Name the Children

The recent discovery of the graves at the Kamloops school is another step towards the healing of people, who still face the outcome of the school system's inhuman treatment of Indigenous children. - Jeff Thomas

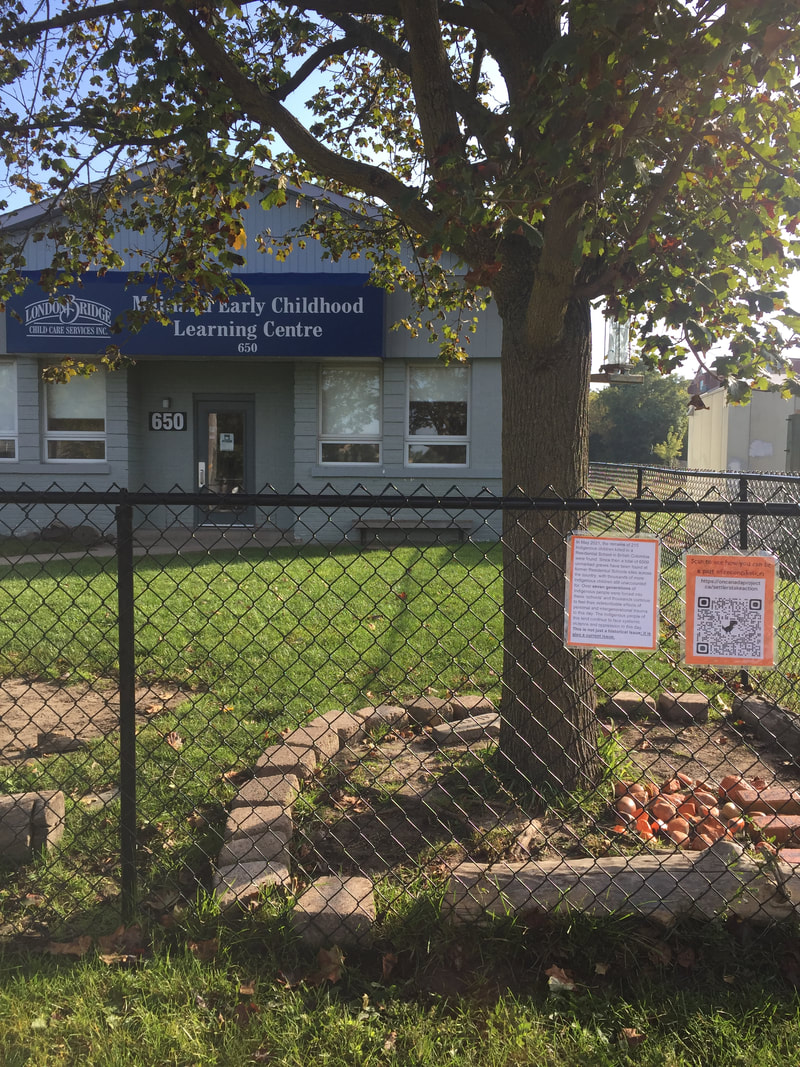

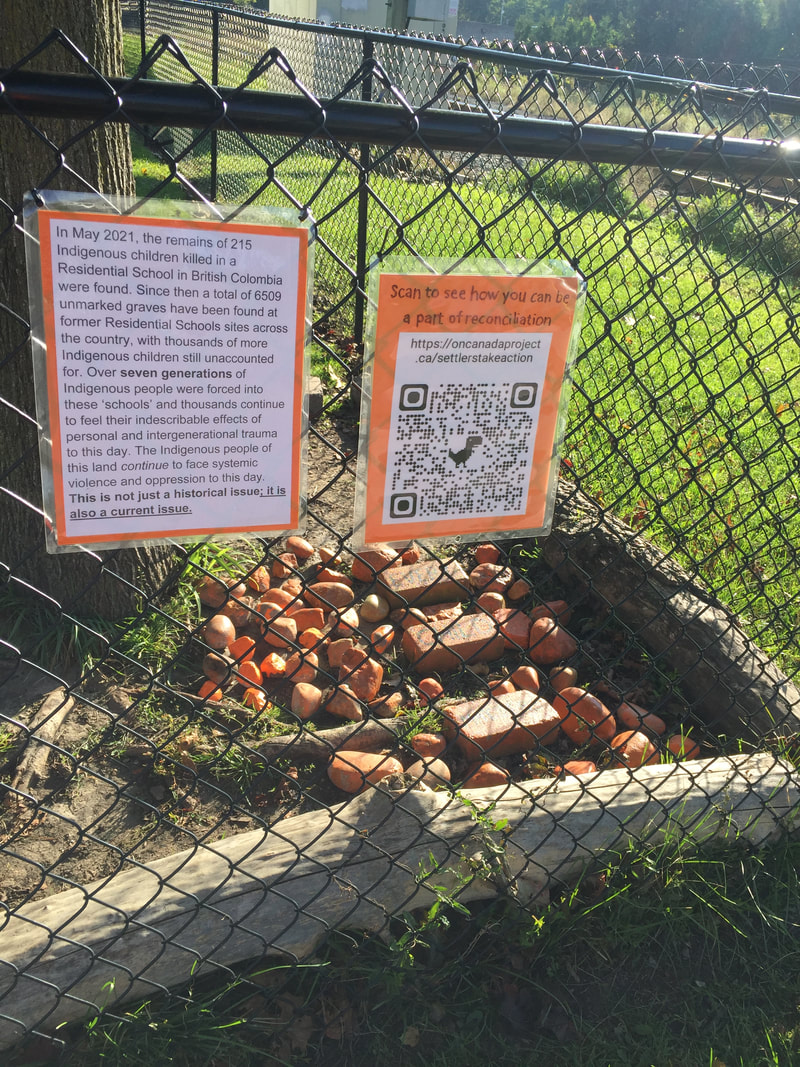

Inaugural National Day of Truth and Reconciliation in London, Ontario on September 30, 2021

Our neighbourhood daycare centre on the inaugural National Day of Truth and Reconciliation

Photo Credit: Jamelie Hassan

London to recognize National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, closing all city buildings

Photo Credit: Jamelie Hassan

London to recognize National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, closing all city buildings

|

London Muslim Mosque's Statements of Solidarity with Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc and the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island (Download bel0w)

|

There are many commemorative events happening across Canada as the horrible and tragic news regarding the deaths of the children at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School comes to light. The poignant assembly of pairs of children's shoes, lined up on the stairs of public buildings and churches, has brought this painful reality home - a tragedy that many Indigenous families were aware of and spoke about over the years...

The Embassy Cultural House is creating this dedicated page that comments on and commemorates the loss of the 215 children whose remains were found at the former site. The Globe and Mail has reported that “The Tk’emlups te Secwepemc First Nation began working to locate the remains at the former Kamloops residential school site in B.C.’s southern interior 20 years ago.” ( May 31, 2021). We extend our condolences and give our support to the families who have suffered the loss of their children and to the survivors and their families who suffered at the hands of this atrocious and brutal system. ECH stands in solidarity with all Indigenous peoples