Hotels, Posadas, Pensioni

Coordinated by Andy Patton with the assistance of Olivia Mossuto

Artists often don’t get rich but they live rich lives, a friend once told me. Travel forms part of that rich life: artists often travel to exhibitions and for research. Both take them far afield. Often this takes them to places a more conventional life would not have carried them.

While writers are routinely associated with hotels, we thought it might be interesting if artists and writers associated with the Embassy Hotel wrote of some of the more interesting hotels where they had found themselves. This, we hope, might eventually produce an eccentric map of the world travelled by those who circled around the ECH, a map not just of different nations but of different locales and different cultural micro-climates.

While writers are routinely associated with hotels, we thought it might be interesting if artists and writers associated with the Embassy Hotel wrote of some of the more interesting hotels where they had found themselves. This, we hope, might eventually produce an eccentric map of the world travelled by those who circled around the ECH, a map not just of different nations but of different locales and different cultural micro-climates.

Michael Baker

The Sunnyside Hotel, London, CanadaThe Embassy Hotel had already been a London East landmark for almost 50 years when the Embassy Cultural House opened in one of its side rooms in 1983. For decades it was home to many east-enders and was a popular neighbourhood bar almost from the time it opened as the Sunnyside Hotel in 1936.

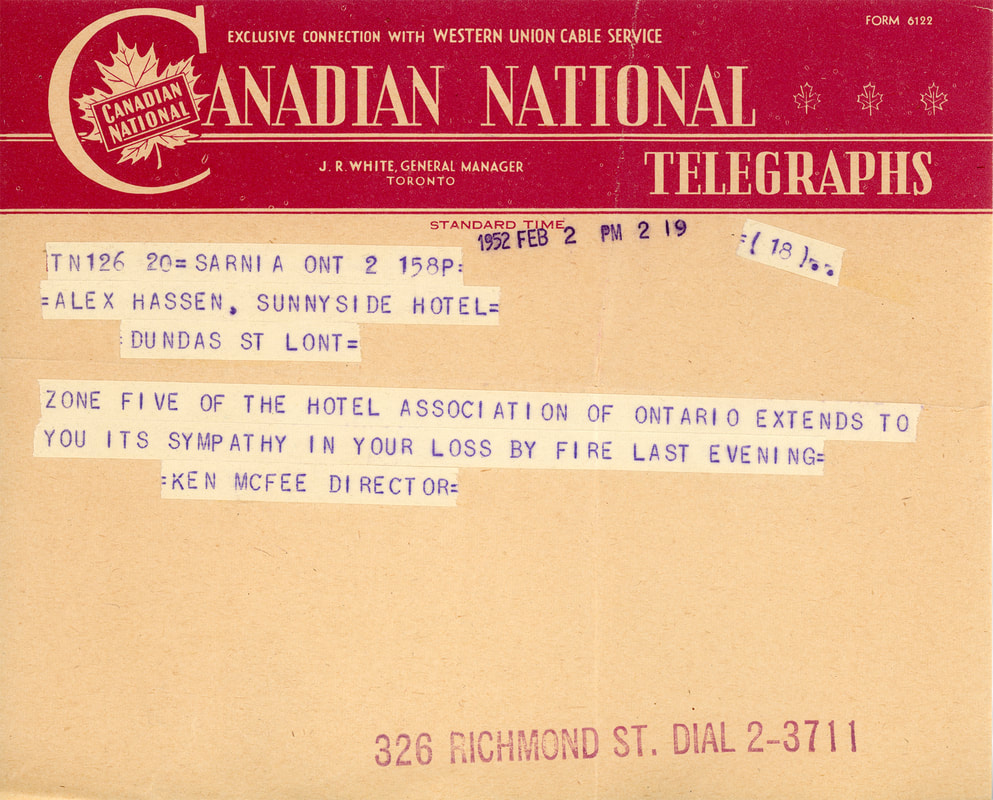

Its location at 732 Dundas, between English and Elizabeth Streets, put it at the centre of East London’s thriving commercial centre. Along with the rest of the street, the hotel, once a pair of semi-detached homes, slowly evolved from a 44-room hotel into the permanent residence of a few long-time tenants. The restaurant and bar remained popular gathering places until it closed in 2009. The building was destroyed by fire in May of 2009. The slate-shingled roofs of two substantial double houses were always visible over the top of the rug brick facade of the Embassy. Built around 1910 these homes were comparable to the house that still stands opposite the Palace Theatre at 707 Dundas. Among the first occupants of 730-32 Dundas was Chester Stevens, a future chairman of EMCO, still one of the country’s largest plumbing supply companies, whose factory was one of the first to appear in London East. Before World War I London East was a small self-contained city. Kellogg’s, EMCO and McCormick were all operating, having been drawn east to the location of a new connecting track or “interswitch” between the country’s two national railways, whose workshops and yards formed the north and south boundaries of the community. Between them lived hundreds of clerks, factory hands and artisans with a variety of shops and services lining both sides of Dundas from Adelaide to Rectory. Dundas between Elizabeth and English Streets were still largely residential in 1910, although a tailor named Watson and a butcher named Brooks had already moved into the houses west of 730-32 Dundas. Others would soon follow as the commercial district expanded. The building of the Palace Theatre in 1929, which replaced the mansion built by the English family, the area’s original land owner, was a clear indication that the neighbourhood had changed for good. Another sign of change was the conversion of 730-32 Dundas into apartments in 1932, likely undertaken by Alex Hassan, an immigrant from Lebanon who had come to London just before the outbreak of World War I. In the 1920s, Hassan established three successful grocery and fruit stores, all located on the north side of Dundas Street - one on the corner of Ridout, one near the corner of Adelaide, and one on the corner of English. The conversion of 730-32 was likely caused by the Depression during which many large houses were converted in response to a demand for cheaper housing. Hassan may have been the one who named the new apartment building the “Sunnyside” after the popular song of the day. The 1930s also brought the return of the beer hall. The decision to license “beverage rooms” in Ontario in 1934 sparked a flurry of activity in the city’s hotel industry. To obtain a license, separate rooms and entrances were required for “men” and for “women and escorts.” This initiated considerable remodelling of the city’s existing hotels. It was in this context that the Sunnyside Apartments were converted into the Sunnyside Hotel. Alex Hassan had always wanted to open a hotel and by 1936 the timing appeared right. He purchased the neighbouring double house on Dundas (734-36) and combined them into a single building through an extension built out to the street line, clad in red rug brick with precast details Trained as a stonemason in Lebanon, Alex Hassan did much of the construction and design work himself. The hotel opened in 1936 as a 44-room hotel with beverage rooms on the ground floor. It was also home to the Hassan family. During a trip back to Lebanon in 1938 Alex married Ayshi Shousher and brought her to live in an apartment in the hotel. Four of the couple’s 11 children were born in the apartment. Ayshi Hassan recalls seeing newsreels and films at the nearby Palace Theatre and their doctor, Dr. Henry, living nearby in a house with a separate entrance to the office. In 1944, the family moved to 26 Erie Avenue. Business was good and in late 1951 the hotel was renovated and enlarged. A fire in February of 1952 extensively damaged the newly expanded beverage rooms delaying the reopening. The fire also exacerbated a financial problem and Alex Hassan decided to sell in 1957. Brothers Alfred and John Vassar bought the business while Hassan retained ownership of the building along with several other adjacent properties he had acquired over the years. It was at this time that the hotel’s name was changed to the Embassy and in 1963 a new restaurant, the Embassy Room, opened. The hotel returned to the Hassan family in 1977 when Alex Hassan’s daughter Helen and her husband Egon Haller bought it. They set about renovating the property as it had deteriorated somewhat over the years. The hotel’s bar had a large number of regulars, at least one of whom had been stopping in since it first opened. One of the projects initiated by the Hallers was the commissioning of a set of portraits of some of the hotel’s regulars and several long-time staff. Helen’s sister Jamelie Hassan created the portraits saying at the time that she learned a lot about the hotel’s history and that of her family. In the 1980s, when the Embassy Cultural House occupied the restaurant, “(t)he 40-room, 65-dollar-a-week hotel was a constantly changing space where bar regulars, off-duty taxi drivers and hotel residents mixed with artists and concert-goers, creating a living and evolving community within its walls.”(1) The Embassy also became known for the local, national and international bands that appeared there offering everything from country and western to punk and jazz. |

|

___

(1) Christopher Regimbal, “A Fire at the Embassy Hotel,” Fuse magazine, Volume 33 Issue 3, September 2010.

