Roo Borson

|

Roo Borson is a poet and occasional essayist. Her books include the collaborative works Introduction to the Introduction to Wang Wei by Pain Not Bread (Roo Borson, Kim Maltman, and Andy Patton) published by Brick Books, and Box Kite: Prose Poems by Baziju (Roo Borson and Kim Maltman) published by House of Anansi Press. Her most recent solo work is a triptych of poetry books linked through imagery and formal variation: Short Journey Upriver Toward Oishida, followed by Rain; road; an open boat, followed by Cardinal in the Eastern White Cedar, published by McClelland & Stewart/Penguin Random House. She has served as Writer in Residence at Western University, Concordia University, Massey College at the University of Toronto, Green College at the University of British Columbia, and at the University of Guelph. Short Journey Upriver Toward Oishida was awarded the Griffin Poetry Prize, the Governor General’s Award, and the Pat Lowther Award. Born in Berkeley, California, she lives in Toronto with poet and theoretical physicist Kim Maltman. Their combined literary archives are held, alongside the archives of Pain Not Bread, at Library and Archives Canada.

Banner: Cover of Cardinal in the Eastern White Cedar, published 2017 |

|

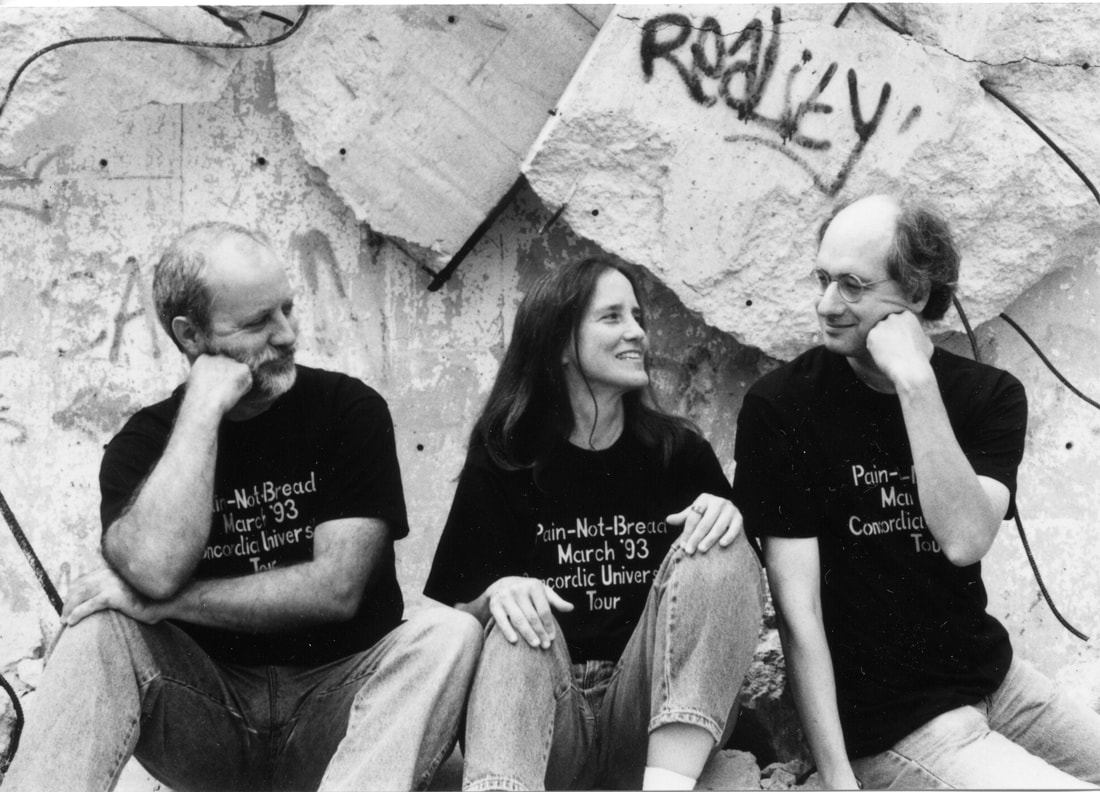

Pain Not Bread was taken by Kim Maltman (on a timer) at the Georgetown site, where Andy Patton did his wallpaper installation (A Doll's House Exposed to the Elements) in an abandoned factory. Photo from circa late-1990s.