who have suffered untold misery because of colonialism. We hope that this painful history and the ongoing impact of systemic and individual racism that Indigenous peoples continue to experience today will be truly addressed here on Turtle Island. Indigenous cultural workers and story-tellers have addressed these issues and their cultural expressions in all media has given us strength to continue to work towards truth and justice. As a community, we acknowledge that we still have much to learn. In 2002, Jeff Thomas curated from documents and archival photographs in the National Archives of Canada, the powerful touring exhibition Where are the Children: Healing the Legacy of Residential Schools. As Jeff wrote yesterday in response to ECH’s message of condolence :" It was a very stressful exhibition to curate, looking at thousands of children in residential schools across Canada and wondering how many children died at the schools. At the time of the project, school deaths were known about as well, and secret graveyards, but there was no proof. I added a section to the exhibition, at the request of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation - Remembering the Children Who Never Returned Home. I had several images of very young children who had died at several schools in the early 20th century. The recent discovery of the graves at the Kamloops school is another step towards the healing of people, who still face the outcome of the school system's inhuman treatment of Indigenous children." Residential schools were government-sponsored schools run by churches and operated in Canada from 1831 until 1996. The first Residential School was the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Ontario and the last federally-funded Residential School was the Gordon Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan which closed in 1996. Jamelie Hassan, May 31, 2021 | ||||||||||||

If you or anyone you know is Indigenous and needs support, the Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line is available 24/7 at 1-866-925-4419.

