The Embassy Cultural House and the Old East Village

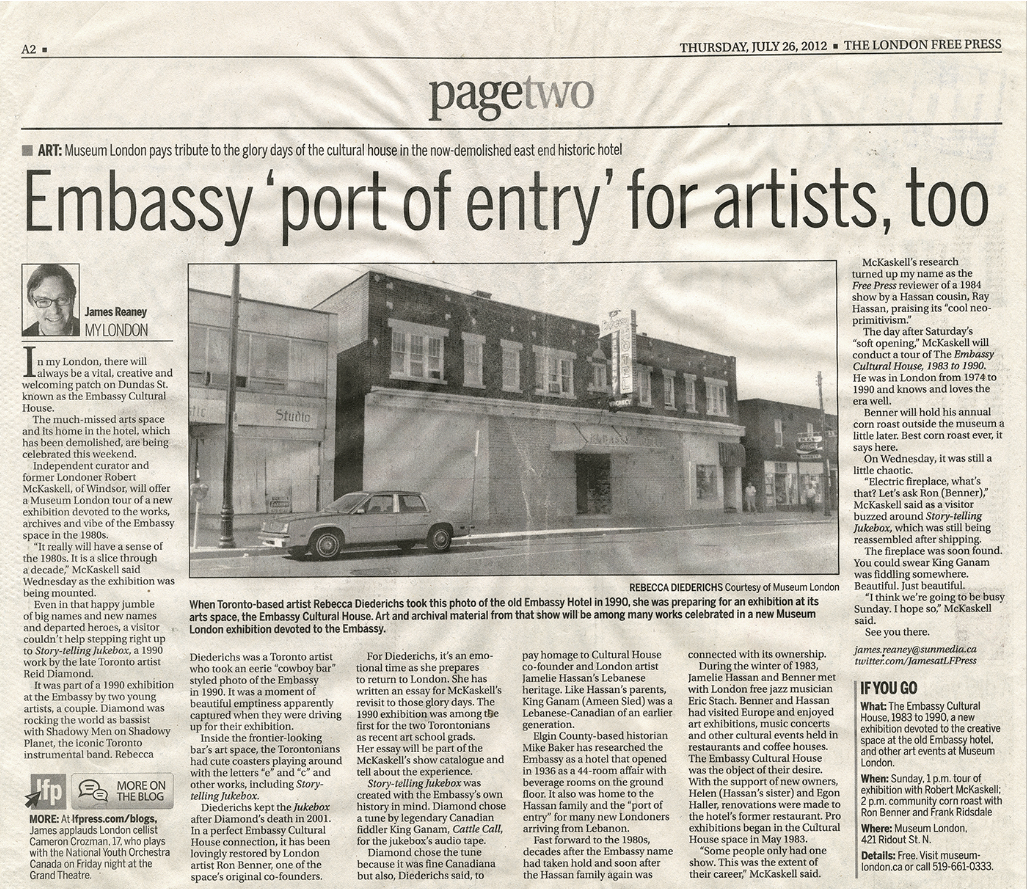

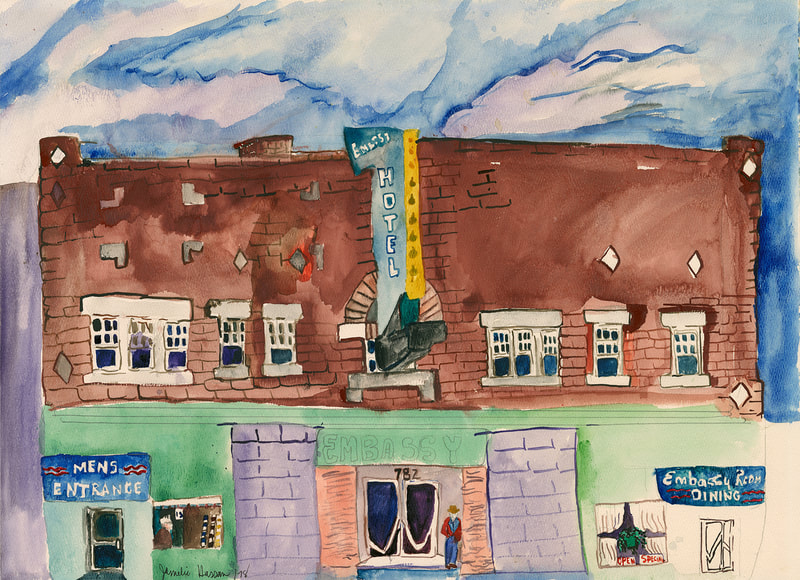

The ECH, an online community arts and cultural space, has physical roots and history in east London going back to its original founding as the Embassy Cultural House in 1983, formerly located in the old Embassy Hotel on Dundas St. |