|

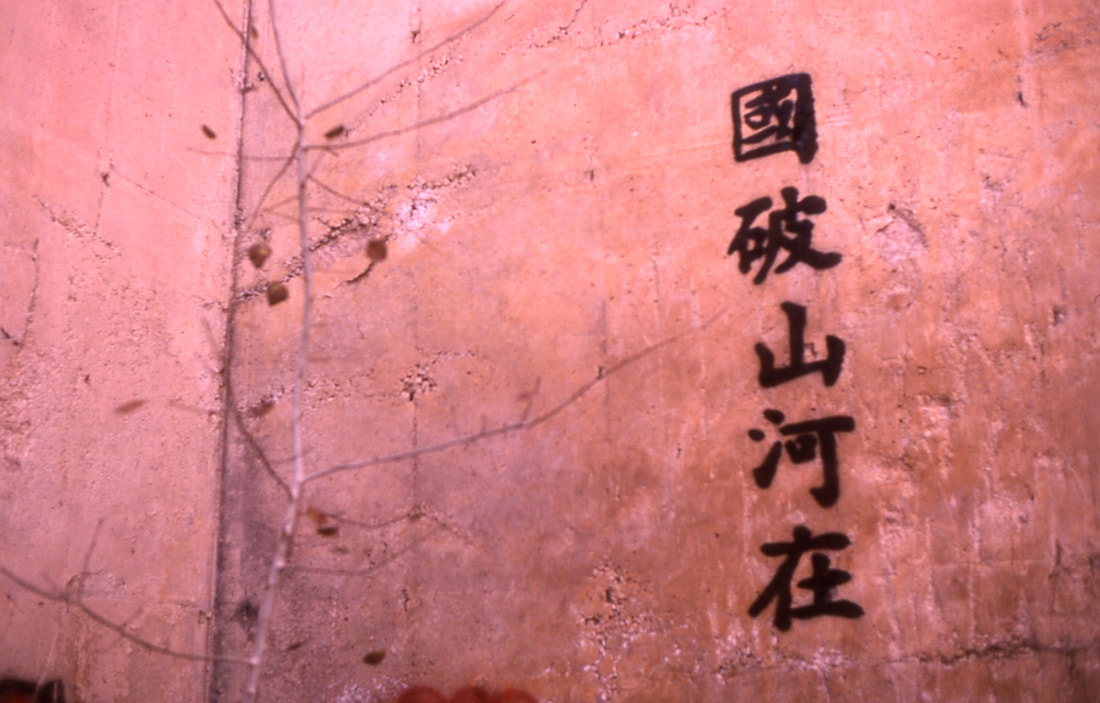

Spray-painted characters on a wall with a cardboard stencil by Kim Maltman. The characters are the first line of Du Fu's poem Spring View, from which we wrote Mountains and Rivers, one of the poems in the Introduction to Wang Wei. (The stencil is now in the Pain Not Bread archive at Library and Archives Canada.)

|

Cardinal in a Cedar Tree, taken by Kim Maltman in Toronto, Winter 2016.

During the Pandemic: Three Pieces, A Memory of Janice Gurney’s Work

By Roo Borson

In Pandemic Time

I wake in black and white. It’s 3:15 a.m. The numerals are printed on the murky space where the television sits hidden in the dark. It is a beautiful composition: patches of charcoal, pale filaments here and there on the walls, and the numerals float, glowing red. The room is saturated with remembered colour.

There are various humming noises too, distant starts and stops, as of trains shunting into and out of stations. There is no way to know whether these are the grunts of the city in its sleep or artifacts of hearing. At times an even tone winks on and off like a foghorn, as if to mark some intimate, indeterminate duration.

Even now, even in these strange times, there are neighbourhoods and neighbours. The lecher who used to wait on the corner and say, every day, with his bloated face as I passed by, “Where you off to? Work?” has passed away, and another neighbour has taken his house. He was only a retired alcoholic. His misery and curiosity were based on the fact that he had nowhere to go and nothing to do. I would nod to him, because that is all that seemed communicable. With this ritual we reached a truce. He was small, square, solid. The grape arbor that used to thrive above his parked car is no longer there. The leer on his face may have been only the indecency of loneliness.

Few of us here have occasion to speak. Our schedules miss each other by minutes. We start our cars or walk to the subway at different times of day, we come and go and are rarely seen. It’s an ordinary part of the city, ugly, once lower but now middle class, not because of any improvement but because of deteriorating means everywhere. Some of the houses are tiny, two or three rooms at most. Shacks, I’m tempted to call them, except they’re solid brick, built by hand after the war by those who constructed homes for themselves in this part of the city.

What seems certain in these times is that whatever can’t be accomplished in a single day must be abandoned. Belief runs out quickly. You may wake with high hopes, but everything unravels with the passing hours. No plan outlives a single period of wakefulness. Questions can be asked — but none less fruitless than my ex-neighbour’s question. None to which we can respond with an answer that amounts to more than a nod or a shake of the head. A little snow might have drifted down absentmindedly before dawn, the first of the season, and vanished before hitting the ground. In the park, someone will have tossed crumbs to the pigeons. Such premeditated generosity is the only hope.