RESPONSES FROM THE ECH COMMUNITY:

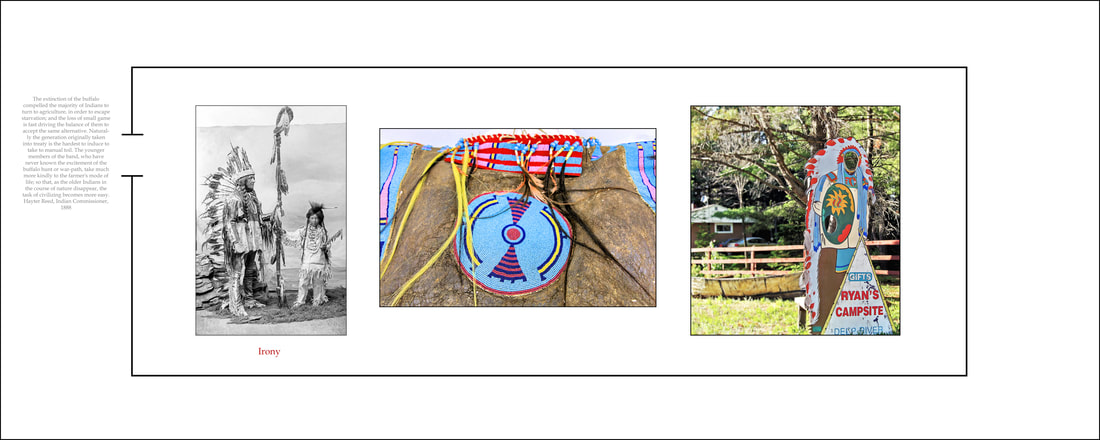

JEFF THOMAS

Text Panel: The extinction of the buffalo compelled the majority of Indians to turn to agriculture, in order to escape starvation; and the loss of small game is fast driving the balance of them to accept the same alternative. Naturally the generation originally taken into treaty is the hardest to induce to take to manual toil. The younger members of the band, who have never known the excitement of the buffalo hunt or war-path, take much more kindly to the farmer's mode of life; so that, as the older Indians in the course of nature disappear, the task of civilizing becomes more easy. Hayter Reed, Indian Commissioner, 1888.

In 2002, my curatorial project "Where are the Children: Healing the Legacy of Residential Schools“ opened on National Aboriginal Day at Library Archives Canada. One of the images I used was a portrait of Hayter Reed, who was the Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs during the last decade of the 19th century. I wanted to show the faces of some of the people who carried out this horrific policy of forced assimilation of Indigenous children. Reed had been active out west during the time of Northwest Resistance and working for Indian Affairs, carried out a harsh policy of retribution. I also had a photo of the Kamloops IRS in the exhibition, a two-part image showing several hundred children lined up for a photo on the front lawn of the school. Now I wonder how many of those children are buried on the school grounds. We also had a section in the exhibition recognizing children who never returned home. The thousands of images I went through during my research, still haunts me to this day.

MARCOS GOMEZ

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

PATRICK MAHON

The news of the discovery of 215 graves of Indigenous children at the former residential school in Kamloops BC is tragic. As a Canadian from a settler colonial and churched background, I acknowledge with shame the truth about residential schools in Canada. I recognize the terrible suffering that would have occurred around those deaths, and will do, as this information becomes known among Indigenous people. I am truly sorry that such suffering occurred and continues due to colonialism and white supremacy.

The shame associated with residential schools for settler colonial people will remain a fact.

I accept this and I recognize there is work to do. Currently, I have the honour to work with Jeff Thomas on an exhibition related to the colonialism and the environment and Jeff has taught me that the work must go on. So I see part of my work involving the need to communicate with other people like me about the illusions we have regarding the kind of country this is. The news of the children buried at the residential school casts a light on the reality of our history, and speaks to the present regarding the effects of residential schools.

In order to live in the kind of country many often imagine we’re living in, there is real work for all of us to do to ensure truth, fairness, and economic justice for Indigenous people, and others who suffer the ongoing effects of colonialism.

Patrick Mahon, June 2, 2021

JENNA ROSE SANDS

JAYCE SALLOUM

Our hearts goes out to the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation and all Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island. As settler descendants we are complicit, if you are not working for change as part of your daily life/practice then you are sustaining the colonial system that continues this oppressive legacy.

This is a moment to reconsider what we are doing and to commit or re-commit to work to dismantle systematic racism in our country and the apartheid state we are living in – where the legal and policing forces have shown their deep rooted prejudices and inequities. The performative platitudes by government officials are meaningless, this is genocide and we are living its repercussions. As the uncovering of the atrocities of residential schools continues we have to keep asking, where is the accountability?

The federal government stopped recording the deaths of children at residential schools around 1920 after the chief medical officer at Indian Affairs suggested “children were dying at an alarming rate”. When will the perpetrators, churches, religious personal, and all levels of government officials be held accountable?

Kanada has known of these deaths for decades and done very little in concrete action to move towards restorative and criminal justice. This is not just in the past, today there are more Indigenous children taken into government custody than the 1960’s ‘60’s scoop’. The ‘justice’ system is weighted heavily against Indigenous people.