(1) Christopher Regimbal, “A Fire at the Embassy Hotel,” Fuse magazine, Volume 33 Issue 3, September 2010.

Excerpted from the original essay “A Stop at the Sunnyside: The Sunnyside/Embassy Hotel Story" with permission of the author, Michael Baker. The essay was published in the catalogue, The Embassy Cultural House: 1983 - 1990, for the survey exhibition curated by Bob McKaskell at Museum London in 2012, which is available on the ECH website.

Jeff Thomas

The Executive Motor Hotel, Toronto, Canada

I made this photo of the Travelodge in 2006 and, having recently rediscovered the file, it brought back so many memories of my early trips to Toronto. I had returned many times and usually for a meeting and always to make new images of the city. I lived in Toronto from 1983 to 1986, and when I left for Winnipeg in 1986, I was hoping to find the inspiration I had lost while living in Toronto.

While I was in Toronto, I photographed my then seven-year-old son Bear on Queen Street West in 1984, a time when I was frustrated making the transition from my hometown of Buffalo, New York, to Toronto. I was having a difficult transition because Toronto was so different from Buffalo, where I began my career photographing the post-industrial trauma experienced in the downtown area of the city. Many of the staple businesses that had been there since the early 20th century were being crushed by the arrival of suburban shopping malls and the collapse of the steel industry. I had a very challenging time finding the same landscape in Toronto.

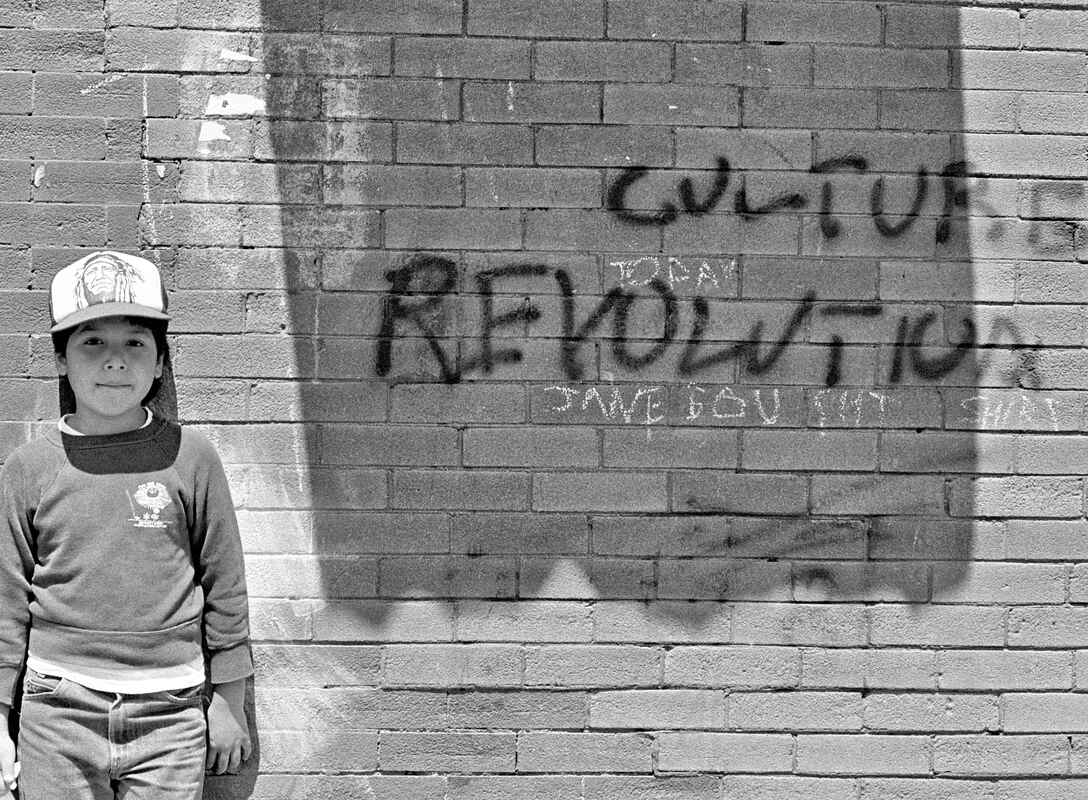

In 1984 I had taken Bear to the Silver Snail on Queen Street West to buy comic books. When we finished and crossed the street to return to my car, I saw a brick wall tagged with “Culture Revolution.” I posed Bear next to the wall and the casual street portrait would become a career changing image. I realized that if I was going to capture the city as I felt it as an Indigenous person, I could not simply respond to what already existed. I began instead to think of ways to intervene from an Indigenous point of view.

Although thousands of Indigenous people lived in Toronto at the time, they were largely invisible in the everyday world. On the day I posed Bear, I wondered how long we would have to stand there until we saw another Indigenous person walk by.

After moving to Winnipeg in 1986, I did discover a way to at least begin the process of intervention. When I moved from Winnipeg to Ottawa, I began making more and more trips to Toronto. I had asked a friend to recommend an inexpensive hotel in Toronto and he told me about the Executive Motor Hotel on King Street West near Bathurst. Many artists stayed here because it was cheap and there was free parking.

It was a great location and the people who worked behind the desk were always nice to me and addressed me by my name when I checked in. One of the things I did not like about Toronto was how quickly sections of the city were changing and I hoped that the Executive would never change. It was fun to enjoy good chicken wings at the corner restaurant, the Banknote, watch people head home after work, and see the crowded street cars ramble by. It was near perfection when a Second Cup opened on the opposite corner. It was a great place to sit in the morning and do some writing with coffee and a muffin.

Yet, over time I began seeing the street change. The Executive was sold and rebranded as the Travelodge, although the people that had become my friends were still working there. I remember that ominous day in 2009 when I checked in and my friend told me they would be closing soon and he would be transferred to the Travelodge off Highway 401. I started staying at the Delta Hotel on subsequent trips but it would never be the same; the luster of staying in Toronto had vanished under the façade of new development.

One day while walking along Chippewa Street in Buffalo I photographed a barber shop, a very unique place with all the amenities that had probably been there since the 1940s. I returned another day hoping to talk to the barber. But the building had been demolished and the only visible sign was the #11 on the door frame that still stood upright in the debris.

When I drive past the place where the Executive once stood, I felt a great sense of loss. Sometimes I wonder if that is why I love making photographs – to capture memories of a world that moves and changes too fast.

While I was in Toronto, I photographed my then seven-year-old son Bear on Queen Street West in 1984, a time when I was frustrated making the transition from my hometown of Buffalo, New York, to Toronto. I was having a difficult transition because Toronto was so different from Buffalo, where I began my career photographing the post-industrial trauma experienced in the downtown area of the city. Many of the staple businesses that had been there since the early 20th century were being crushed by the arrival of suburban shopping malls and the collapse of the steel industry. I had a very challenging time finding the same landscape in Toronto.

In 1984 I had taken Bear to the Silver Snail on Queen Street West to buy comic books. When we finished and crossed the street to return to my car, I saw a brick wall tagged with “Culture Revolution.” I posed Bear next to the wall and the casual street portrait would become a career changing image. I realized that if I was going to capture the city as I felt it as an Indigenous person, I could not simply respond to what already existed. I began instead to think of ways to intervene from an Indigenous point of view.