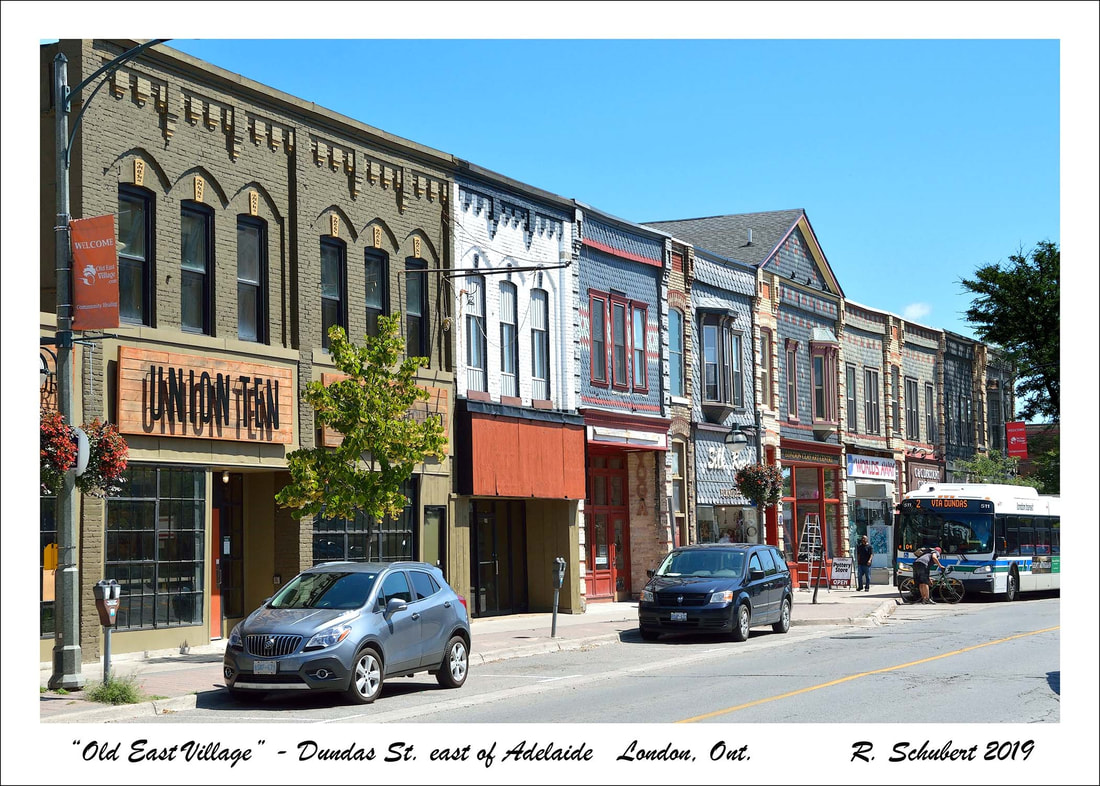

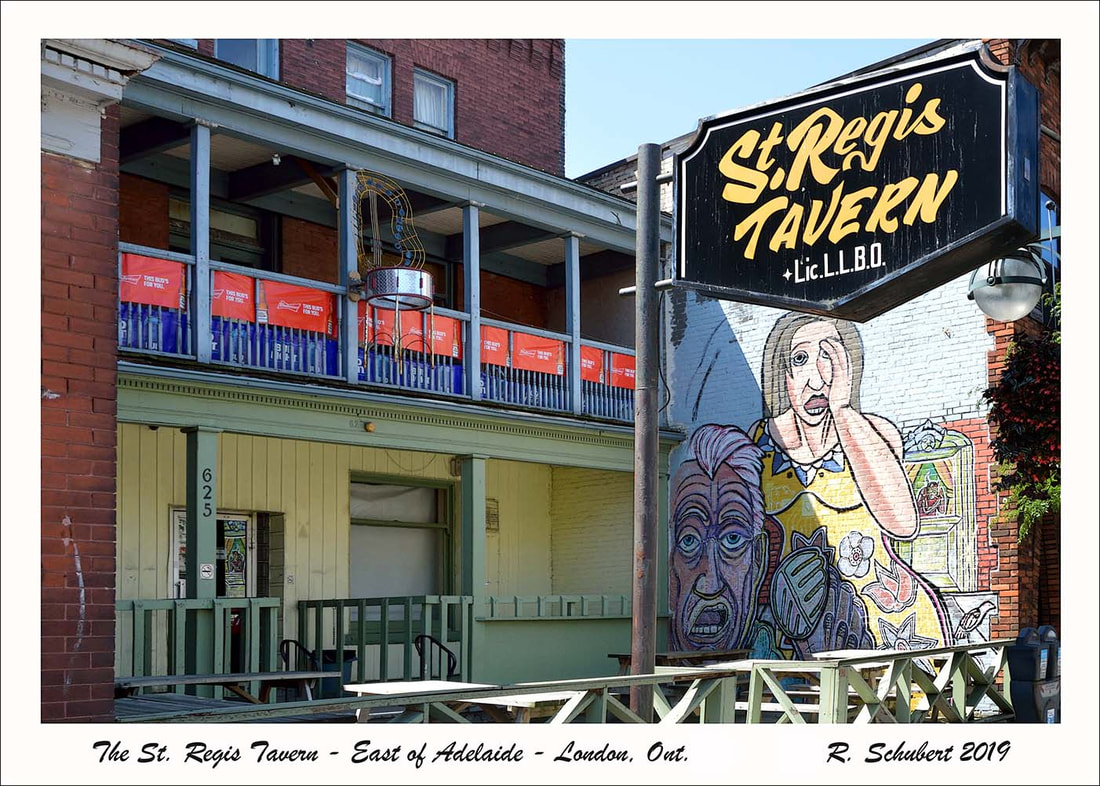

Photos of the Old East Village by Roland Schubert

The Embassy Cultural House was at the heart of the Old East Village located in the Old Embassy Hotel.

