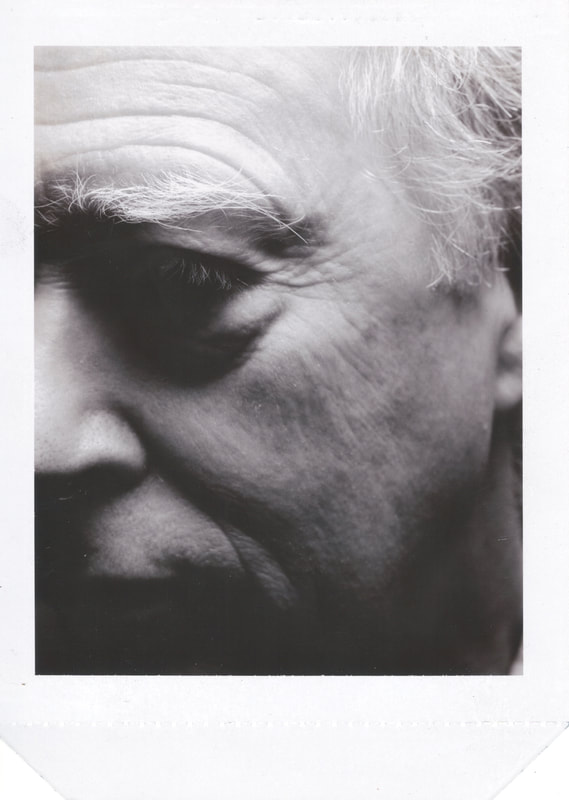

Michael Snow: notes on notes

Much has been written and said about Michael Snow’s presence and his contributions to the languages of art over 65 years, to nominate 1957 as a reasonable start date. His first solo exhibition at the Greenwich (later, Isaacs) Gallery was in late 1956. Five members of the original Group of Seven were still alive. The Toronto-based Painter’s Eleven were in their heyday, and William Ronald who had resigned from Painters Eleven by then was taken on by the prestigious Kootz Gallery in New York in 1957. Ronald was only two years older than Snow.

This is not a rewind and restatement of Snow’s extensive international career, and seemingly diverse practices – the New York Times tribute aptly described him as a polymath – the honours and well-deserved awards and accolades. These are my notes on Michael Snow, who I came to know through my gallery work and in private moments, selecting experiential facets of his work with music, sound and moving image, and performing with the free improvisation group CCMC.

While not adhering to chronology, my first encounters were with his 3D work in 1967, one at Expo’67. If that event captured a spirit of the times – a giddy optimism – the stainless steel walking women that populated the Expo island site gave a corporeal and unearthly presence to that spirit; the clean contour of women always moving forward through Man and His World and reflecting the flow of world visitors … always moving forward.

I could cite Umberto Boccioni’s celebrated 1913 sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space --https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81179 -- as ‘precedent,’ but Michael’s WW brought the figure-vision into that and our time without re-stating, or Alberto Giacometti’s figures in the city sculptures: https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/checklist/lets-talk-art-giacometti-and-the-city