Although thousands of Indigenous people lived in Toronto at the time, they were largely invisible in the everyday world. On the day I posed Bear, I wondered how long we would have to stand there until we saw another Indigenous person walk by.

After moving to Winnipeg in 1986, I did discover a way to at least begin the process of intervention. When I moved from Winnipeg to Ottawa, I began making more and more trips to Toronto. I had asked a friend to recommend an inexpensive hotel in Toronto and he told me about the Executive Motor Hotel on King Street West near Bathurst. Many artists stayed here because it was cheap and there was free parking.

It was a great location and the people who worked behind the desk were always nice to me and addressed me by my name when I checked in. One of the things I did not like about Toronto was how quickly sections of the city were changing and I hoped that the Executive would never change. It was fun to enjoy good chicken wings at the corner restaurant, the Banknote, watch people head home after work, and see the crowded street cars ramble by. It was near perfection when a Second Cup opened on the opposite corner. It was a great place to sit in the morning and do some writing with coffee and a muffin.

Yet, over time I began seeing the street change. The Executive was sold and rebranded as the Travelodge, although the people that had become my friends were still working there. I remember that ominous day in 2009 when I checked in and my friend told me they would be closing soon and he would be transferred to the Travelodge off Highway 401. I started staying at the Delta Hotel on subsequent trips but it would never be the same; the luster of staying in Toronto had vanished under the façade of new development.

One day while walking along Chippewa Street in Buffalo I photographed a barber shop, a very unique place with all the amenities that had probably been there since the 1940s. I returned another day hoping to talk to the barber. But the building had been demolished and the only visible sign was the #11 on the door frame that still stood upright in the debris.

When I drive past the place where the Executive once stood, I felt a great sense of loss. Sometimes I wonder if that is why I love making photographs – to capture memories of a world that moves and changes too fast.

Olivia Mossuto

Kashiwaya-Ryokan, Saku-Nakagomi, Nagano, Japan

In June of 2018, my dad passed away from an aggressive bout of Lymphoma that had appeared in his pelvis and metastasized without warning. In June of 2019, I spent eight or nine days at Kashiwaya-Ryokan in Saku, a small city located in the Nagano prefecture of Japan. My trip to the semi-rural town was borne out of the desire to create distance from a continuing period of grief. I sought to isolate myself in a place that was as far as possible from the site of trauma. What I had learned, very quickly, was that the insular motivations of my emotions had negated my ability to consider that I would not be alone, and that I would be busy catching beetles and making pizza.

What I first noticed at Kashiwaya was the long basin and row of taps that stretched along the hall directly to the right beyond the sliding door to my room. The bathroom was a large shared room on the main level lined with faucets and stools to sit while you shower. There were no ensuite bathrooms, as is common of ryokans (traditional, Japanese-style inns). A once personal morning routine became a communal experience. My bedroom was furnished with tatami mat and a low table, accompanied by a simple futon on the floor. In the shared kitchen, I would improve upon the few recipes I worked with since the beginning of my stay in Japan. Every morning I made banana-matcha oatmeal and for dinner, soba noodles with soft tofu and squash.

After the first morning, I met Mayumi and her son Haku while I was brushing my teeth. I learned that the guesthouse primarily hosted long-term tenants and I was living among neighbours. I met another tenant named Kairi, who was introduced to me through Mayumi. They shared every kindness and local interest that was available in Saku. Mayumi would take me on car trips to interesting landmarks and would bring me along to the park, where Haku and his friend, Kazu, would go bug-catching. The moms would watch, and I would do the running and the chasing. Kairi brought me to the local art gallery and museum, and accompanied me to a hot spring after I had expressed interest in visiting one day. One night, I was invited by some tenants to a social event hosted at the ryokan. I am not sure if there was an occasion, but I was welcomed for the food and good company. Dinner consisted of skewered meat and vegetables over a charcoal grill, and personal pizzas; wood-fired pizza cooked entirely by Kazu in a handmade clay oven, no bigger than two feet.

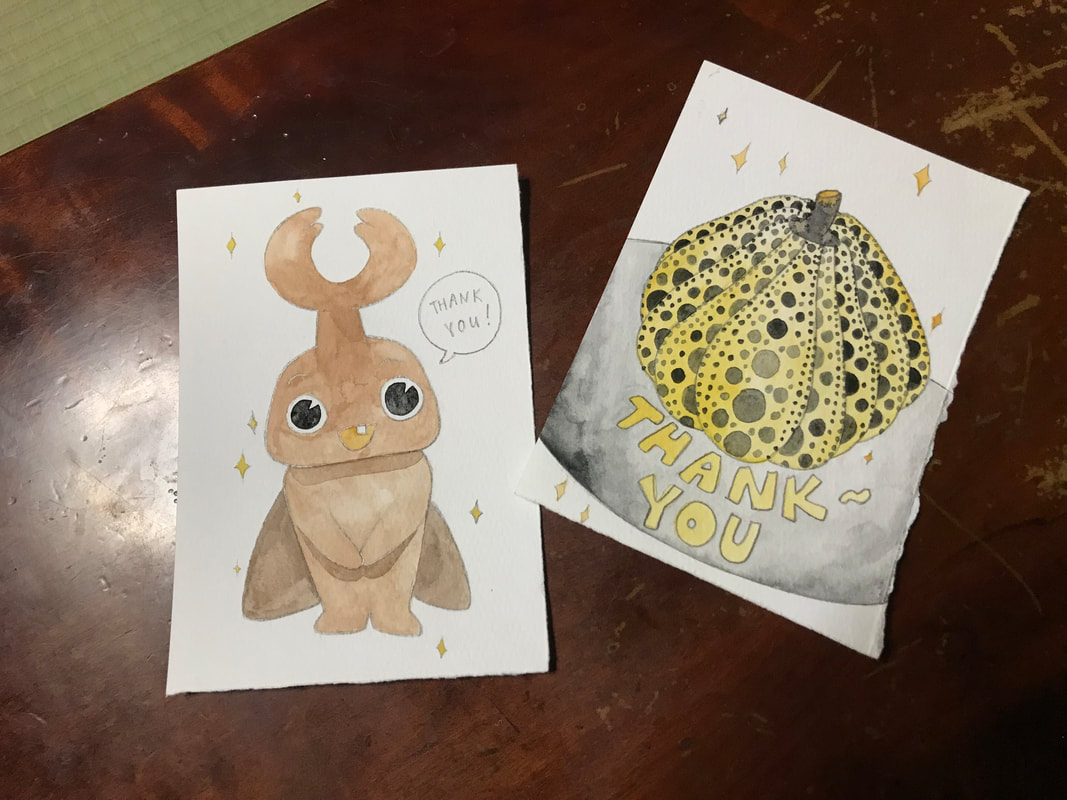

On the day that would have been Father’s Day in 2018 (June 17) I went walking for hours. I passed rice paddies and suburban farms. I began drawing cards to thank Mayumi, Haku and Kairi on my last day. It was the only day that I was alone, and it was only because I had closed the door to my room.

What I first noticed at Kashiwaya was the long basin and row of taps that stretched along the hall directly to the right beyond the sliding door to my room. The bathroom was a large shared room on the main level lined with faucets and stools to sit while you shower. There were no ensuite bathrooms, as is common of ryokans (traditional, Japanese-style inns). A once personal morning routine became a communal experience. My bedroom was furnished with tatami mat and a low table, accompanied by a simple futon on the floor. In the shared kitchen, I would improve upon the few recipes I worked with since the beginning of my stay in Japan. Every morning I made banana-matcha oatmeal and for dinner, soba noodles with soft tofu and squash.