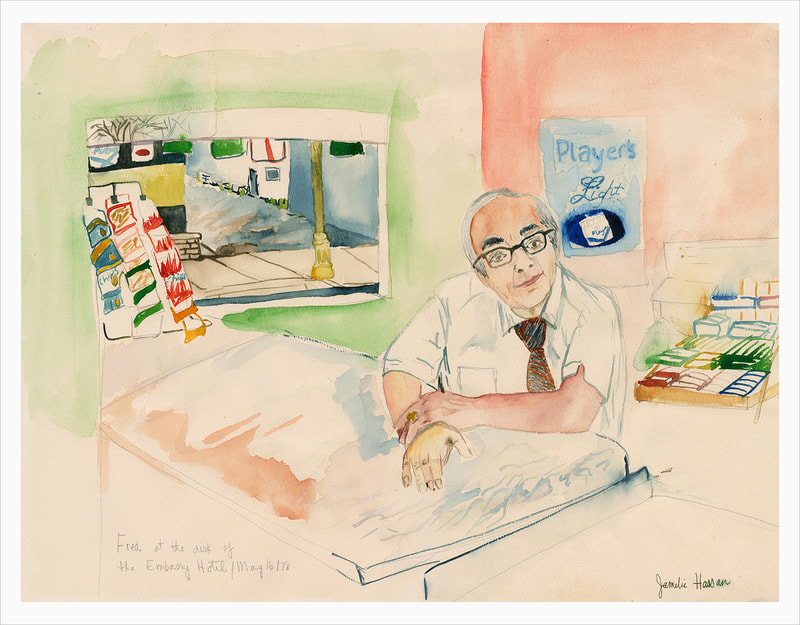

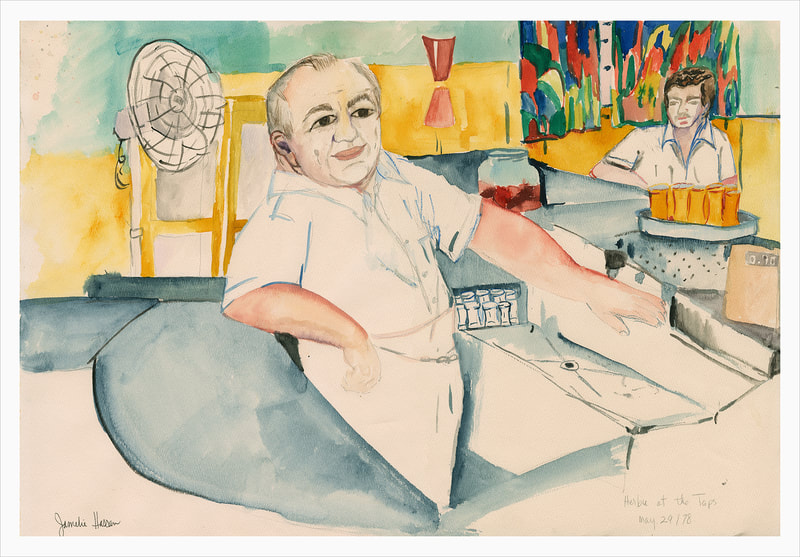

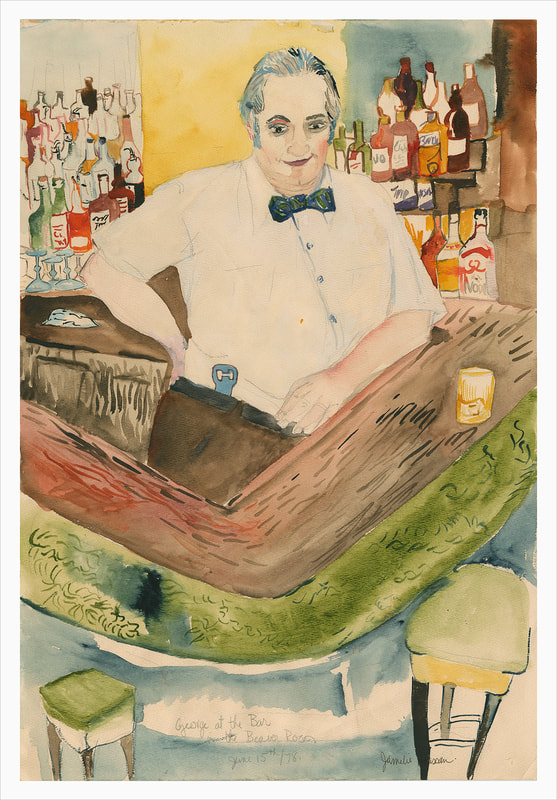

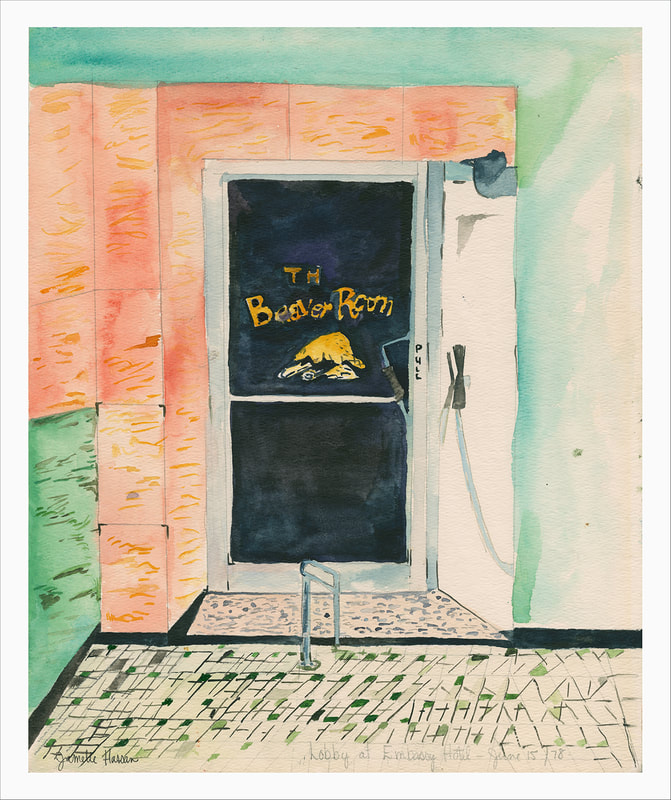

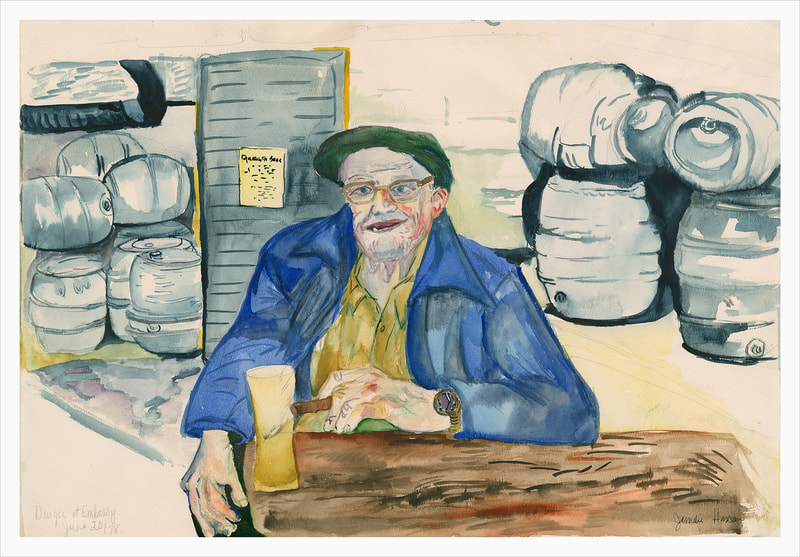

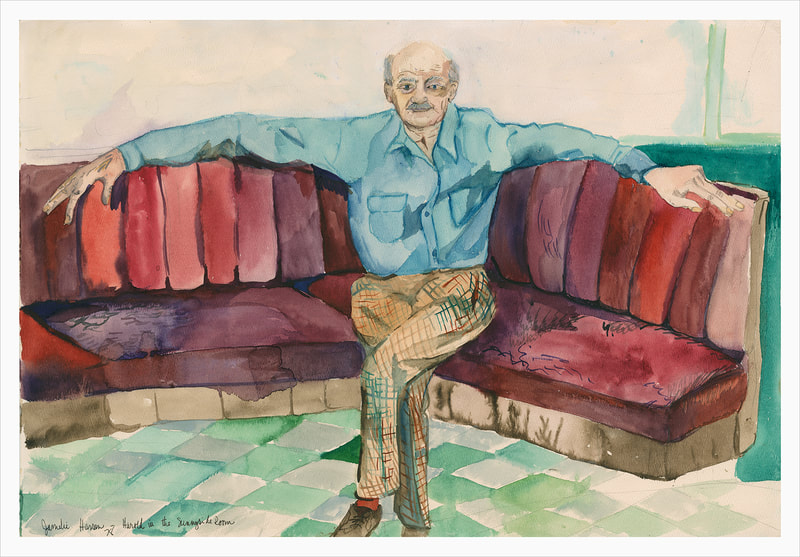