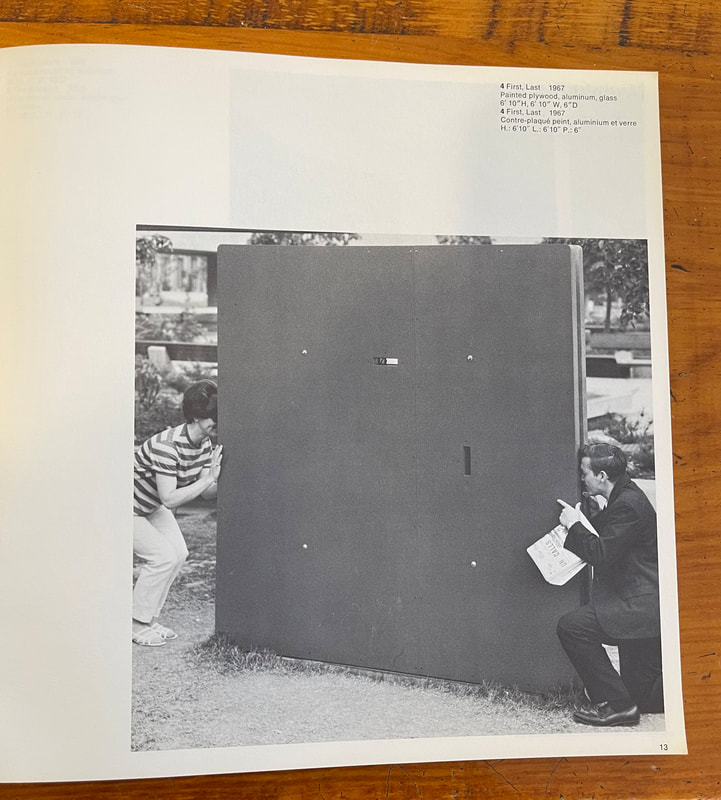

Before or after the Expo visit, I saw Michael’s First, Last (later titled First to Last) at Toronto City Hall in Dorothy Cameron’s Sculpture 67 exhibition for the National Gallery of Canada. I didn’t wonder why this was a different Michael Snow as I was too young to have been instructed or indoctrinated into art taxonomy. First, Last was so unPop at the height of Pop (James Rosenquist’s monumental mural Firepole was hung in space in the American Expo pavilion). Ten years, I began to understand and appreciate that this wasn’t the question to be posed.

This is not a rewind and restatement of Snow’s extensive international career, and seemingly diverse practices – the New York Times tribute aptly described him as a polymath – the honours and well-deserved awards and accolades. These are my notes on Michael Snow, who I came to know through my gallery work and in private moments, selecting experiential facets of his work with music, sound and moving image, and performing with the free improvisation group CCMC.

While not adhering to chronology, my first encounters were with his 3D work in 1967, one at Expo’67. If that event captured a spirit of the times – a giddy optimism – the stainless steel walking women that populated the Expo island site gave a corporeal and unearthly presence to that spirit; the clean contour of women always moving forward through Man and His World and reflecting the flow of world visitors … always moving forward.

I could cite Umberto Boccioni’s celebrated 1913 sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space --https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81179 -- as ‘precedent,’ but Michael’s WW brought the figure-vision into that and our time without re-stating, or Alberto Giacometti’s figures in the city sculptures: https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/checklist/lets-talk-art-giacometti-and-the-city

Before or after the Expo visit, I saw Michael’s First, Last (later titled First to Last) at Toronto City Hall in Dorothy Cameron’s Sculpture 67 exhibition for the National Gallery of Canada. I didn’t wonder why this was a different Michael Snow as I was too young to have been instructed or indoctrinated into art taxonomy. First, Last was so unPop at the height of Pop (James Rosenquist’s monumental mural Firepole was hung in space in the American Expo pavilion). Ten years, I began to understand and appreciate that this wasn’t the question to be posed.

A question posed

2003. While doing collection research in Brisbane for the University of Queensland Art Museum, I had correspondence with Melbourne artist Robert Rooney (1937-2017). He did not have a computer for email, nor phone or fax. We wrote letters and asked if he was aware of Michael Snow’s work because I recognized affinities with Rooney’s painting, photography (also a musician), which did not appear in any critical writing. Rooney responded:

2003. While doing collection research in Brisbane for the University of Queensland Art Museum, I had correspondence with Melbourne artist Robert Rooney (1937-2017). He did not have a computer for email, nor phone or fax. We wrote letters and asked if he was aware of Michael Snow’s work because I recognized affinities with Rooney’s painting, photography (also a musician), which did not appear in any critical writing. Rooney responded:

Michael Snow’s work was known to me. The paintings and drawings I did in 1966 using a stencil of a female figure owe something to Snow’s Walking Woman series. I no longer have a copy of the Nova Scotia book, Cover to Cover, but I remember being interested in his film Wavelength. |

If this seems minor, Rooney was living and working halfway around the world and did not travel. Artists pay attention to what matters to them, what feeds them, as with musicians. But more on that later. It was not the only time that Michael Snow came up in conversations with artists in Australia.

Also from Rooney’s first letter: “Much that has been written about my relation to suburbia says more about the writers than it does about me [but] Paul Taylor [Australian art critic and curator] once described my life as uneventful. I disagree.” No one has ever described Michael Snow’s life as uneventful, but his life’s work-and-moments are events of a different order. I have said often enough that if you really want to understand his thinking and being, listen to him – his music and sound work – and watch the films.

Most often he and I talked about music. Was he a good musician? Yes, but not in the way non-musicians imagine (I would include some if not much of the audience for art). Non-conforming music is tolerated more than embraced. Having lived and worked in music and art for decades, I have some thoughts on why these worlds hardly ever cross, even with popular idioms.