After the first morning, I met Mayumi and her son Haku while I was brushing my teeth. I learned that the guesthouse primarily hosted long-term tenants and I was living among neighbours. I met another tenant named Kairi, who was introduced to me through Mayumi. They shared every kindness and local interest that was available in Saku. Mayumi would take me on car trips to interesting landmarks and would bring me along to the park, where Haku and his friend, Kazu, would go bug-catching. The moms would watch, and I would do the running and the chasing. Kairi brought me to the local art gallery and museum, and accompanied me to a hot spring after I had expressed interest in visiting one day. One night, I was invited by some tenants to a social event hosted at the ryokan. I am not sure if there was an occasion, but I was welcomed for the food and good company. Dinner consisted of skewered meat and vegetables over a charcoal grill, and personal pizzas; wood-fired pizza cooked entirely by Kazu in a handmade clay oven, no bigger than two feet.

On the day that would have been Father’s Day in 2018 (June 17) I went walking for hours. I passed rice paddies and suburban farms. I began drawing cards to thank Mayumi, Haku and Kairi on my last day. It was the only day that I was alone, and it was only because I had closed the door to my room.

Oliver GirlingThe Hotel Vista Hermosa Taboada, San Miguel de Allende, Mexico

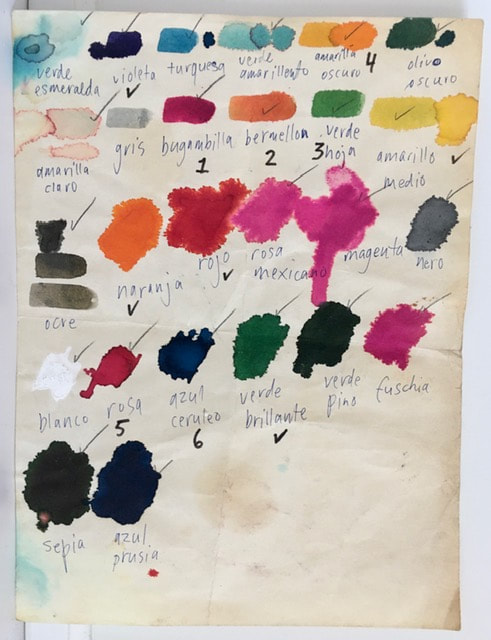

In the rolling Sierra Madre foothills north of Mexico City, there’s a rambling, red brick dowager of a hotel, in a street off the Zocalo in the town of San Miguel d’Allende: The Vista Hermosa Tabuada. I started staying there in the ‘Nineties, in a room on a second floor terrace overlooking a Jacaranda grove, whose bright blue petals carpet the hillsides for a solid week in February. At the other end of the building, and of the pallette, ever-blooming, red bougainvillea spill over the sidewalk and surround the arch at the street entrance to Cuna de Allende, No. 11. At about 10:30 in the morning the gringos shuffle down the perilous stairs from the third floor to the terrace, having saluted the sun in their top level studio. At midday, a young man from the water company arrives with 10 gallon jugs on cradle/rockers, provided to each suite for drinking and cooking (the dirty sluice down the hill having ceased to be potable years ago). In the evening, incredible shouting from the grackles in the trees of the Zocalo competes to drown out the traffic din, shoe-shiners compete for business (dusty shoes in Mexico being thefirst sartorial sin) and Mexicans and gringos alike step out to see the people and catch scent of the square’s dazzling flowers before they close. My parents, inveterate winter travellers, discovered first the town, then the hotel, and introduced me to it a few years later. Such was its allure that they left their favourite destinations- Bagni di Lucca, Shrinagar, The Lake District, Aix-en-Provence, Madeira, to make it their seasonal pied-a-terre. It has historical and natural interest: the Mexican revolution began here; the Monarch butterfly over-wintering ground is at Michoacan, just up the highway. Both Mexicans and North Americans have congregated since the Thirties, for the art school, symphony orchestra, nightly entertainment, galleries, and restaurants which serve a subtle version of Mexican cuisine not so well known to the world. David Siquieros, muralist and mentor to Pollock and Guston, taught at the art school, and began (but never finished) a mural whose starting cartoons can still be seen in the building. Diego Rivera was born nearby in Guanajuato, since reinvented as an all-pedestrian town by diverting its motor traffic into an early, now obsolete, vast system of sewer pipes. The mysterious, socialist novelist B.Traven (“The Treasure of the Sierra Madre”) spent time here, it’s said- I can see him scribbling in one of the uncomfortable, cast-iron lattice chairs in the San Miguel library courtyard. The hotel walls are clad in irregular. square ceramic tiles from the neighbouring factory town of San Luis Potosí. Their milky-patina’d, solid colours are used in bathrooms and shower stalls, giving way to the serial patterning and arabesques on the stairs and colonnades; designs adapted by the Spanish from the Moors, and now given a Mexican spin. I make pictures in ink, sitting on the sunny terrace and painting the view, using the most brilliant, liquid colours I’ve ever found (called, counter-intuitively, Rodin)- manufactured somewhere in the country, but that I can only source here. By the early Millenium, my parents were gone, and I stopped going. The ‘naughties and ‘teens were hard for the hotel, as well as for the town of San Miguel, caught in the crossfire between gang violence, drug turf-wars and official corruption. By 2011, it had been sold to condominium interests. But as other small cities (like Sudbury) have discovered, not everyone responds to that siren song. To my joy, I see that since 2017 it’s a hotel again, no longer Tabuada but Selina San Miguel de Allende Hotel. If it manages to weather the pandemic, if we all do, I’ll go back again to enjoy that country of everyday wonders, to that city of criminality and creativity, and its beautiful, welcoming bohemian refuge. |

Yam Lau

Hotel Bonaventure, Montréal, Québec, Canada

For some reason, the Hotel Bonaventure (1) in Montréal lingers in my memory, mostly distantly and vaguely, but occasionally it registers. It is a bit of a mystery that I cannot quite account for, especially when I have never stayed there. Recently, this once iconic, but now outmoded hotel once again surfaces in my awareness. I made plans for a visit, but I never went.

…a Childhood

The story begins in the 70’s Hong Kong, where I was born and lived until I came to Canada at fifteen. I grew up with a single mother. We were poor and isolated, had no telephone for some years. The small room we lived in was suffused with my mother’s sadness. It felt even smaller still. I remember seeing her tears rolling down in silence, often in the late afternoon light. Then gradually, during this prosperous decade that rewarded hard work, household items, all essentials taken for granted today, began to appear one after another. Phone, TV, fridge….The washing machine was the last and came much later. At ten years old, in 1976, my mother and her partner had saved enough money to travel abroad. My mother and I left for the US and Canada. It was a tremendous experience and a big deal for me.

Why Montréal? It was because we knew a friend from Hong Kong there. Mr. Andrew Poon. Going two years back, it was around 1974 when I first met him as a boarder, renting a room in our apartment in HK. He originally came from the Southern part of mainland socialist China, and like many young, capable men of his generation, escaped to Hong Kong for opportunities. I recall him as young, strong, handsome and savvy. A worldly man who worked in the booming film industry. He decorated his room with a special green wall finish, which was a rare luxury at the time. As we lived in the same apartment, I would see him daily. Mr. Poon was friendly, and soon he became a sort of big brother/hero type of figure. Being the only child growing up in a confused and difficult “family” situation, my early years were almost entirely spent in solitude and I had almost no social life. Mr. Poon’s friendship provided a great source of solace.