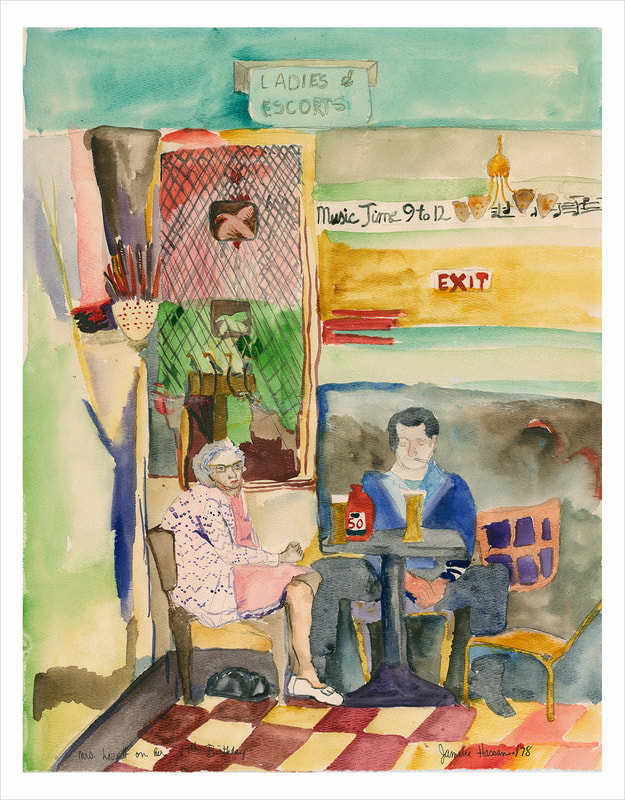

Watercolours by Jamelie Hassan in 1978 of the Embassy Hotel

These watercolours of the Embassy Hotel series of were donated to the Museum London's permanent collection by Helen Haller in 2019.