Also from Rooney’s first letter: “Much that has been written about my relation to suburbia says more about the writers than it does about me [but] Paul Taylor [Australian art critic and curator] once described my life as uneventful. I disagree.” No one has ever described Michael Snow’s life as uneventful, but his life’s work-and-moments are events of a different order. I have said often enough that if you really want to understand his thinking and being, listen to him – his music and sound work – and watch the films.

Most often he and I talked about music. Was he a good musician? Yes, but not in the way non-musicians imagine (I would include some if not much of the audience for art). Non-conforming music is tolerated more than embraced. Having lived and worked in music and art for decades, I have some thoughts on why these worlds hardly ever cross, even with popular idioms.

|

Rodney Graham: One of my dreams is to become a rock star-cum-painter, like Ronnie Wood and David Bowie.

Matthew Higgins: But surely the downside of that scenario is that your art would never be taken seriously? Rodney Graham: I know. It’s a hopeless situation. Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2002 Michael Snow: The CCMC has been largely disregarded by the jazz scene in Toronto, perhaps because it doesn’t fit the right category [and] our use of electronics has been described disparagingly as “sound effects." Yes, there are sometimes what could be called “sound effects” – part of the incredible range of sounds available with electronics – but they are musical materials. Interview with Bruce Elder in Music/Sound, The Michael Snow Project, 1994, p240 |

Listening

When asked, I’ve said that the key to being a good musician is the ability to listen to yourself and others. You also need skills – talent – passion – and always be prepared to learn, however it comes. Sometimes you figure it out for yourself, alone.

I know this happened but can’t recall or confirm when. Dinner at artist friend’s house in Toronto; Michael and Peggy Gale were there. The teenage son of the artist, then studying at the Conservatory, was practicing piano in a small room off the dining room. Michael said (quietly), ‘I want to play music with him.’ Michael was listening. It was not the only time the two talked about music.

The Music Gallery was a few blocks away from where I lived in west end Toronto in the late 1980s to late 1990s. Michael and the CCMC played there regularly. One night, I may have been among a small handful in the room—certainly there were as many musicians playing as audience. It didn’t matter to the musicians – they were playing and creating.

When asked, I’ve said that the key to being a good musician is the ability to listen to yourself and others. You also need skills – talent – passion – and always be prepared to learn, however it comes. Sometimes you figure it out for yourself, alone.

I know this happened but can’t recall or confirm when. Dinner at artist friend’s house in Toronto; Michael and Peggy Gale were there. The teenage son of the artist, then studying at the Conservatory, was practicing piano in a small room off the dining room. Michael said (quietly), ‘I want to play music with him.’ Michael was listening. It was not the only time the two talked about music.

The Music Gallery was a few blocks away from where I lived in west end Toronto in the late 1980s to late 1990s. Michael and the CCMC played there regularly. One night, I may have been among a small handful in the room—certainly there were as many musicians playing as audience. It didn’t matter to the musicians – they were playing and creating.

|

Michael Snow: The music of the CCMC is improvised. Maybe a useful distinction can be made between extemporization and improvisation – the form term signifying the creative process which is best exemplified in jazz: a “spontaneous” recollection, drawing from a reservoir of accumulated musical knowledge and instrumental ability. Improvisation could denote a special case, an unrealizable “ideal” where, with regard to form, expression, and technical facility, the musician is as limited by what he knows as what he doesn’t know.

Bruce Elder interview pp137-38 |

Over the years, I have accumulated a modest collection of Michael’s recordings on vinyl, cassette and CD.

Brisbane Australia, 2001. I came across a CD reissue of New York Ear and Eye Control (1964) in an off-beat record store, and emailed Michael about my discovery. He was not aware of this pressing and told me to buy it. Not cheap, but I did, and brought it with me on a trip to Canada. Visiting, I showed it to him. He read the reissue booklet and pointed out errors. I sheepishly asked him to sign it: he did, and Peggy followed up: ‘He’s come all this way, please give him a copy of Three Phases.’ Michael did and signed it.

https://electrocd.com/en/album/1383/Michael_Snow/3_Phases

Early 2019. At a small restaurant gathering of invited art world ‘suspects’ in Toronto. Michael and I talked again about music and New York Ear and Eye Control. The conversation led to Don Cherry and John Tchicai. Both played on the recording for the film. Cherry is famous – and not just for being Neneh Cherry’s stepfather – Tchicai less so. But Michael’s admiration for his playing came like a spark across the table. Did anyone else at the table hear that or if….would they have responded … ‘what?’