I wake in black and white. It’s 3:15 a.m. The numerals are printed on the murky space where the television sits hidden in the dark. It is a beautiful composition: patches of charcoal, pale filaments here and there on the walls, and the numerals float, glowing red. The room is saturated with remembered colour.

There are various humming noises too, distant starts and stops, as of trains shunting into and out of stations. There is no way to know whether these are the grunts of the city in its sleep or artifacts of hearing. At times an even tone winks on and off like a foghorn, as if to mark some intimate, indeterminate duration.

Even now, even in these strange times, there are neighbourhoods and neighbours. The lecher who used to wait on the corner and say, every day, with his bloated face as I passed by, “Where you off to? Work?” has passed away, and another neighbour has taken his house. He was only a retired alcoholic. His misery and curiosity were based on the fact that he had nowhere to go and nothing to do. I would nod to him, because that is all that seemed communicable. With this ritual we reached a truce. He was small, square, solid. The grape arbor that used to thrive above his parked car is no longer there. The leer on his face may have been only the indecency of loneliness.

Few of us here have occasion to speak. Our schedules miss each other by minutes. We start our cars or walk to the subway at different times of day, we come and go and are rarely seen. It’s an ordinary part of the city, ugly, once lower but now middle class, not because of any improvement but because of deteriorating means everywhere. Some of the houses are tiny, two or three rooms at most. Shacks, I’m tempted to call them, except they’re solid brick, built by hand after the war by those who constructed homes for themselves in this part of the city.

What seems certain in these times is that whatever can’t be accomplished in a single day must be abandoned. Belief runs out quickly. You may wake with high hopes, but everything unravels with the passing hours. No plan outlives a single period of wakefulness. Questions can be asked — but none less fruitless than my ex-neighbour’s question. None to which we can respond with an answer that amounts to more than a nod or a shake of the head. A little snow might have drifted down absentmindedly before dawn, the first of the season, and vanished before hitting the ground. In the park, someone will have tossed crumbs to the pigeons. Such premeditated generosity is the only hope.

Brief Window, Remembered

Or: You wake in a farmhouse. It’s snowing. The digital clock beside you declares, in cherry red numerals, what moment this is.

Or: You wake in a farmhouse. It’s snowing. The digital clock beside you declares, in cherry red numerals, what moment this is.

Brief Window (detail), 1991

Actually, there are two clocks beside you, one on either side. They register different moments, one odd-numbered, one even. One of the clocks is upside down. There are also two photos of the farmhouse in which you are waking: one image is reversed left-to-right, which is not how it feels. The images are blown up precisely to the point where the vacuum becomes visible — viable — between particles. The flakes of snow are the size of lentils. The interstitial medium is not quite nothing, but is infinitely slow, between events which are always latent. Everything is as it would be in a novel, a lyric documentary. The picture is snowing: the snow by turns falling lightly, glancingly, of its own weight. It’s absolutely silent except for the sound of flakes not quite hitting the ground. Their sound muffles the sounds in the living world just as real snow would.

When I wake, surprised to be alive, am I in my own room or inside Janice Gurney’s work? It’s impossible to tell from the clock alone: the time appears random, or at least not predictable beforehand. The work as a whole was structured by the artist — but she left the times the clock would register up to the photographer she commissioned to take the pictures. When the photo shop blew up the images of the farmhouse, accidentally reversing one of them, Gurney decided not only to keep them both, but to turn the image of one of the clocks upside down. The photographer provided the serendipity of both odd and even times: not random, but not predictable beforehand.

These are the details as I remember them. But are they from a slide talk she gave several decades ago, or from a long, strangely unsettling dream?

When I wake, surprised to be alive, am I in my own room or inside Janice Gurney’s work? It’s impossible to tell from the clock alone: the time appears random, or at least not predictable beforehand. The work as a whole was structured by the artist — but she left the times the clock would register up to the photographer she commissioned to take the pictures. When the photo shop blew up the images of the farmhouse, accidentally reversing one of them, Gurney decided not only to keep them both, but to turn the image of one of the clocks upside down. The photographer provided the serendipity of both odd and even times: not random, but not predictable beforehand.

These are the details as I remember them. But are they from a slide talk she gave several decades ago, or from a long, strangely unsettling dream?