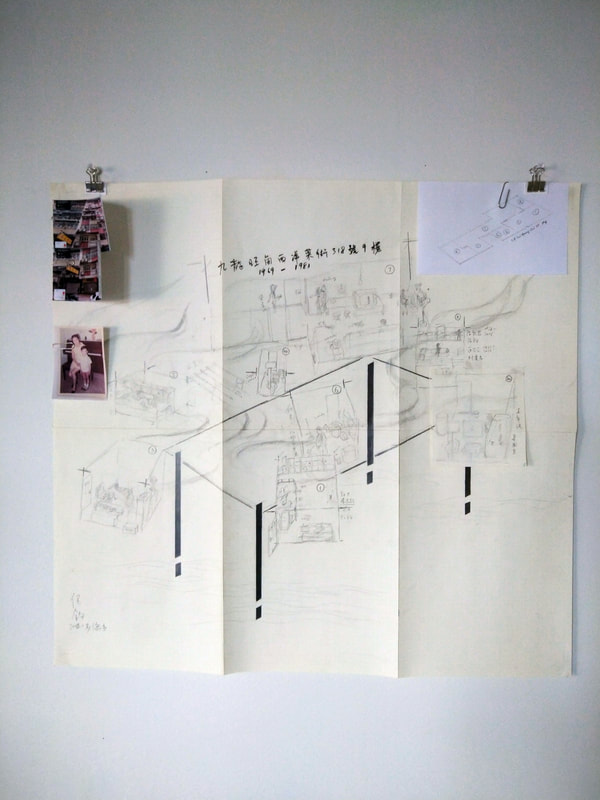

Recently, I made a drawing from memory, in which I recalled and traced out my apartment (fig 2), the layout, the furniture, and certain events in tentative, uncertain lines. I remember a lot of incidents, some minor, some traumatic, that involved Mr. Poon. At eight years old, I witnessed a stabbing in the living room. Frightened, I banged on Mr. Poon‘s door crying for help. He stepped out to mediate and stop the assault. I still remember the exact words and his pleading tone that late evening. Another incident involved the authorities who came looking for him. I learned that he was implicated in a case of theft and my mother and her companion at the time alerted him about the police‘s visit. As a result, he was able to destroy some material evidence and was never charged. That was the only time policemen entered my home. Mr. Poon boarded with us for a couple of years then immigrated to Canada, where his girlfriend would later join him. The morning Mr. Poon left HK for Montreal, he left a goodbye note. I still remember the exact words in the first sentence “怱怱而別對不起”, “apologies that I left in such hurry”. He remained a friend of the family in Montreal. Upon arrival he sent us a long note “於xx 平安底達滿地可”, “on xx (a date) I safely arrived in Montréal”. We kept regular correspondence by letters. People seemed to value friendship deeply back then.

In 1976, my mother and I arrived in Montreal after visiting the US west coast and Vancouver. We were hosted by Mr. Poon and his girlfriend in his modest apartment located in the Nuns’ Island (I only figured this out recently), a sort of suburb of Montréal. We arrived in time to catch the closing ceremony of the 1976 Olympics. I was introduced to pizza, cornflakes…

… the hotel lobby

Once we took the train to visit Mr. Poon’s workplace in downtown Montreal. It was the lobby of the Hotel Bonaventure. I am not sure if I was slightly disappointed or embarrassed that my “hero” was a bellman. In any case, the scene in which he came towards us pushing his trolley lodged in my memory. Reality is not an easy place to be, and I wondered if he saw his immigrant dreams compromised. Later, Mr. Poon relocated to Edmonton, Alberta, hoping to take advantage of the oil boom economy. This is the reason why my mother and her partner, Mr. Pang, chose Edmonton when they immigrated in 1982. There is a Chinese proverb “出外靠朋友”, “when you travel, you depend on your friends”.

…. Mr. Poon, in later years

Prior to coming to Canada, Mr. Pang and my mother had been seeing each other in HK clandestinely for a few years. It was an affair as they both had other partners and families. The decision to come to Canada together is a decisive break, a clean slate of sorts from their former lives in HK. We purchased a townhouse in Edmonton, in the same complex as Mr. Poon and his family. In the beginning, the two families were close, and Poon offered tremendous help for us newbies. As Mr. Pang was a well-known chef (2) and Poon had been a bartender, they ventured into the restaurant business. But I observed that Mr. Poon was often distraught, and later learned that he was in a lot of debt. He appeared deflated and defeated, a stark contrast with my impression of him in HK. In fact, he was still wearing the some clothes from almost a decade ago. My family loaned him money to cover his debt. Then, their businesses failed and there was a fallout. From what I know, he never paid back the loan. Since that time, around 1987, I have never seen him again. It was equally heartbreaking that my mother and Mr. Pang never enjoyed a happy moment in Canada. They both suffered deeply in a relationship fraught with anger and resentment. At times, I even doubted the sanity of my mother. Perhaps it is a blessing that both have left this world. I pray for their peace.

I often wonder what happened to Mr. Poon’s two children, how they turned out in what I surmised was a difficult environment (their parents separated). I was able to see the profile of one of them on FB for a brief period. But the past has become too distant for me to make any contact.

So, the Hotel Bonaventure. Around this bit of memory seems to thread a life. Looking back at fifty-six, it seems that is indeed how I "got" here. Life seems like a fluke. I don’t know if there is meaning in these events of pain, trauma, but also moments of joy. I wonder if all of these are a mere mixture of pure luck and misfortune. I wonder how Mr. Poon sees this life now, or if the Hotel Bonaventure has any significance for him. “That too is as it is in each heart”, said the abbess Satoko in Mishima’s “The Decay of Angels”.

It seems almost everyone in the story has lost their bet, in Canada.

Yam Lau

Toronto

19 September 2021

____

(1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Place_Bonaventure

(2) My mother also had years of restaurant experience. In fact, she met Mr. Pang at their workplace.

…a Childhood

The story begins in the 70’s Hong Kong, where I was born and lived until I came to Canada at fifteen. I grew up with a single mother. We were poor and isolated, had no telephone for some years. The small room we lived in was suffused with my mother’s sadness. It felt even smaller still. I remember seeing her tears rolling down in silence, often in the late afternoon light. Then gradually, during this prosperous decade that rewarded hard work, household items, all essentials taken for granted today, began to appear one after another. Phone, TV, fridge….The washing machine was the last and came much later. At ten years old, in 1976, my mother and her partner had saved enough money to travel abroad. My mother and I left for the US and Canada. It was a tremendous experience and a big deal for me.

Why Montréal? It was because we knew a friend from Hong Kong there. Mr. Andrew Poon. Going two years back, it was around 1974 when I first met him as a boarder, renting a room in our apartment in HK. He originally came from the Southern part of mainland socialist China, and like many young, capable men of his generation, escaped to Hong Kong for opportunities. I recall him as young, strong, handsome and savvy. A worldly man who worked in the booming film industry. He decorated his room with a special green wall finish, which was a rare luxury at the time. As we lived in the same apartment, I would see him daily. Mr. Poon was friendly, and soon he became a sort of big brother/hero type of figure. Being the only child growing up in a confused and difficult “family” situation, my early years were almost entirely spent in solitude and I had almost no social life. Mr. Poon’s friendship provided a great source of solace.

Recently, I made a drawing from memory, in which I recalled and traced out my apartment (fig 2), the layout, the furniture, and certain events in tentative, uncertain lines. I remember a lot of incidents, some minor, some traumatic, that involved Mr. Poon. At eight years old, I witnessed a stabbing in the living room. Frightened, I banged on Mr. Poon‘s door crying for help. He stepped out to mediate and stop the assault. I still remember the exact words and his pleading tone that late evening. Another incident involved the authorities who came looking for him. I learned that he was implicated in a case of theft and my mother and her companion at the time alerted him about the police‘s visit. As a result, he was able to destroy some material evidence and was never charged. That was the only time policemen entered my home. Mr. Poon boarded with us for a couple of years then immigrated to Canada, where his girlfriend would later join him. The morning Mr. Poon left HK for Montreal, he left a goodbye note. I still remember the exact words in the first sentence “怱怱而別對不起”, “apologies that I left in such hurry”. He remained a friend of the family in Montreal. Upon arrival he sent us a long note “於xx 平安底達滿地可”, “on xx (a date) I safely arrived in Montréal”. We kept regular correspondence by letters. People seemed to value friendship deeply back then.

