover, this work exemplifies Williams’ representation of biblical figures as people of colour. This reoccurring motif can be seen throughout her works, including St. Michael at Holy Trinity, Welland, and the Call of Peter and Andrew at St Jude’s, Oakville.[3] The object at the bottom of the photograph is the peak of the canopy over the cathedral. The window was donated by the former managing director of the Hamilton Spectator and later publisher, Frederick Innis Ker (1884 - 1981) in memory of his wife, Amy Southam Ker (1896 - 1942).[4] The window was restored during the summer of 2020. Sandy explains: “In 1977, plexiglass was installed to protect all windows but for those on the south side this built up heat so the lead softened and the glass flowed down with the force of gravity. All the south-facing windows of the nave and the east window have been restored.”[5] (Above) The Great Christian Festivals, the Nativity and Crucifixion panels, Christ's Church Cathedral, Hamilton. Photograph: Iraboty Kazi

Easter The third panel with an angel over the empty tomb, and God above presides over the events of Easter. Williams’ unique use of colours and thicker glass creates the illusion of texture within the darker lines and lighter patches of colour, like the red cloak, which adds more to the rich colours. Pentecost The final scene is the coming of the Spirit at Pentecost. Pentecost was the day the disciples were no longer afraid, and the church was founded. After the crucifixion, the disciples were confused and dispirited. Even after learning on Easter Sunday morning that Jesus had risen, they met that evening in an upstairs room, because they were afraid. Later they went to Galilee but were back in Jerusalem by the time that spirit came to them (Acts 2). Darling states: “I believe that the central image is God with His world. The family at the bottom represents the church, and at the tops is the Holy Spirit coming to God’s earth.” |

Priscilla (1974)

Dedication: “To All Who Served in the W.A., 1889 – 1967” “Mirror, Mirror Hanging on the wall, which is the Fairest Window of Them All?” The Priscilla Window stands out in the church due to Williams’ abstract geometric design and jewel-like colours. In the window, Priscilla holds a strip of purple cloth and a needle. Along with her husband, Aquila, she was among the earliest of the Christian converts. They are referenced at least six times in the New Testament. They were tentmakers and Paul lived and worked with them. They represent Christian cooperation, hospitality, and service. Further, there is academic speculation that Priscilla wrote the Book of Hebrews, which is considered to be the only book of the New Testament without an author. The window commemorates the service of devoted women of the church. According to Spicer, lower panel highlights the work of the Women’s Auxiliary of the Missionary Society of the Anglican Church of Canada, which started in this church’s parish in 1889.[2] Their weekly meetings coupled spirituality with knitting, quilting, and making garments for the missions in the Northwest Territories and India. (Above) Yvonne Williams, The Great Christian Festivals, 1954, stained glass window, Christ's Church Cathedral, Hamilton. Photograph: Iraboty Kazi

The Nativity In the Nativity scene on the right Mary and Jesus are at the foot of the window with an angel above them. The Crucifixion (Good Friday) Jesus is shown on the cross with his mother, Mary, at the foot, and God above. Sandy Darling, the writer of “Christ’s Church Cathedral,” who generously provided me a tour of the church, states: “To my untrained eye, there are three characteristics that make this window different: the glass is thicker so that it is best seen in sunlight before 2:00 p.m., the palette of colors is much richer, and the glass has texture, unlike some of the flat colors of the other windows nearby.”[6] (Above) The Great Christian Festivals, the Easter and Pentecost panels, Christ's Church Cathedral, Hamilton. Photograph: Iraboty Kazi

|

[1] Helena Kuprosky, “50 Years of Modern Work," Canada Crafts, Oct/Nov 1978, 25.

[2] Elizabeth Spicer, Trumpeting Our Stained Glass Windows. London: St. John the Evangelist, 2008, #19.

[3] Alexander (Sandy) L. Darling, A Visual Tour of Christ’s Church Cathedral, Hamilton, Ontario, (Hamilton: Christ’s Church Cathedral, September 2020), 30.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

Click to visit the project Yvonne Williams: Life and Work of an Influential Stained Glass Artist.

[2] Elizabeth Spicer, Trumpeting Our Stained Glass Windows. London: St. John the Evangelist, 2008, #19.

[3] Alexander (Sandy) L. Darling, A Visual Tour of Christ’s Church Cathedral, Hamilton, Ontario, (Hamilton: Christ’s Church Cathedral, September 2020), 30.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

Click to visit the project Yvonne Williams: Life and Work of an Influential Stained Glass Artist.