December 2001? In a used record store in downtown Vancouver, I came across a copy of The Last LP CD. I had it on the original vinyl but bought it. A post-it note in the booklet by (a strong hunch) a disbeliever: “Read this first!! This CD is a send-up of ethno/anthro field recordings!” Sadly, this previous owner wasn’t listening. Or really reading. The extensive background notes, and introduction, written by Michael, are inspired fabulations. His introduction concludes with impassioned examples, citing recordings by Louis Armstrong’s Hot 7, Glenn Gould and the Romanian classical pianist Dinu Lipatti. The Last LP premise is declared by Michael in the third person, in the booklet credit pages. The type reversed, to be read in a mirror: “This was Snow’s first attempt at ‘speaking in tongues’.”

Early 2019. At a small restaurant gathering of invited art world ‘suspects’ in Toronto. Michael and I talked again about music and New York Ear and Eye Control. The conversation led to Don Cherry and John Tchicai. Both played on the recording for the film. Cherry is famous – and not just for being Neneh Cherry’s stepfather – Tchicai less so. But Michael’s admiration for his playing came like a spark across the table. Did anyone else at the table hear that or if….would they have responded … ‘what?’

December 2001? In a used record store in downtown Vancouver, I came across a copy of The Last LP CD. I had it on the original vinyl but bought it. A post-it note in the booklet by (a strong hunch) a disbeliever: “Read this first!! This CD is a send-up of ethno/anthro field recordings!” Sadly, this previous owner wasn’t listening. Or really reading. The extensive background notes, and introduction, written by Michael, are inspired fabulations. His introduction concludes with impassioned examples, citing recordings by Louis Armstrong’s Hot 7, Glenn Gould and the Romanian classical pianist Dinu Lipatti. The Last LP premise is declared by Michael in the third person, in the booklet credit pages. The type reversed, to be read in a mirror: “This was Snow’s first attempt at ‘speaking in tongues’.”

|

Michael Snow: A friend of mine was with a visitor one afternoon. While they chatted over coffee, she had The Last LP on. The visitor said she really liked the music and where could she buy it. A week later the visitor phoned and angrily said to her, “Why didn’t you tell me?!!!” I would have asked “But do you still like the music?”

Bruce Elder interview, p220 |

Mid-2006. I was in Canada again and invited to dinner at Michael and Peggy’s house. We ate in the kitchen because the modest dining room was seriously occupied by a vintage grand piano (it may have been his mother’s piano). The huddle in the kitchen was social and cheery; the food was good and comforting. The piano in the other room was there to be played. Every day. I think so.

Duration

Stating the obvious, time and duration is inescapable in the structural tissue of music and moving image.

Love Me Do, 1962, the Beatles first single, is 2:22.

John Cage’s 4’ 33 is four minutes and thirty-three seconds.

Performing Erik Satie’s Vexations (notated in 1893-94) – one sheet of music to be repeated 840 times – takes 18+ hours. It was first performed by John Cage and a team of pianists in 1963, which included John Cale, later of The Velvet Underground: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mqO-xsRyTM

Michael was living in New York at that time. (Did he attend the John Cage-Vexations performance?)

For 2&3D art the visitor-viewer determines the length of engagement. The oft-spoken phrase ‘how long did it take you to make this’ is never a question for music. From Archie Shepp’s liner notes for the 1965 album New Thing at Newport, John Coltrane/Archie Shepp:

Duration

Stating the obvious, time and duration is inescapable in the structural tissue of music and moving image.

Love Me Do, 1962, the Beatles first single, is 2:22.

John Cage’s 4’ 33 is four minutes and thirty-three seconds.

Performing Erik Satie’s Vexations (notated in 1893-94) – one sheet of music to be repeated 840 times – takes 18+ hours. It was first performed by John Cage and a team of pianists in 1963, which included John Cale, later of The Velvet Underground: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mqO-xsRyTM

Michael was living in New York at that time. (Did he attend the John Cage-Vexations performance?)

For 2&3D art the visitor-viewer determines the length of engagement. The oft-spoken phrase ‘how long did it take you to make this’ is never a question for music. From Archie Shepp’s liner notes for the 1965 album New Thing at Newport, John Coltrane/Archie Shepp:

The imperatives of [Coltrane's] conception often made it necessary for him to improvise at great length. I don't mean he proved that a thirty or forty-minute solo is necessarily better than a three-minute one. He did prove, however, that it was possible to create thirty or forty minutes of music, and in the process, he also showed the rest of us we had to have the stamina – in terms of imagination and physical preparedness – to sustain these long flights. |

Michael attended Coltrane Quartet concerts while living in New York in the early 1960s.