Embassy Hotel History by Melanie Townsend (1968 - 2018)

|

|

Historical information drawn from an essay by the late Melanie Townsend written for the catalogue of the Museum London exhibit, "The Embassy Cultural House 1983-1990 . The catalogue was published by Museum London in 2012. |

James Reaney: Hiding in Plain Sight with the King

Hamoody Hassan, London, on King Ganam via CBC.ca: |

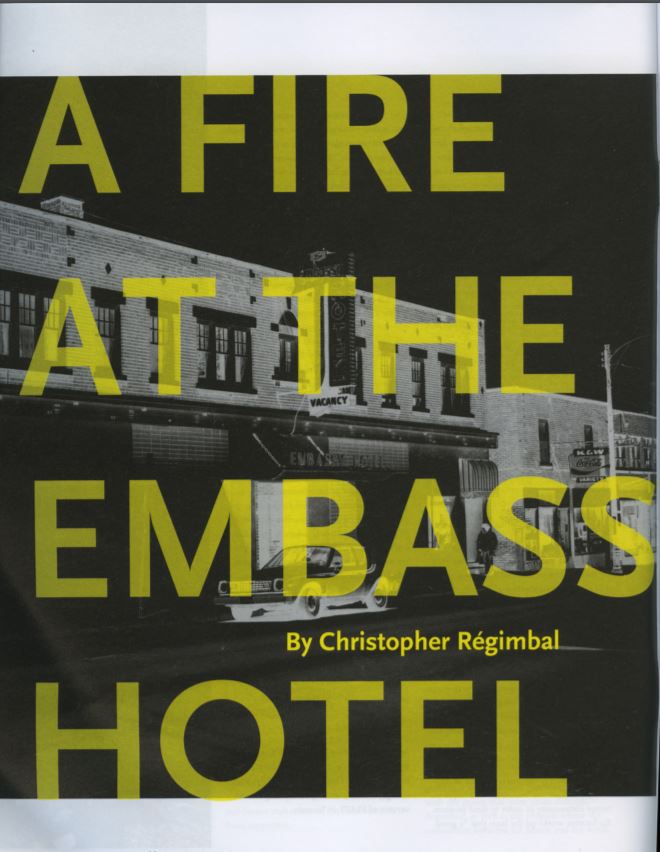

Reprint: Christopher Regimbal, "A Fire at the Embassy Hotel," Fuse Magazine vol. 33, no. 3, summer 2010

A big thank you to Christopher Régimbal, who provided us a scan of his article "A Fire at the Embassy Hotel," Fuse Magazine vol. 33, no. 3, summer 2010, 12-15. The article provides a great read of the Embassy Cultural House's history. A transcript of the article is below.

A FIRE AT THE EMBASSY HOTEL

By Christopher Régimbal

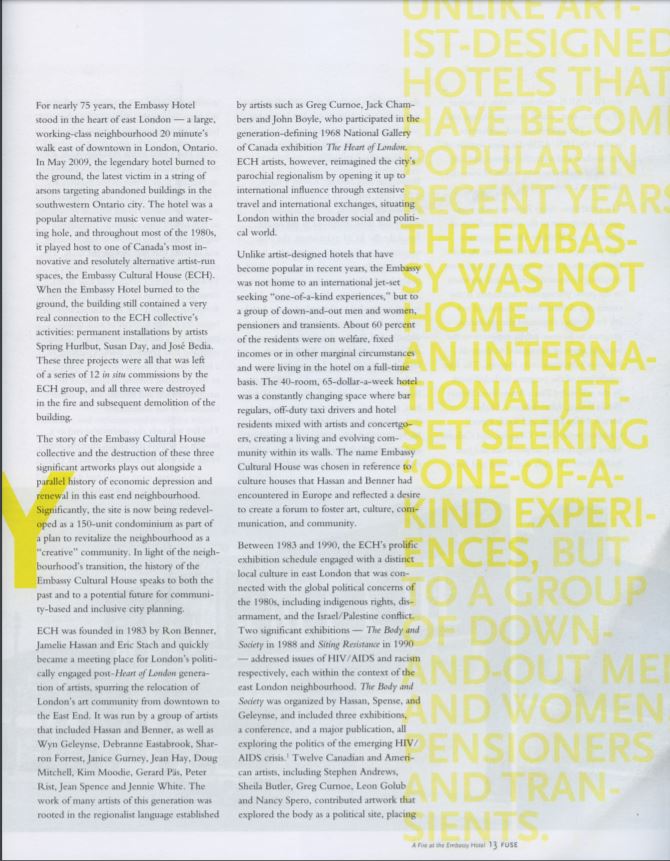

For nearly 75 years, the Embassy Hotel stood in the heart of East London – a large, working-class neighbourhood 20 minutes east of downtown in London, Ontario. In May 2009, the legendary hotel burned to the ground, the latest victim in a string of arsons targeting abandoned buildings in the southwestern Ontario city. The hotel was a popular alternative music venue and watering hole, and throughout most of the 1980s, it played host to one of Canada’s most innovative and resolutely alternative artist-run spaces, the Embassy Cultural House (ECH). When the Embassy Hotel burned to the ground, the building still contained a very real connection to the ECH collective’s activities: permanent installations by artists Spring Hurlbut, Susan Day, and José Bedia. These three projects were all that was left of a series of 12 in situ commissions by the ECH group, and all three were destroyed in the fire and subsequent demolition of the building.