The incarceration rate for Indigenous women has risen more than 60% in the last 10 years. The rate of violent victimization among Indigenous people was more than double that of non-Indigenous people. Our government needs to stop spending millions of our dollars fighting the rights of Indigenous people, compensation and restitution are where the money should be spent. We have to ask, when will all the recommendations of the TRC and UNDRIP be taken seriously? We have to work towards concilliation, demand that our governments take concrete action on all TRC recommendations and UNDRIP ‘articles’.

Jayce Salloum, June 2, 2021

DAN SMOKE

Salaam... Sge:no My Friend.... Jamelie, how are you guys? We hope that you\re both healthy and happy....We hope that all the work that you are doing on the ECH is shared amongst everyone...... We are so busy right now, with such "heavy topics," that we have to take care of ourselves and do something. Before we would go to a sweat purification ceremony on a monthly basis, but COVID has taken care of that for well over a year now. We used to get together for Pipe ceremonies like we had with you and Marwan. We do go to a weekly "talking circle." that is good for us. It's all virtual. We do a lot of ZOOM presentations. We maintain a website with stories that revolve around Indigenous Mainstream, Alternative and sometimes Social News Media.

June 6, 2021

Sge:no and Salaam Jamelie.....("Peace" in the Seneca Language and your language.....)

Jamelie, you have my permission to use my posts to use however it can benefit ECH and the fact that the media is finally starting to be representative of Indigenous Issues and they are covering those stories and sending out balanced journalists to write them. (Including Indigenous Journalists, which is about time.....) The days of Christie Blatchford and Sara Milroy are numbered..... The public wants and deserves the truth. Back in the 90s and even into the new millennium, the public would come up to us and say, "How come they did not teach us that in school," and we replied, "That is because the corporate, municipal, provincial and federal Agenda don't want the public to know what happened 200 years ago, because it was "genocide" under the Geneva Convention....,." Canada is complicit... For example, the cross-Canada railroad was sent out west to be built. The workers were sent out, and they were not Native labourers, (who knew the territory...).. they were European ones. So, they slowly went westward as the railroad continued to be built and these camps were known as "man camps," which they still employ on the Trans Mountain Pipeline and other construction projects (today...). These "man camps" are the ones who are looking for entertainment and recreation and they see Indigenous women as the perfect form of fun and entertainment....So they are not accountable, or ethical.....They just exercise their hedonistic desires, they don't care what the result of their pleasure is. So, these construction projects are all about "man camps," and "ruination" of the Indigenous People. Just look at the "oilsands" projects" and the destruction left in their wake. Premier Kenney won't force the Corporations to clean up after themselves. A 200-year history that most Canadians do not even know about......

So, how do we access the "news stories" that represent "Indigenous Issues in a positive, truthful way???"

Our website and our public education manifesto is going to take off.......

Now, we can devote some time to get our radio show's "Archive" off the ground. We want to get all the cassettes digitized and available to the public.

Salaam Jamelie......Please express our deep gratitude to Ron, as well. He is like a brother to us.....We have to go out to dinner together when the restrictions of this lockdown get lifted. Today, Mary Lou and I got our second Pfizer vaccine at the Western Fair Agriplex.

June 7, 2021

TOM CULLI just want to add my expression of solidarity and deep sorrow. I am at a loss for words, so I will echo Jamelie, Joan, and Patrick's hopes/intentions for our GardenShip community to work together towards peace and justice while standing against settler colonialism, racism, and violence. |

JOAN GREERThe tragic suffering and death of these children brings shame to our country. With the terrible pain this knowledge brings, it further complicates and adds to the ongoing sufferings of many families and communities who remain close to these children and to this history. |

RESOURCES / READINGS:

Reality of residential schools was always there for us to see by Cindy Blackstock