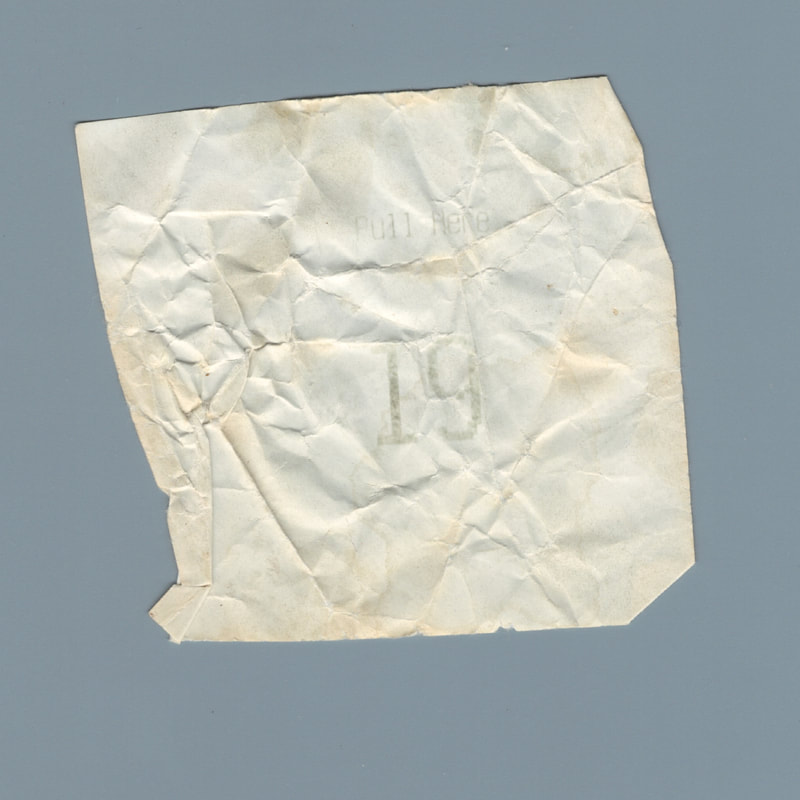

Early 2020. The Art Museum, University of Toronto exhibition Listening to Snow. I experienced Michael’s sound work Waiting Room, 2000, and a title he used for a 1979 photograph and mixed media work. Scroll down: https://www.embassyculturalhouse.ca/works.html From exhibition curator Liora Belford’s text, beginning with a Merleau-Ponty assertion about listening to the bodily experience of the space:

Early 2020. The Art Museum, University of Toronto exhibition Listening to Snow. I experienced Michael’s sound work Waiting Room, 2000, and a title he used for a 1979 photograph and mixed media work. Scroll down: https://www.embassyculturalhouse.ca/works.html From exhibition curator Liora Belford’s text, beginning with a Merleau-Ponty assertion about listening to the bodily experience of the space:

Time, in this sense is understood not as an external consciousness, but rather as an experience. In Waiting Room (2000) Snow manipulates this experience by controlling the duration of his audience’s attentiveness: each is instructed to take a number, then wait for the number to come up on a sign, at which point they are to leave. |

My number was “19.”

The sound on the loudspeakers was a real-time, ambient fed from live microphones installed in the Reading Room at Hart House. A computer program determined the duration of each listening, but variable. It could be 30 seconds or four minutes. After, I was directed to the Reading Room where the microphones were installed. I sat and took photographs of a radiator with a sign above:

CAUTION. Radiators Are On For the Season (Very Hot)

Summer 2008. I invited Michael to present Solar Breath (Northern Caryatids) 2002 as a single gallery installation at the Confederation Centre Art Gallery, Charlottetown. Our offices were on the other side of the projection wall. The sound came through as a fascinating and disembodied audio experience … the flapping of the curtain, pans clattering, Peggy’s voice. In the gallery, a spatial and acoustic experience. The projection was the scale of the domestic window, as instructed by Michael, but the gallery space was/is institutional utopic-modern (built in 1964), approx. 14x14 metres and the wall, 4 metres high.

Hence, two versions of space that could be experienced if you were paying attention. Michael agreed to this staging.