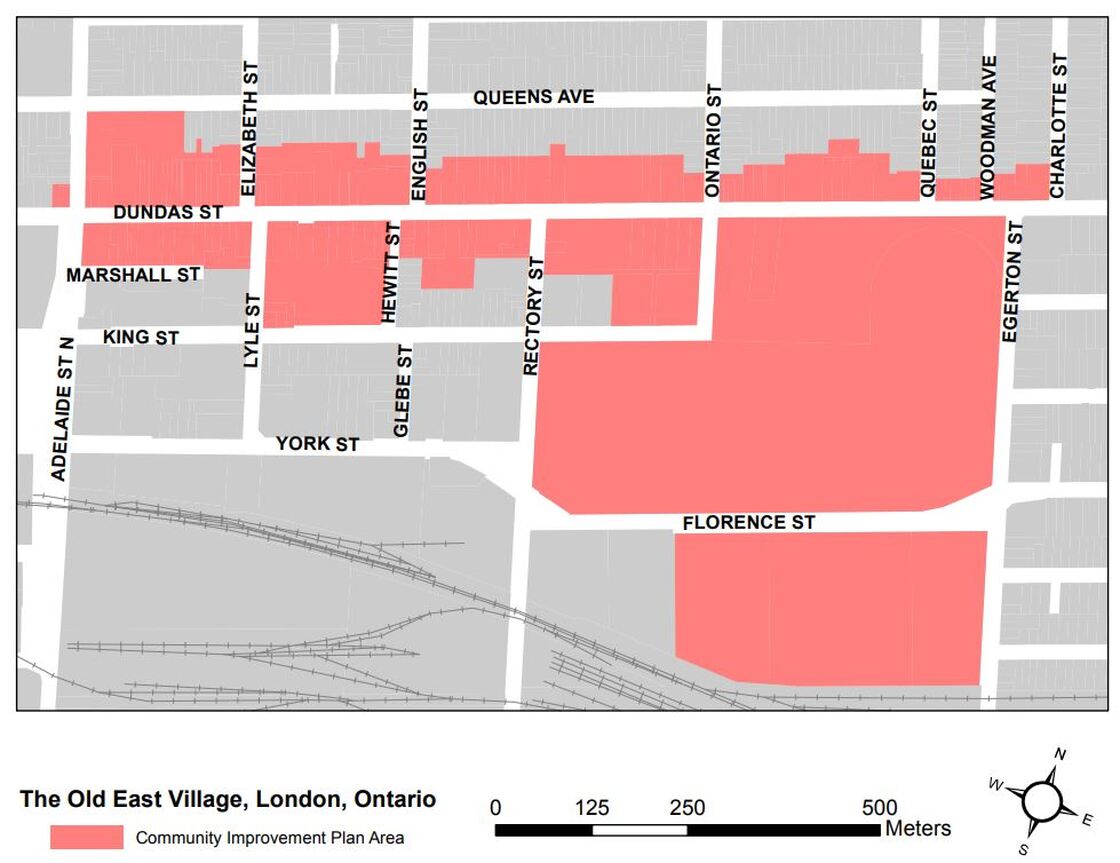

The story of the Embassy Cultural House collective and the destruction of these three significant artworks plays out alongside a parallel history of economic depression and renewal in the East End neighbourhood. Significantly, the site is now being redeveloped as a 150-unit condominium as part of a plan to revitalize the neighbourhood as a “creative” community. In light of the neighbourhood’s transition, the history of Embassy Cultural House speaks to both the past and a potential future for community-based and inclusive city planning.