In 1976, my mother and I arrived in Montreal after visiting the US west coast and Vancouver. We were hosted by Mr. Poon and his girlfriend in his modest apartment located in the Nuns’ Island (I only figured this out recently), a sort of suburb of Montréal. We arrived in time to catch the closing ceremony of the 1976 Olympics. I was introduced to pizza, cornflakes…

… the hotel lobby

Once we took the train to visit Mr. Poon’s workplace in downtown Montreal. It was the lobby of the Hotel Bonaventure. I am not sure if I was slightly disappointed or embarrassed that my “hero” was a bellman. In any case, the scene in which he came towards us pushing his trolley lodged in my memory. Reality is not an easy place to be, and I wondered if he saw his immigrant dreams compromised. Later, Mr. Poon relocated to Edmonton, Alberta, hoping to take advantage of the oil boom economy. This is the reason why my mother and her partner, Mr. Pang, chose Edmonton when they immigrated in 1982. There is a Chinese proverb “出外靠朋友”, “when you travel, you depend on your friends”.

…. Mr. Poon, in later years

Prior to coming to Canada, Mr. Pang and my mother had been seeing each other in HK clandestinely for a few years. It was an affair as they both had other partners and families. The decision to come to Canada together is a decisive break, a clean slate of sorts from their former lives in HK. We purchased a townhouse in Edmonton, in the same complex as Mr. Poon and his family. In the beginning, the two families were close, and Poon offered tremendous help for us newbies. As Mr. Pang was a well-known chef (2) and Poon had been a bartender, they ventured into the restaurant business. But I observed that Mr. Poon was often distraught, and later learned that he was in a lot of debt. He appeared deflated and defeated, a stark contrast with my impression of him in HK. In fact, he was still wearing the some clothes from almost a decade ago. My family loaned him money to cover his debt. Then, their businesses failed and there was a fallout. From what I know, he never paid back the loan. Since that time, around 1987, I have never seen him again. It was equally heartbreaking that my mother and Mr. Pang never enjoyed a happy moment in Canada. They both suffered deeply in a relationship fraught with anger and resentment. At times, I even doubted the sanity of my mother. Perhaps it is a blessing that both have left this world. I pray for their peace.

I often wonder what happened to Mr. Poon’s two children, how they turned out in what I surmised was a difficult environment (their parents separated). I was able to see the profile of one of them on FB for a brief period. But the past has become too distant for me to make any contact.

So, the Hotel Bonaventure. Around this bit of memory seems to thread a life. Looking back at fifty-six, it seems that is indeed how I "got" here. Life seems like a fluke. I don’t know if there is meaning in these events of pain, trauma, but also moments of joy. I wonder if all of these are a mere mixture of pure luck and misfortune. I wonder how Mr. Poon sees this life now, or if the Hotel Bonaventure has any significance for him. “That too is as it is in each heart”, said the abbess Satoko in Mishima’s “The Decay of Angels”.

It seems almost everyone in the story has lost their bet, in Canada.

Yam Lau

Toronto

19 September 2021

____

(1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Place_Bonaventure

(2) My mother also had years of restaurant experience. In fact, she met Mr. Pang at their workplace.

Janice GurneyThe Buchan Hotel, 1906 Haro Street

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada In 1986, David MacWilliam asked me if I would like to teach the fall term at Simon Fraser University. It was a wonderful chance to spend 3 months in Vancouver so I agreed. Now Andy and I had to find a place to stay. We could not find any short term rental apartments. Airbnb did not yet exist. I can’t remember how we heard about the Buchan Hotel. Built in 1926, it was an inexpensive long-term rental hotel and the location was great. We lived in a sparsely furnished room with a bathroom and a large closet. We could not cook in the room so we either had to pick up food and bring it back to our room or go to one of the many restaurants nearby. I remember getting lots of take-out sushi. We ate chicken at St.Hubert’s where Andy eyed the lemon yellow Dino Ferrari parked out front. On Denman we bought shrimp and avocado sandwiches topped with bean sprouts. And we spent time in the little Italian coffee spot just next door. There was also a German restaurant with a separate entrance in the lower part of the Buchan. We sometimes went there for schnitzel or a reuben sandwich. The now-defunct Buchan Hotel still has an on-line presence. It is described as “an economically priced 3 story walk-up hotel ideal for travelers seeking clean, quiet, and comfortable accommodation. The Buchan Hotel is located in a residential area of Vancouver's downtown West End, one block from Stanley Park, and three blocks from English Bay Beach.” My mother came from Winnipeg to visit us for a week. She stayed in a room just down the hall from us. The Buchan was just right for everything we needed to have. Almost every day Andy and I would walk down Haro to the south end of Stanley Park. We watched the ducks on the Lost Lagoon. In the evening we would walk along the beach at English Bay. Almost every morning I would watch the sun rise into a clear sky. Almost every day it would rain. I bought a silver rain jacket and almost got used to living in Vancouver. In June 2020 the Province, through B.C. Housing, purchased the 63-room Buchan Hotel to provide housing for women in need. The site was empty, and residents began moving into the Buchan in July. Atira Women's Resource Society operates the housing at the hotel, which includes access to services such as meals, health care, addiction treatment and harm reduction, as well as storage for personal belongings. The site has 24/7 staffing to provide security to residents of the building and the surrounding neighbourhood. |

Ron Benner

Posada Margarita, Calle Abasolo, Oaxaca, México

My education began at the age of 23 when I first travelled to northern México in 1972 and again in 1974 when I stayed for a month in an unnamed residencia in Mexico City, south of Avenida Insurgentes and Paseo de la Reforma, across from a funeral home with caskets in the front window...shades of the artist José Guadalupe Posada.

Most of my fellow residents were Chilean political refugees who had fled the coup d'etat of September 11, 1973, orchestrated by General Augusto Pinochet and the CIA, against the elected socialist government of Salvador Allende. After obtaining numerous visas I headed south into Central and South America.

I have stayed in many hotels since that time but one of the most memorable was a 3 month stay in the family-run Posada Margarita, Oaxaca, México in 1992/93. The Margarita had originally been a doctor's residence and clinic. Colonial architecture defined the ground floor while two 'modern' rooms were located on the roof at the back. Jamelie and I rented one of the two upstairs rooms. Nothing fancy. Four metres by four metres. Our own bathroom. Two single beds which we moved together. A mirrored bureau. A desk. It became our studio. We were in walking distance to three libraries. The librarian, Freddy Aguilar, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, founded by Francisco Toledo, became a good friend and source for information on cochineal and indigo which I was researching. From our terrace was a view north to the Santo Domingo church and monastery, where a family of owls made their home, and facing east, the morning sun.

We did a lot of work. We learned a lot. Valío la pena.

Most of my fellow residents were Chilean political refugees who had fled the coup d'etat of September 11, 1973, orchestrated by General Augusto Pinochet and the CIA, against the elected socialist government of Salvador Allende. After obtaining numerous visas I headed south into Central and South America.

I have stayed in many hotels since that time but one of the most memorable was a 3 month stay in the family-run Posada Margarita, Oaxaca, México in 1992/93. The Margarita had originally been a doctor's residence and clinic. Colonial architecture defined the ground floor while two 'modern' rooms were located on the roof at the back. Jamelie and I rented one of the two upstairs rooms. Nothing fancy. Four metres by four metres. Our own bathroom. Two single beds which we moved together. A mirrored bureau. A desk. It became our studio. We were in walking distance to three libraries. The librarian, Freddy Aguilar, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, founded by Francisco Toledo, became a good friend and source for information on cochineal and indigo which I was researching. From our terrace was a view north to the Santo Domingo church and monastery, where a family of owls made their home, and facing east, the morning sun.

We did a lot of work. We learned a lot. Valío la pena.

Michael Spence

Hotel María Cristina, Mexico City

|

I have stayed at a lot of hotels in Mexico City over the years, some of them very nice and some not, but two in particular stand out in my mind, and my heart. The Hotel María Cristina is a lovely old traditional hotel built in 1937. Only a block from the Paseo de la Reforma, it is an oasis of calm in the centre of that huge bustling city. I loved to sit out in the large lawn with a bottle of Negra Modelo and a book. At times my wife Jean and my two daughters Tanya and Cassy stayed there with me, so there are memories there too. And the restaurant served the best Carne Asada a la Tampiqueña that I have ever tasted.