An excerpt: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mrl-66m9lO4

There is no particular beginning or end to Solar Breath, which brings to mind an Umberto Eco commentary:

Hence, two versions of space that could be experienced if you were paying attention. Michael agreed to this staging.

An excerpt: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mrl-66m9lO4

There is no particular beginning or end to Solar Breath, which brings to mind an Umberto Eco commentary:

|

Italy is one of those countries in which one is allowed to enter a cinema at any time… and then stay to see it again from the beginning. I think this is a good custom, because I hold that a film is much like life in a certain respect: I entered into this life with my parents already born and Homer’s Odyssey already written, and then I tried to work out the story going backward.

Six Walks in the Fictional Woods, 1994, p65. |

Two Notes on Silence

Condensation (A Cove Story) 2009 is a silent colour video shot in coastal Newfoundland.

Condensation (A Cove Story) 2009 is a silent colour video shot in coastal Newfoundland.

|

Michael Snow: This work is a temporally compressed, condensed recording of several weather-events which took place on and near a wild landscape in the Canadian Maritimes.

|

http://angelsbarcelona.com/en/artists/michael-snow/projects/condensation-a-cove-story/232

I included this video in my selection for a 2019 outdoor project My World is Empty … Without You at the Confederation Centre, projected on the exterior wall of the Centre’s Theatre pavilion. I decided that all the videos had to be silent and let the sound be of-the-world. One video was projected continuously each night. The Theatre wall faced a street with restaurants and outdoor seating. A “captive” audience in a social scenario – ever-changing over the course of the evening. An Atlantic region source work in the Atlantic region was also a consideration—as if to collapse geographic space. The accidental viewer or tourist didn’t need to know that.

So is This, a 1982 silent film, with only one word ever on screen. An excerpt: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8i6H1KDJ9Ic

It is habit of mind to read and speak (even to oneself) ‘printed’ words. In that way, not so silent. The varying pacing of the words appearing on screen gives the watching-experience a bodily presence. I was recruited as the projectionist for the screening at the opening exhibition of The Power Plant in 1987.

Performing

9 February 2020. Just before the pandemic. I went to hear Michael play with CCMC members John Oswald, John Kamevaar and Paul Dutton, a Sunday afternoon during the opening of the Early Snow exhibition at the Art Gallery of Hamilton. The performance space was crowded, but people dropped off, having done their ‘duty’? After the 30 or so minute performance, I said to Michael that I was inspired to get a piano. He quietly responded, “It’s not the instrument, it’s the player.”

Of course.

Returning to the question, was Michael a good player? Watch Toronto Jazz 1963: NFB directed by Donald Owen. Scroll around to around 15:30. Michael playing piano with the Alf Jones Quartet at the after-hours House of Hambourg and then talking with Don Francks in his studio:

https://www.nfb.ca/film/toronto_jazz/

Composing with a different instrument. 2 Radio Solos, 1980 (short-wavelength pieces played on 1962 radio) originally released on cassette in 1988. Don’t try to listen. Let it play. Do something else. Wash the dishes … do house cleaning. Let the sound be the sound.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jq4SVJA8I0Q

Attention to detail. Like listening.

I’m not arguing for Michael’s music, sound and filmwork above all else, but it would be negligent not to cite a physical work. My nominated choice (audacity?) is Redifice, 1986, first shown at Expo 86 in Vancouver. I was instrumental in bringing it into the Art Gallery of Hamilton collection in 1995 (it was not the easiest work to pitch to the Committee). The ‘gift’ was consummated at dinner, the home of the donor; Michael sitting at the end of the table, but not at ‘the head of the table.’ I was sitting on his corner. (Whatever we talked about, Michael was unperturbed and gracious.) A loan request for Redifice came from Chris Youngs, the director/curator of the Freedman Gallery, Albright College in Reading PA for the group exhibition Timeframes in early 1997. I went to oversee the installation: Michael was there too. The gallery space was not ideal for such a large free-standing work, over 6 metres long and 2.44 metres high, plus the limitations of the fixed lighting system, especially for the hologram elements. Redifice is not typical of Michael’s work, but nothing is ”so typical.” Experiencing Redifice requires patience, duration and a suspension of belief (what you believe, rather than disbelief). It can only be approached as a processional viewing, but you can start or enter anywhere – at the ends, the middle, or the other side, stopping to examine elements and details, unified by the red wall-carcass, but not as if a boundary.

https://www.artgalleryofhamilton.com/agh-abroad-redifice-in-la/

Scroll down for installed image of Redifice in Los Angeles: https://manpodcast.com/portfolio/no-351-3d-double-vision-bridget-alsdorf/

Michael was hands on with adjustments that only he could determine. There was no art glory in a work being shown in a small college art gallery, but it mattered to Michael.