Serendipity

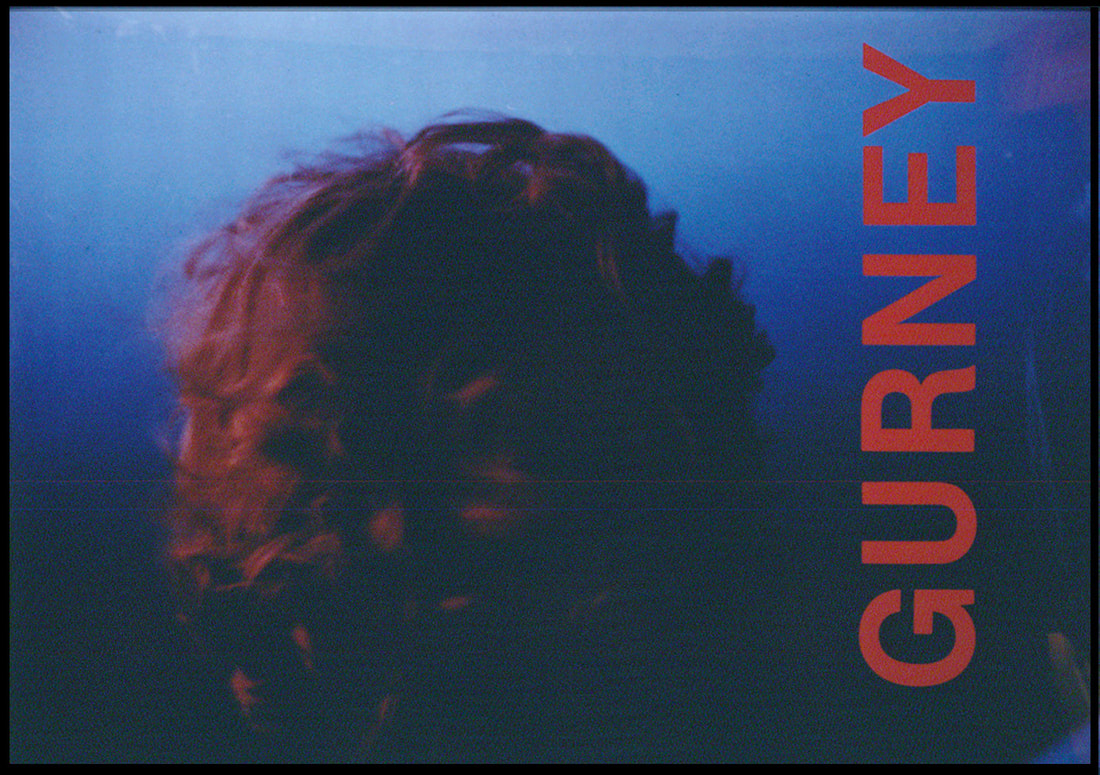

Waking up in the night, and Gurney’s work: they’re unexpected in similar ways. Except that when you wake in an actual room, the disorientation, if it happens at all, is obvious and immediate: either you know where you are and the passing instants confirm this, or else you’ve been travelling and have woken in the wrong room. Much of her work is like this: it’s not quite obvious or immediate, but it dawns on you as the seconds pass that something is wrong. A self-portrait might be of the back of her head: the red-gold filaments of hair at the same time some weird extrusion and as recognizable as a face. The clock is upside down, the farmhouse reversed, and both contribute to the feeling of having been jolted awake in some other place. There’s a doubled-ness to her work, like the doubled-ness of life and art.

Awake now, looking at an image of Brief Window, I find not everything is quite as I’ve remembered it. Did I dream all this? Or has the work been transformed by memory, by a kind of involuntary collaboration? The details I remember are wrong, but the feeling is right. You could say her work has impinged on me, or that I’ve entered it, but without ever fully re-emerging.

Waking up in the night, and Gurney’s work: they’re unexpected in similar ways. Except that when you wake in an actual room, the disorientation, if it happens at all, is obvious and immediate: either you know where you are and the passing instants confirm this, or else you’ve been travelling and have woken in the wrong room. Much of her work is like this: it’s not quite obvious or immediate, but it dawns on you as the seconds pass that something is wrong. A self-portrait might be of the back of her head: the red-gold filaments of hair at the same time some weird extrusion and as recognizable as a face. The clock is upside down, the farmhouse reversed, and both contribute to the feeling of having been jolted awake in some other place. There’s a doubled-ness to her work, like the doubled-ness of life and art.

Awake now, looking at an image of Brief Window, I find not everything is quite as I’ve remembered it. Did I dream all this? Or has the work been transformed by memory, by a kind of involuntary collaboration? The details I remember are wrong, but the feeling is right. You could say her work has impinged on me, or that I’ve entered it, but without ever fully re-emerging.

Name (detail), 1989