The other hotel is not so lovely, a concrete and glass American-style hotel with none of the character of the María Cristina. I can’t even remember its name. But I had a wonderful experience while I stayed there, one that coloured all my subsequent years in Mexico. |

I came to the hotel in 1963, at the age of 22, on my very first day in Mexico. I spent only one night there, leaving the following day to join a team working in the ancient city of Teotihuacan. In the evening I went for a walk, and several blocks from the hotel I came upon a cantina. It was full of people, talking and drinking, but I managed to find a spot at the bar. People started talking to me and I used my high school Spanish to carry on several rather erratic but enjoyable conversations. When I finally had to leave, hours later, my new friends told me that the area was dangerous at night, so a large group insisted on walking me back to the hotel. I knew then that I would love Mexico.

On the recommendation of this contribution by Michael Spence, Marnie Fleming, who recently joined the ECH's Advisory Circle spent a few nights at the Hotel María Cristina and took this dramatic photograph of the interior staircase. Thank you Marnie!

On the recommendation of this contribution by Michael Spence, Marnie Fleming, who recently joined the ECH's Advisory Circle spent a few nights at the Hotel María Cristina and took this dramatic photograph of the interior staircase. Thank you Marnie!

Jamelie Hassan

The Embassy Hotel, Beirut, Lebanon

I usually stayed at the Canadian-owned Mayflower Hotel in the Hamra area of Beirut when visiting the city. During the war years, the Embassy of Canada had moved into the Mayflower Hotel and had observed from its windows the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982. Tariq had arrived before me and spotted the Embassy Hotel in Hamra, and the name was obviously a magnet for him. Both hotels are centrally located and within walking distance to many landmarks including the legendary Khayat's Bookstore across from the campus of the American University of Beirut. A visit to Habib Abujaudeh, the owner of the bookstore who had become a friend, was one of the highlights I was looking forward to again and the chance to introduce Tariq to this bookstore and its owner. Habib was an incredibly knowledgeable person to discuss the political machinations that plagued the region and the news of the day.

It was a few days after 9/11 when Tariq and I met up in Beirut. Tariq was based in Cairo at the time working as a journalist and I was in Tirana, Albania attending the first Art Biennial that was in collaboration with the Italian journal Flash Art. The shocking news of the attacks in the USA totally eclipsed this inaugural cultural event on the very margins of the art world, with international artists and curators cancelling their trips to Tirana and those already in the city frantically booking the first possible flights out. All flights to North America had been cancelled.

Tariq and I had decided not to cancel our trip and to carry on with our plans to meet-up. When I managed to get a flight to Beirut there was a feeling of anxiety and foreboding in the city, with the fear that some location in the Muslim world would be attacked in retaliation. When I caught up to Tariq, he was going off to do an interview. While we had travelled together in the Middle East previously when my son was much younger, this was our first time in Lebanon together - the home country of my parents and his grandparents.