And it mattered to Chris Youngs: “One of my central objectives is to promote Canadian art internationally” (statement, 1986). Youngs arrived in Toronto in 1967 (yes, that year). One of his first initiatives was to establish a warehouse gallery, that later morphed into the artist run centre A Space.

Michael and I stayed at the same hotel, near the intersection of Interstate highways 422 and 222. We had dinner in the hotel one night. I don’t recall what we talked about, but I’m sure the bleak winter and isolating hotel location did come up.

Above all, Michael’s generosity was always present– to younger artists, musicians, and people like me. I felt comfortable. There was always something to talk about.

Postscript

From the CBC tribute headline: “artist who ‘knew no boundaries’”.

From Global News, [the artist] “who ‘demolished boundaries’ of art.”

I don’t think Michael ever thought of boundaries but rather in terms of his engagement:

I included this video in my selection for a 2019 outdoor project My World is Empty … Without You at the Confederation Centre, projected on the exterior wall of the Centre’s Theatre pavilion. I decided that all the videos had to be silent and let the sound be of-the-world. One video was projected continuously each night. The Theatre wall faced a street with restaurants and outdoor seating. A “captive” audience in a social scenario – ever-changing over the course of the evening. An Atlantic region source work in the Atlantic region was also a consideration—as if to collapse geographic space. The accidental viewer or tourist didn’t need to know that.

So is This, a 1982 silent film, with only one word ever on screen. An excerpt: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8i6H1KDJ9Ic

It is habit of mind to read and speak (even to oneself) ‘printed’ words. In that way, not so silent. The varying pacing of the words appearing on screen gives the watching-experience a bodily presence. I was recruited as the projectionist for the screening at the opening exhibition of The Power Plant in 1987.

Performing

9 February 2020. Just before the pandemic. I went to hear Michael play with CCMC members John Oswald, John Kamevaar and Paul Dutton, a Sunday afternoon during the opening of the Early Snow exhibition at the Art Gallery of Hamilton. The performance space was crowded, but people dropped off, having done their ‘duty’? After the 30 or so minute performance, I said to Michael that I was inspired to get a piano. He quietly responded, “It’s not the instrument, it’s the player.”

Of course.

Returning to the question, was Michael a good player? Watch Toronto Jazz 1963: NFB directed by Donald Owen. Scroll around to around 15:30. Michael playing piano with the Alf Jones Quartet at the after-hours House of Hambourg and then talking with Don Francks in his studio:

https://www.nfb.ca/film/toronto_jazz/

Composing with a different instrument. 2 Radio Solos, 1980 (short-wavelength pieces played on 1962 radio) originally released on cassette in 1988. Don’t try to listen. Let it play. Do something else. Wash the dishes … do house cleaning. Let the sound be the sound.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jq4SVJA8I0Q

Attention to detail. Like listening.

I’m not arguing for Michael’s music, sound and filmwork above all else, but it would be negligent not to cite a physical work. My nominated choice (audacity?) is Redifice, 1986, first shown at Expo 86 in Vancouver. I was instrumental in bringing it into the Art Gallery of Hamilton collection in 1995 (it was not the easiest work to pitch to the Committee). The ‘gift’ was consummated at dinner, the home of the donor; Michael sitting at the end of the table, but not at ‘the head of the table.’ I was sitting on his corner. (Whatever we talked about, Michael was unperturbed and gracious.) A loan request for Redifice came from Chris Youngs, the director/curator of the Freedman Gallery, Albright College in Reading PA for the group exhibition Timeframes in early 1997. I went to oversee the installation: Michael was there too. The gallery space was not ideal for such a large free-standing work, over 6 metres long and 2.44 metres high, plus the limitations of the fixed lighting system, especially for the hologram elements. Redifice is not typical of Michael’s work, but nothing is ”so typical.” Experiencing Redifice requires patience, duration and a suspension of belief (what you believe, rather than disbelief). It can only be approached as a processional viewing, but you can start or enter anywhere – at the ends, the middle, or the other side, stopping to examine elements and details, unified by the red wall-carcass, but not as if a boundary.

https://www.artgalleryofhamilton.com/agh-abroad-redifice-in-la/

Scroll down for installed image of Redifice in Los Angeles: https://manpodcast.com/portfolio/no-351-3d-double-vision-bridget-alsdorf/

Michael was hands on with adjustments that only he could determine. There was no art glory in a work being shown in a small college art gallery, but it mattered to Michael.