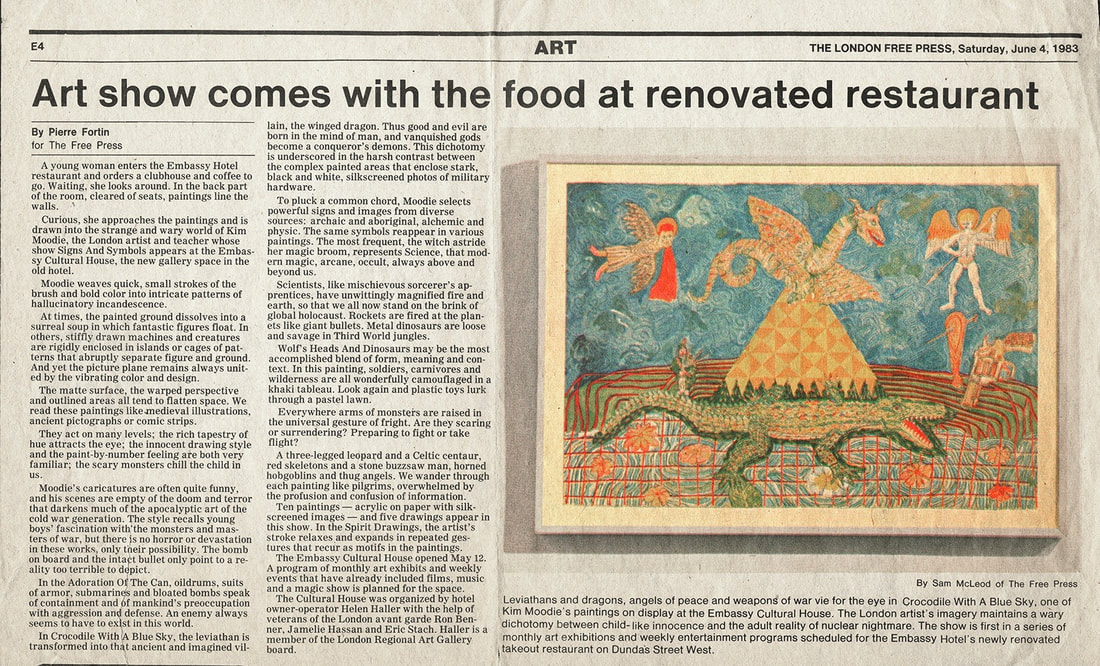

ECH was founded in 1983 by Ron Benner, Jamelie Hassan and Eric Stach and quickly became a meeting place for London’s politically engaged post-Heart of London generation of artists, spurring the relocation of London’s art community from downtown to the East End. It was run by a group of artists that included Hassan and Benner, as well as Wyn Geleynse, Debrann Eastabrook, Sharron Forrest, Janice Gurney, Jean Hay, Doug Mitchell, Kim Moodie, Gerard Päs, Peter Rist, Jean Spence and Jennie White. The work of many artists of this generation was rooted in the regionalist language established by artists such as Greg Curnoe, Jack Chambers and John Boyle who participated in the generation defining 1968 National Gallery of Canada exhibition The Heart of London. ECH artists, however, re-imagined the city’s parochial regionalism by opening it up to international influence through extensive travel and international exchanges, situating London within the broader social and political world.

Unlike artist-designed hotels that have become popular in recent years, the Embassy was not home to an international jet-set, seeking “one-of-a-kind experiences” but to a group of down and out men and women, pensioners and transients. About 60 percent of the residents were on welfare, fixed incomes or in other marginal circumstances and were living in the hotel on a full-time basis. The 40-room, 65-dollar-a-week hotel was a constantly changing space where bar regulars, off-duty taxi drivers, and hotel residents mixed with artists and concertgoers, creating a living and evolving community within its walls. The name Embassy Cultural House was chosen in reference to culture houses that Hassan and Benner had encountered in Europe and reflected a desire to create a forum to foster art, culture, communication, and community.

Between 1983 and 1990, the ECH’s prolific exhibition schedule engaged with a distinct local culture in East London that was connected with the global political concerns of the 1980s, including indigenous rights, disarmament, and the Israel/Palestinian conflict. In two significant exhibitions The Body & Society in 1988 and Siting Resistance in 1990 addressed issues of HIV/AIDS and racism respectively, each within a context of the East London neighbourhood. The Body and Society was organized by Hassan, Spence, and Geleynse and included three exhibitions, a conference, and a major publication, all exploring the politics of the emerging HIV/AIDS crisis. Twelve Canadian and American artists, including Stephen Andrews, Sheila Butler, Greg Curnoe, Leon Golub and Nancy Spero, contributed artwork that explored the body as a political site, placing the HIV/AIDS epidemic within a context of gender, race, sexual orientation, age and income. The exhibition and conference pushed the HIV/AIDS discourse outside of the medical and scientific spheres and into the social and economic realms of everyday life in East London.

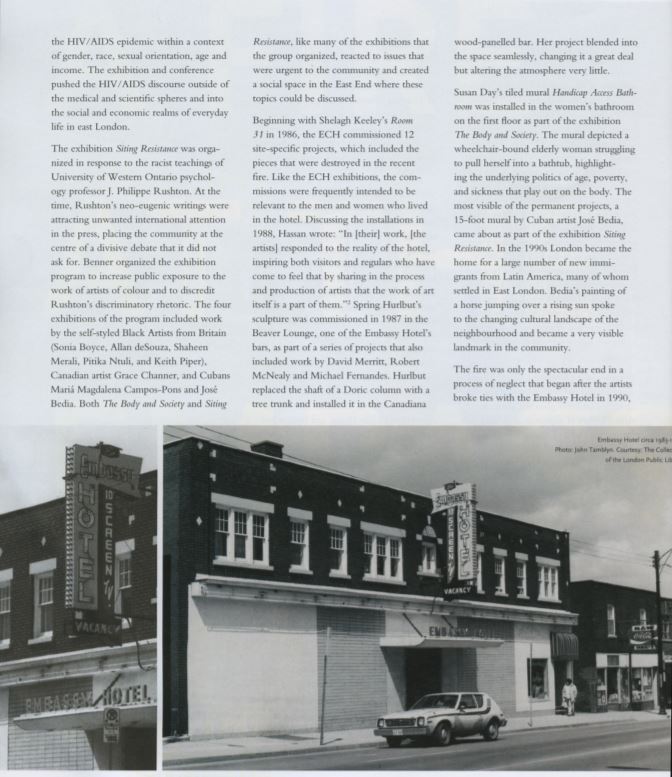

The exhibition Siting Resistance was organized in response to the racist teachings of University of Western Ontario psychology professor J. Philippe Rushton. At the time, Rushton’s neo-eugenic writings were attracting unwanted international attention in the press, placing the community at the centre of a devisive debate that it did not ask for. Benner organized the exhibition program to increase public exposure to the work of artists of colour and to discredit Rushton’s discriminatory rhetoric. The four exhibitions of the program included work by the self-styled Black Artists from Britain including Sonia Boyce, Allan de Souza, Shaheen Merali, Pitika Ntuli, and Keith Piper, Canadian artist Grace Channer, and Cubans Mariá Magdalena Campos and José Bedia. Both The Body & Society and Siting Resistance, like many of the exhibitions that the group organized, reacted to issues that were prescient to the community and created a social space in the East End where these topics could be discussed.