At Western University: Biindigen Celebrates Indigenous History Month

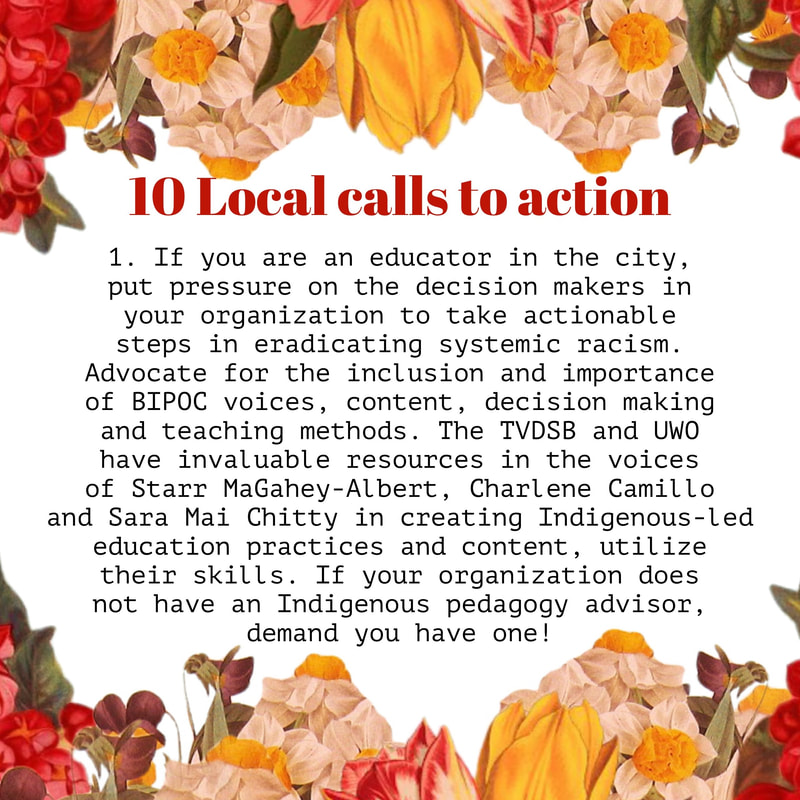

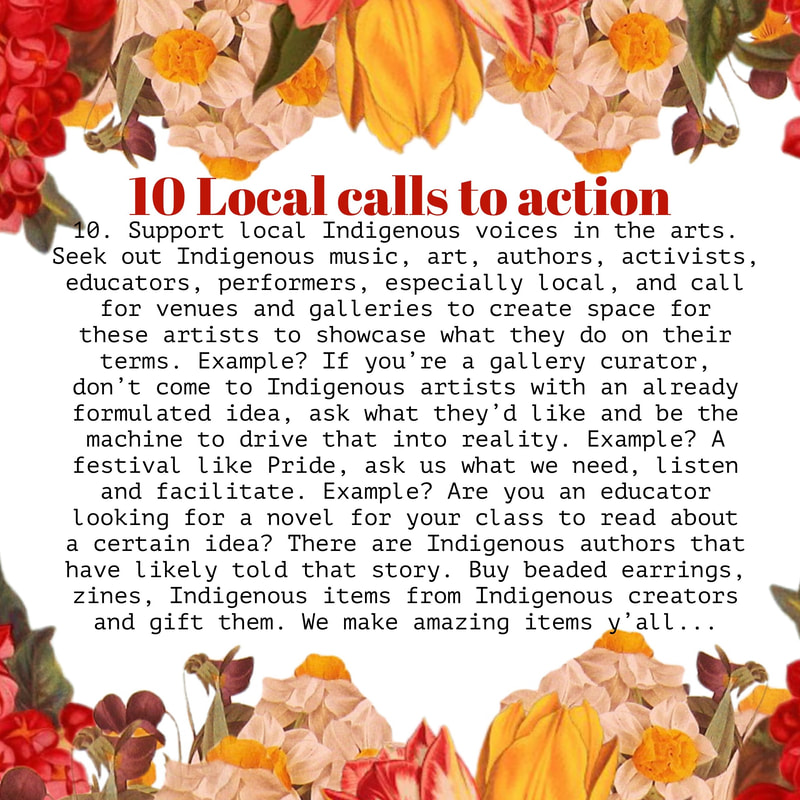

SETTLERS TAKE ACTION

Interview with lawyer Jean Teillet about the deep flaws in Canada’s ‘justice’ system and its systematic prejudice and process against Indigenous people.

National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is 1 step on a long journey, says Murray Sinclair

Southwestern Ont. First Nation investigating grounds of former residential school by Angela McInnes

Indigenous people need allies as we keep fighting for a seat at the table by Lisa Beaucage

Marlene Cloud, Area residential school survivor among Indigenous group meeting Pope by Calvi Leon

Reality of residential schools was always there for us to see by Cindy Blackstock

At Western University: Biindigen Celebrates Indigenous History Month

SETTLERS TAKE ACTION

Interview with lawyer Jean Teillet about the deep flaws in Canada’s ‘justice’ system and its systematic prejudice and process against Indigenous people.

National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is 1 step on a long journey, says Murray Sinclair

Southwestern Ont. First Nation investigating grounds of former residential school by Angela McInnes

Indigenous people need allies as we keep fighting for a seat at the table by Lisa Beaucage

Marlene Cloud, Area residential school survivor among Indigenous group meeting Pope by Calvi Leon