And it mattered to Chris Youngs: “One of my central objectives is to promote Canadian art internationally” (statement, 1986). Youngs arrived in Toronto in 1967 (yes, that year). One of his first initiatives was to establish a warehouse gallery, that later morphed into the artist run centre A Space.

Michael and I stayed at the same hotel, near the intersection of Interstate highways 422 and 222. We had dinner in the hotel one night. I don’t recall what we talked about, but I’m sure the bleak winter and isolating hotel location did come up.

Above all, Michael’s generosity was always present– to younger artists, musicians, and people like me. I felt comfortable. There was always something to talk about.

Postscript

From the CBC tribute headline: “artist who ‘knew no boundaries’”.

From Global News, [the artist] “who ‘demolished boundaries’ of art.”

I don’t think Michael ever thought of boundaries but rather in terms of his engagement:

|

I make up the rules of a game, then I attempt to play it [and] if I seem to be losing, I change the rules. Beyond the rules lies radical art.

Interview, Globe and Mail, 1 December 1984 |

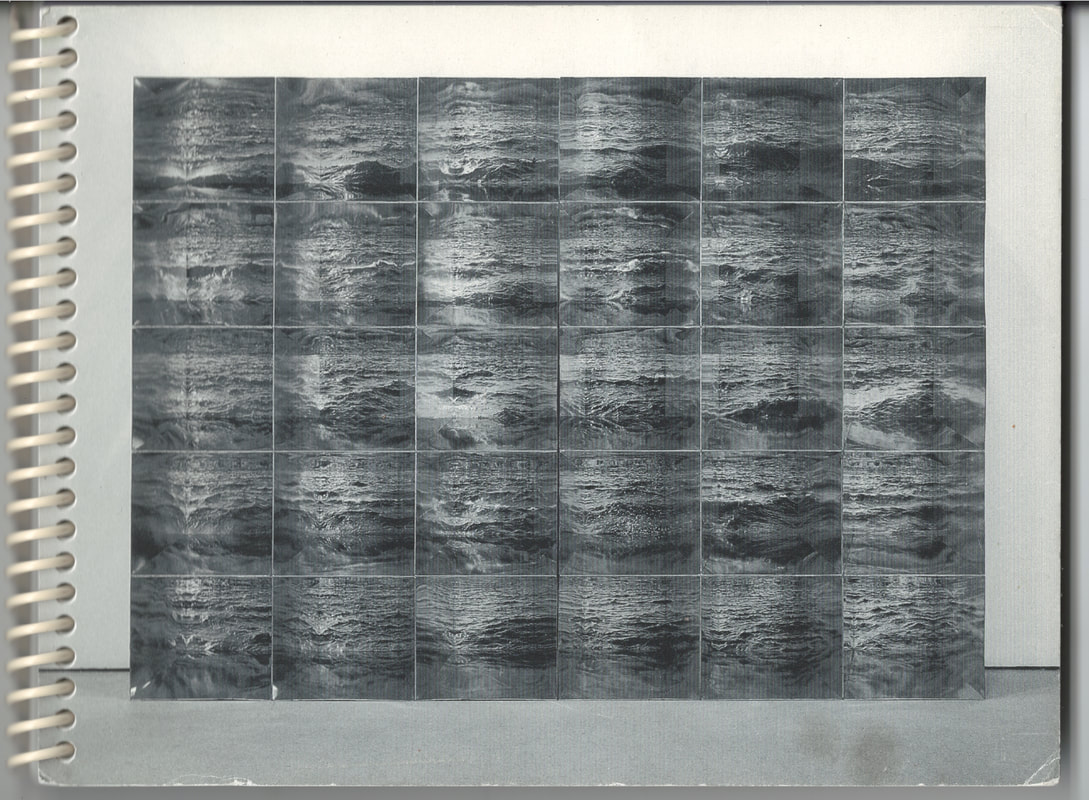

Michael Snow, Atlantic 1967, cover of a 1994-produced Art Gallery of Ontario blank sketchbook

Signed, 18 July 2012. (One blank page less)

Signed, 18 July 2012. (One blank page less)

Thanks to Liora Belford, Margaret Dryden, Al Mattes, and Mani Mazinani for their responses and clarifications.