Beginning with Room 31 by Shelagh Keeley in 1986, the ECH commissioned 12 site-specific projects, which included the pieces that were destroyed in the recent fire. Like the ECH exhibitions, the commissions were frequently intended to be relevant to the men and women who lived in the hotel. Discussing the installations in 1988, Hassan wrote: “In [their] work, [the artists] responded to the reality of the hotel, inspiring both visitors and regulars who have come to feel that by sharing in the process and production of artists that the work of art itself is a part of them.” Spring Hurlbut’s sculpture was commissioned in 1987 in the Beaver Lounge, one of the Embassy Hotel’s bars, as part of a series of projects that also included David Merritt, Robert McNealy, and Michael Fernandes. Hurlbut replaced the shaft of a Doric column with a tree trunk and installed it in the Canadiana wood panelled bar. Her project blended into the space seamlessly, changing it great deal but altering the atmosphere very little.

Susan Day’s tiled mural Handicap Access Bathroom was installed in the women’s bathroom on the first-floor as part of the exhibition The Body & Society. The mural depicted a wheelchair-bound elderly woman struggling to pull herself into a bathtub, highlighting the underlying politics of age, poverty, and sickness that play out on the body. The most visible of the permanent projects, a 15-foot mural by Cuban artists José Bedia, came about as part of the exhibition Siting Resistance. In the 1990s, London became the home of a large number of new immigrants from Latin America, many of who settled in East London. Bedia’s painting of a horse jumping over a rising sun spoke to the changing cultural landscape of the East End neighbourhood and became a very visible landmark in the community.

The fire was only the spectacular end in a process of neglect that began after the artists broke ties with the Embassy Hotel in 1990, at which time nothing was left of the collective as an entity able to offer stewardship over the site-specific artworks remaining in the hotel. Over the years, the rest of the 12 permanent installations went missing or were destroyed, including projects by Lani Maestro, Elizabeth MacKenzie, Robert McKaskell and Liz Magor. After the hotel was sold but before the sudden fire, Museum London Director, Brian Meehan, was working with the real estate developer to assess the possibility of salvaging some of the remaining artwork into a public collection. After the fire but before the building was demolished, the artistic community implored the city to save the José Bedia mural, which was not damaged in the fire, but extensive structural damage to the remainder of the hotel led to the demolition of the building within a matter of days.

Ironically, since London was an important centre for contemporary art, poetry, literature, and experimental music for many years, the City of London has begun a top-down effort to re-brand itself as a Richard Florida-inspired “creative city.” The East End, which had largely been ignored by developers until recently, has become a very attractive site for gentrification. What sets the Embassy Hotel apart from other, more recent artistic hotel projects is that instead of facilitating gentrification, the ECH helped the neighbourhood resist it. In the 1980s, rapid development in London’s downtown drove up property prices in the core while neglect and absentee landlords helped to keep prices in East London low. Speaking at the Dia Art Foundation in 1989, Hassan prophetically raised the spectre of development in the East End saying: “I don’t know if in 15 years …[we] will also fall pray to developers. That may very well be the case. But we are strongly encouraging anyone who has any resources to work together with us cooperatively and collectively.” ECH artists often worked as advocates for the disenfranchised communities in the area, participating in a coalition of residents to protect heritage sites and prevent crippling development.

Between the time the Embassy Cultural House closed and the present day there has been very little investment in East London, and many of the buildings are now in disrepair, boarded up, or, like the Embassy Hotel, burned out. The condominium development on the site of the former Embassy Hotel is the first major residential development in the neighbourhood, signaling a new and irreversible shift in the community dynamic. Twenty years after Hassan made her prediction of development, this new condo project will undoubtedly change the makeup of the East End, and, after years without investment into the community, change is sorely needed. The artists of the Embassy Cultural House showed us that by working with the community, even if only with modest means, you could create inclusive and productive change. My hope is that those who call for the revitalization of London’s East End keep this lesson in mind.

Christopher Régimbal is an art historian and curator originally from Timmins, Ontario. He has written for Art Papers and Magenta Magazine and is currently the Curatorial Assistant at the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery at the University of Toronto.

Prepared with files from the archives of Ron Benner and Jamelie Hassan, the Embassy Cultural House archives at the London Public Library, and with the help of Joe Belanger at the London Free Press.

Update: October, 27, 2020 - The condominum project for the site of the former Embassy Hotel was not realized and the location remained a vacant lot for a number of years. Indwell, a not for profit organization was able to acquire the land and an affordable housing project is now under construction. The affordable housing project will carry the name Embassy Commons in recognition of the cultural work that previously was hosted at the Embassy Hotel and Embassy Cultural House.

The author of this essay, Christopher Régimbal is now senior exhibitions manager at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.