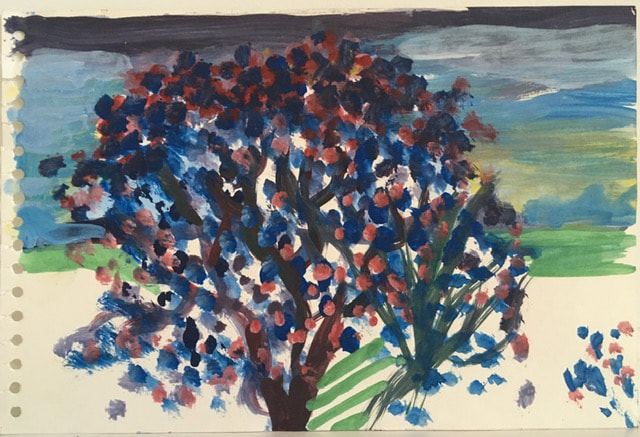

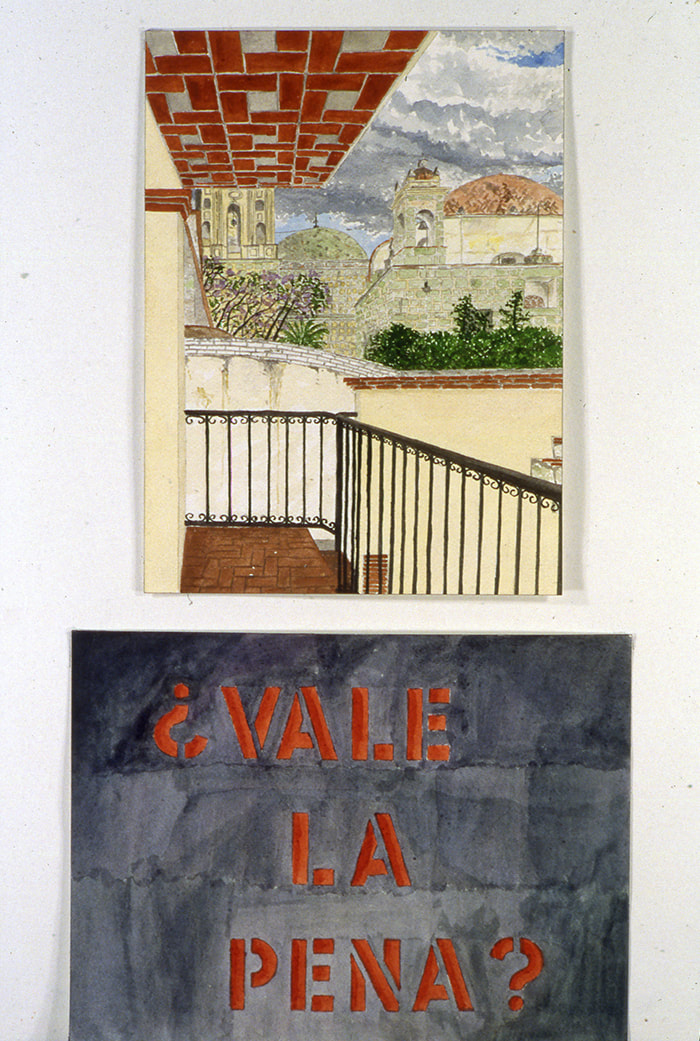

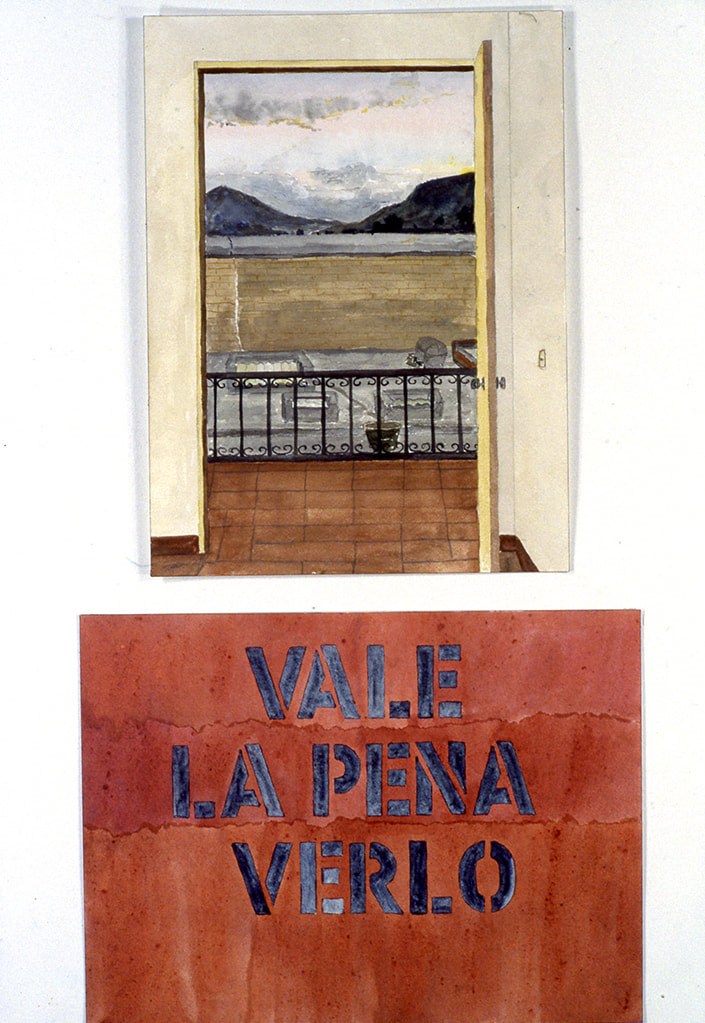

Tariq suggested that while he went to do his interview that I take time out to "throw some paint on paper" - his way of trying to lift the gloomy atmosphere of the hotel and the immediate crisis - he knew that I enjoyed doing watercolours when I travelled. In this watercolour, I painted the view from the balcony of my room looking over the back of the Embassy Hotel. I took his words literally and did a very spontaneous painting. I really like this watercolour dedicated to Tariq, as it has a really defiant and liberating spirit about it - strange as it is actually in contradiction to how I was feeling at that time. It was the only watercolour that I managed to do on the trip.

It was a few days after 9/11 when Tariq and I met up in Beirut. Tariq was based in Cairo at the time working as a journalist and I was in Tirana, Albania attending the first Art Biennial that was in collaboration with the Italian journal Flash Art. The shocking news of the attacks in the USA totally eclipsed this inaugural cultural event on the very margins of the art world, with international artists and curators cancelling their trips to Tirana and those already in the city frantically booking the first possible flights out. All flights to North America had been cancelled.

Tariq and I had decided not to cancel our trip and to carry on with our plans to meet-up. When I managed to get a flight to Beirut there was a feeling of anxiety and foreboding in the city, with the fear that some location in the Muslim world would be attacked in retaliation. When I caught up to Tariq, he was going off to do an interview. While we had travelled together in the Middle East previously when my son was much younger, this was our first time in Lebanon together - the home country of my parents and his grandparents.

Tariq suggested that while he went to do his interview that I take time out to "throw some paint on paper" - his way of trying to lift the gloomy atmosphere of the hotel and the immediate crisis - he knew that I enjoyed doing watercolours when I travelled. In this watercolour, I painted the view from the balcony of my room looking over the back of the Embassy Hotel. I took his words literally and did a very spontaneous painting. I really like this watercolour dedicated to Tariq, as it has a really defiant and liberating spirit about it - strange as it is actually in contradiction to how I was feeling at that time. It was the only watercolour that I managed to do on the trip.

Roo BorsonWest Lake State Guest House, Hangzhou, China

Beneath the window, on a side table placed between two armchairs, sits a small celadon dish, lidded, holding, on a given day, two loquats, or two dried plums, or a squat pyramid of blueberries. Eaten or not, each day the fruits of the season will be replaced with others. Everything else follows from this. The view from the window, the secluded pool draped with willow and maple, the leafy detritus skimmed from the surface before dawn by workers in conical straw hats, and on rainy days by the same hatted workers now wearing black garbage bags with holes cut out for the head and arms. The glossy, perfectly trimmed hectares of gardens, the many walkways and bridges. The bench facing West Lake, with its own photo beside it, of Xi Jinping and Barack Obama seated with glasses of some no doubt exquisitely fragrant tea. A little farther on, the slippery path to the carefully preserved, one-room wooden cabin where Mao Zedong once stayed continues uphill through the gloom of unkempt trees where stinging insects will find the walker and miniature security cameras perched on tall metal poles silently record everything that happens. Is this how history is made? The elusive beauty of the arts, even of the garden arts, seems a small bandage on an open wound, but no one can say for sure how the wound was made, or whether it can be healed. |

Andy Patton

Hotel Annalena, Via Romana, 34, Florence, Italy

I first visited Italy in 1989. Ostensibly I was there to study the early Renaissance frescoes of Giotto and Uccello, and later ones like the Pontormos in Galluzzo which he painted during the plague years. But I had another agenda too: I wanted to visit the sites of Eugenio Montale’s poems. The modernist poet had inhabited my consciousness since I first came across his dense, refractory verse as an undergraduate. I felt at times that his poems were addressed to me across a gulf of years and language and culture. Visiting his poems took me to the Cinque Terra, to Monterosso which was his family’s summer home, where I had a dinner of cuttlefish in his honour and Sciacchetrà, the local wine, whose grapes had come from the hill directly behind the hotel where I was staying. The owner filled me with stories about Montale, some of which might well have been true. Montale’s father, he said, alternated with his father as mayor of the little town. I visited Ravenna to see the glittering early Christian mosaics, and the street where a newspaper fluttered down in a sequence of Antonioni’s Red Desert. As I walked from the station to my hotel, the town seemed deserted. Italy still kept the sosta, the mid-afternoon pause in the heat of the day. After few days of exploring, I took a taxi to Porto Corsini, where Montale’s “Dora Markus” takes place. The wooden pier, or bridge if that’s what it was, had vanished. So too had Mussolini’s despicable racial laws. “Ravenna is far away, a ferocious faith distills its poison,” says the poem. But Ravenna is near, just a few kilometres away; Porto Corsini is one of the city’s beaches. Was this a teaspoon of Montale’s bitter irony? Was Christianity the ferocious faith? Dora was probably a figure standing in for someone else, a lesser Beatrice, one of many in his poems. Probably Dora was a figure for Irma Brandeis, who was Jewish. Her “flowering Carinthia”, the homeland she gestured to, was Austria, which was neither her homeland nor welcoming, now that it had been absorbed by Hitler’s Germany and its own antisemitism was in bloom. Of course I stayed in Florence, absorbing its lessons. I stayed in what was then the Pensione Annalena in the Oltrarno, past the Pitti Palace, almost at the Porta Romana. “We’re together on the veranda of the Annalena defleaing the rhymes of the reverend itchy John Donne.” A banal moment, the sort of thing he treasured, in a quite astonishing, brief, as usual radically understated poem, “Inside/Outside.” Of course he doesn’t mention that there in the Annalena, Jews were hidden from the Nazis. I had made a copy of the poem and carried it with me, intending to give it to the staff--if by any chance they didn’t know that Montale had mentioned the Annalena. They didn’t seem terribly impressed. My room was not much more than a broom closet, but I was treated to the whispers and muffled laughter of two of the staff who seemed to be having an illicit affair. By the time Janice and I stayed there, twenty years later, it had become a somewhat eccentric hotel, with a pamphlet documenting its history, literary and otherwise. It records the fact that more than twenty-five Jewish and partisan families were sheltered there, living under false names. It records too that Carlo Levi, both Jewish and partisan, wrote Christ Stopped at Eboli there, his memoir of life in internal exile in Basilicata. Beautiful, haunting, lucid in its style, it brought "the problem of the south” to national attention. The title of the book is an expression used by the people of Gagliano, which was the village to which he was confined.“We’re not Christian, they say; Christ stopped at Eboli. Christian means, in their language, a man, a human being. And that phrase I heard repeated so many times, in their mouths is perhaps nothing more than the expression of the most dejected sense of inferiority.” So Levi reported. His beautiful, baking indictment found its way to me, becoming indispensable, this record of a discarded people that Levi said began as “painting and poetry, and then theory and the joy of telling the truth.” And finally, I read with pleasure, the hotel pamphlet recalls that Montale spent time there with Irma Brandeis, his Dora Markus. Even better, that “Inside/Outside” speaks of the Annalena. “One of his most passionate lyrics,” it proudly states. I wouldn’t go that far, and anyway, in Montale passion is always compressed and transformed, like everything else, into a strange object that only half reveals itself. |